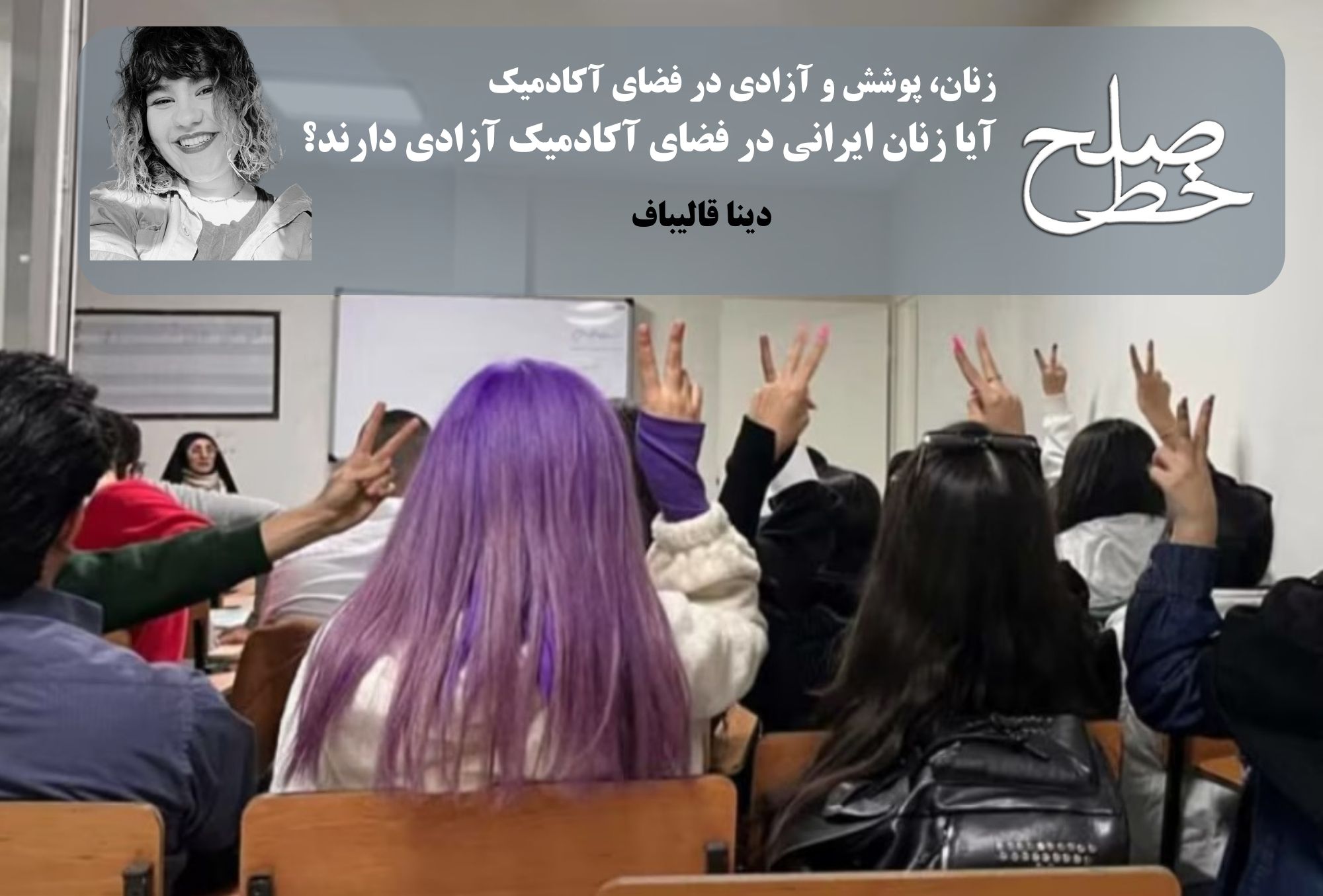

Do Iranian women have freedom in academic spaces? / Dina Ghaleibaf

In Iran, all students sign a commitment when registering at university, stating that after passing the entrance exam, this commitment signature is considered a crucial requirement for entering university or academic spaces. If a student resists signing this commitment, they will not be allowed to register at the university.

In the text that students sign, they commit to following all university regulations, which are specified in the disciplinary code approved by the Ministry of Science. One of these regulations pertains to adhering to appropriate dress according to Islamic laws, which the university expects both male and female students to abide by on campus. Prior to the protests following the death of Mahsa Amini in universities, students often faced humorous encounters with security guards at the entrance regarding their dress and hijab. If they were denied entry due to inappropriate dress, they would go to another entrance and eventually be able to enter the university. However, with the start of the protests, there was neither student confrontation regarding the issue of hijab, nor any action taken by security guards or disciplinary committees. It can be said that after the beginning of a new chapter for Iranian women with the death of Geena, the perspective of female students towards the hijab law changed and they no longer saw it only as a law they were obligated to follow

Following these intellectual changes, the university used its two arms of power, namely the security and disciplinary committee, to suppress protesting students against mandatory hijab and took practical measures to force them to comply with Islamic dress code. In one case at Shahid Beheshti University (National), female students were banned from registering for courses on the day of course selection and the opening of the system for them was conditional upon signing commitment forms to adhere to appropriate dress code at the university level. In addition, internal monitoring teams were deployed in most universities and students who did not comply with hijab were identified and summoned by security personnel to the disciplinary committee. The measures became so severe that even professors were pressured not to give exams to students who did not wear hijab during final exams. These actions, which have caused turmoil in the academic environment, especially for women, and sometimes marginalize their rights and privileges in this space, raise a fundamental question: Do Iranian women have freedom in the academic environment?

A student’s account of sexual assault on campus.

The question that was raised above was discussed among several students from different universities in Tehran, resulting in accounts of a turbulent atmosphere for women in the academic environment, entangled with various issues ranging from lack of gender diversity to sexual harassment.

In this regard, a female student who is studying for her Bachelor’s degree at Sohank University, recounts a sexual assault by one of the security guards: “In our university, the entrances for men and women are separate and about two weeks ago, I was sexually assaulted in front of the women’s entrance. I have a knee-length coat that I used to wear a lot at the university because it was cool and I also used it last year. This year, I wore the same coat but they stopped me at the entrance and took a commitment from me.”

He says it has happened many times before that they have tried to get a commitment from him, but because he resisted, they did not let him into the university: “I do everything I can because of my family circumstances not to get involved with the disciplinary committee. Many times they have told me that my clothes are not good and I have to make a commitment to be able to enter, and I said I won’t make a commitment, but that day I couldn’t even enter the university.”

This student, on the day she was sexually assaulted, made an exception to enter the university: “After I made the commitment to be able to enter the university, there were a few male security guards standing in front of the women’s dormitory, one of them grabbed me and said, ‘What are you wearing?’

I was very disturbed at that moment and asked myself, what did this person do? It took me a while to analyze the situation. I reported the incident to my department manager that day. The next day, I filed a written complaint with the dean’s office, but I doubt anything will happen. When this happened on Saturday, I filed my complaint on Monday and on Tuesday, I saw that person in front of the door again! Even on Saturdays, I saw that person in front of the university’s cafeteria.”

Academic space and the absence of gender diversity.

A female student who is studying for her master’s degree in political science at Tehran University believes that academic rights for women are not limited to freedom in dress: “In the Faculty of Law and Political Science at Tehran University, and especially in the field of political science, female professors are not accepted. The women who are there do not have any activity in academia and the male-dominated system has not changed.”

He continues his narrative, saying: “From the very first glance, it is clear how you think and essentially why they should judge you, even if you have no problems and it is simply evident from your appearance which group or thoughts you belong to. To some extent, we may think that this is not the most disturbing aspect, because the university has an internal suppression and a system within itself. In addition to obvious violence, the university engages in the production and reproduction of symbolic violence every day, through any mechanism you can think of. For example, in the form of not having female faculty members, which silences many voices. There is no gender diversity, which is very influential. Equality in academia is not defined solely by equality in appearance, but there is a symbolic violence under the skin of the university. When you step out of the university, another system is being produced, which is difficult to escape within the university.”

He adds, “The spaces within the democratic university are very limited and only exist in special moments. In my opinion, we are dealing with an order that is not heavy or fragile, but appears very heavy. That is, the university is managing everything, but at the same time it is slipping, giving agency to us students. For example, a small action from you can disrupt this heavy order for two hours, and it is interesting that there is an agency. It may not have a big impact that you can walk through the university with a short coat, but it creates a personal feeling that you tell yourself, ‘I also have power.’ Maybe this is not important for the individual, but behind the scenes, I think it is interesting even if it is a mischievous act. An interesting experience for me regarding dress and the behavior of the security guards is that they do not follow any specific rules, but their behavior is based on their own will. This desire to control – that the

Compulsory hijab, an obstacle for women’s educational activities.

Mahshid Ahmadi is a student of industrial engineering at Khaje Nasir University. Recently, she was forced to participate in a working group titled “Chastity and Hijab.” She describes the pressures that the university’s security has imposed on female students regarding the issue of hijab: “After the change of university presidency and security, we came under heavy pressure. Not only female students, but also males were forced to commit to wearing a necklace and shaking hands with girls under the supervision of security. I entered the university during the events of 1401, but at that time the issue of clothing was not so prominent. However, from April 1402, the strictness became so great that we could no longer enter the university with the clothes we used to wear, and they even checked if the buttons were open or closed.”

He adds, “In October 2023, we were required to obtain an electronic signature from us in the Golestan system for course selection, which included regulations such as girls’ mantos (clothing) must be below the knee. Until we confirmed these conditions, the Golestan system did not allow us to choose our courses. After this incident, the pressure from the security increased in various ways, and it was even more intense in the Vanak campus.”

This student narrates the continuation of the story of the conflict between the security guards and one of the female students: “In one of the campuses, the security guards harassed a female student for wearing a short coat, and those who tried to defend her were also punished and some even received suspension orders. If a woman’s clothing is even slightly above the knee, they will confront her. Another repressive action of the university regarding the issue of hijab was sending text messages to 95% of female students. When the text message story started a year ago, it was written that if the message is sent three times, students must go to the committee.”

He continues: “In recent months, after it was planned to hold elections for student activities such as scientific associations and guild councils, many girls were disqualified because of these text messages. In Vanak campus, we didn’t even have a female candidate, because their qualifications were rejected by the security. A student may have bigger concerns, but the university has implemented policies that force me, as a student, to think about whether my outfit today will allow me to enter the university or not.”

This student concludes by saying, “These incidents even put pressure on the professors. For example, recently the university’s head of security forced me to participate in the Modesty and Hijab Committee with the presence of a representative from the Supreme Leader’s office, and they asked me to sign papers and commit to respecting the university’s standards regarding clothing. I wasn’t treated badly there, but I could tell from my professors’ eyes that they were forced to participate in this committee just to prevent students from becoming too active and passionate.”

The accounts of students about the university’s treatment of their attire, alongside videos and testimonies showing the violent treatment of women by police in the streets, indicate that the issue of hijab has become the most politicized after the events that took place in society with the killing of Mahsa Amini. Today, it has become the most political issue, and any resistance against it will lead to a suppressive and punitive treatment of women, both in academic spaces and in society.

Tags

"Female students" Academic space Compulsory hijab Dina Ghaleibaf Gender discrimination 2 Mahsa Amini Monthly Peace Line Magazine peace line Peace Treaty 158 Trade council University security Unveiling Unveiling/Uncovering/Removal of the Hijab Woman, freedom of life