During the external bombardment, internal censorship and women in the forefront of the narrative / Elaheh Amani

“In war, women and children are the first victims, even before the conflicts begin seriously.”.*

War is gendered, not neutral. The wounds of war are not only on bodies, but also in lives that are forever changed, and it is women who carry these wounds silently. The costs and consequences of war disproportionately burden women and girls, and it transforms their lives in ways beyond the battlefield. According to the United Nations, over 600 million women and girls are currently affected by war, a staggering number that has increased by nearly 50% in the past decade. These conflicts are not abstract phenomena, but they manifest in destroyed homes, broken families, and unstable communities. (1) In 2023 alone, the percentage of women killed in armed conflicts has doubled from the previous year, and sexual violence related to conflicts has increased by 50%. (2) These numbers are more than just statistics, they represent destroyed lives and shattered dreams. Despite extensive evidence and international efforts to support women affected by war, militaristic regimes that perpetuate these cycles of violence continue to ignore gender considerations

This article explores the gendered impacts of war, from physical and psychological harm to the social and economic marginalization of women, the role of women in establishing sustainable peace, and the role of female journalists in reporting on narratives that are often sensitive to gender and sexuality.

The impact of war on women and girls.

War and military conflicts turn the daily lives of women into a constant struggle for survival. For women and girls, this struggle becomes even more complex and layered, relying on gender roles, unequal power dynamics, and patriarchal attitudes. Wars and military attacks destroy infrastructure and create a chain of health, education, and economic crises that disproportionately affect women. The displacement caused by war forces millions of women and girls to flee their homes and leave their lives behind. Refugee camps and temporary shelters are often lacking in basic safety measures, leaving women vulnerable to exploitation and sexual violence. According to the United Nations, women make up a large portion of the refugee population in conflict zones. Many are separated from their families and suddenly find themselves responsible for caring for children and elderly relatives with minimal resources. In many countries facing military conflicts, women play a crucial role in subsistence agriculture and the informal economy. War destroys these fragile systems and plunges families into poverty. The economic vulnerability of women can lead them to make risky and unhealthy

Education of girls is one of the first and most widespread casualties of war. Attacks on schools and insecurity and displacement force girls out of classrooms and towards early marriages. In the coastal region of Africa, military tensions have significantly increased rates of forced child marriages and girls dropping out of school. Perhaps the most horrific aspect of war for women is the deliberate use of sexual violence as a weapon. Sexual violence during war is neither accidental nor inevitable, but a calculated military strategy to instill fear, terror, and exert control. From conflicts in Sierra Leone to Bangladesh, sexual violence has been used on a large scale. During the civil war in Sierra Leone, it is estimated that 215,000 to 257,000 women and girls were raped, often in group attacks or through forced marriages. In the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, Pakistani forces systematically raped between 200,000 to 400,000 women. These acts of violence are not only meant to humiliate the victims, but also to

Sexual violence during war is not accidental, but rather systematic and designed to achieve military, political, or economic goals. War and military conflicts destroy healthcare systems and cut off or minimize access to essential maternal care and sexual and reproductive health services. The World Health Organization estimates that in conflict zones, every two hours, a woman or girl dies due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth. (4) Lack of access to contraception also leads to unintended pregnancies, and survivors of sexual violence face challenges in seeking care and treatment for the trauma they have experienced. Hunger also has a gender dimension, with almost 60% of those experiencing severe food insecurity in the world being women and girls, especially in countries affected by war. (2) When food becomes scarce, women often eat last and the least, prioritizing their children and male family members, a silent sacrifice rarely reflected in the news. Women who are forcibly displaced as part of armed forces also face immense barriers to healthy and fertile relationships within the social fabric.

The psychological wounds of war on women remain long after the signing of the ceasefire. Women who experience sexual violence struggle with issues such as depression and anxiety, often without access to mental health services. Cultural stigma surrounding assault exacerbates these wounds and silences women, leading to social isolation. War can also disrupt traditional gender roles. Experience shows that during war, women become the main breadwinners, but after the war they are pushed back into traditional roles. This phenomenon highlights the fragility of progress towards gender equality in different societies.

While women make up half of society and witness the heavy toll of war, they play a vital role in creating peace. The adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 in 2000 was a turning point in recognizing the impact of war on women and the crucial role of women in peace processes. (6) According to UN research, the presence of women can have a significant impact on the sustainability of peace agreements, although currently this process is slow and insignificant. In 2023, only 9.6% of women were present at the negotiating table for peace talks. (2) Evidence shows that peace agreements negotiated with the participation of women are 35% more likely to last for 15 years or more. The reality is that women reflect the needs and demands of society in the formulation of peace agreements, emphasize social cohesion, and prioritize them. In Yemen, women negotiators were able to secure agreements for safe drinking water access for civilians. In Sudan, nearly 50 women’s

Activists and peace advocates like Julienne Lusenge, a defender of women’s rights in the Democratic Republic of Congo, are shining examples of resilience. Having witnessed the horrors of war, she now leads efforts to support survivors of sexual and gender-based violence and emphasizes that women hold the key to peace. Feminist researcher Ursula Franklin rightly points out, “War is not even good for warriors.” Her words serve as a reminder that militarism is a broken and ineffective system that must be replaced with diplomacy, justice, and gender equality.

The effects of displacement and sexual violence during war are undeniable, as women and girls who are forced to flee their homes and communities are left hungry and exposed to sexual violence and psychological harm on a scale beyond imagination. However, women are not just victims, they are also agents of change and architects of peace. Sustainable peace cannot be achieved without the active participation of women at the negotiating table and recognition of their key role. As Ruth Morgan said nearly a century ago, “the responsibility for creating peace lies with every woman in this room,” and today this responsibility has extended beyond the confines of the room and reached the borders. This responsibility calls upon us to challenge the warmongering of those in power who beat the drums of war and perpetuate violence, and to emphasize a gendered approach in establishing peace and ensure that social justice and gender equality are not only achieved in the absence of war.

The 12-day war and its effects on women and girls: War takes a toll on the bodies and lives of women.

In late spring of 1404, tensions between Iran and Israel quickly escalated and turned into a widespread military confrontation. But behind the statistics and numbers, the real faces of the victims were the most heartbreaking: women and girls whose lives changed irreparably in a matter of days. Iran’s missile attacks on Israel left at least 28 dead and over 3000 injured, some of whom were civilians. In addition, Israel’s airstrikes on Iran resulted in over 1190 deaths and 4475 injuries. (6).

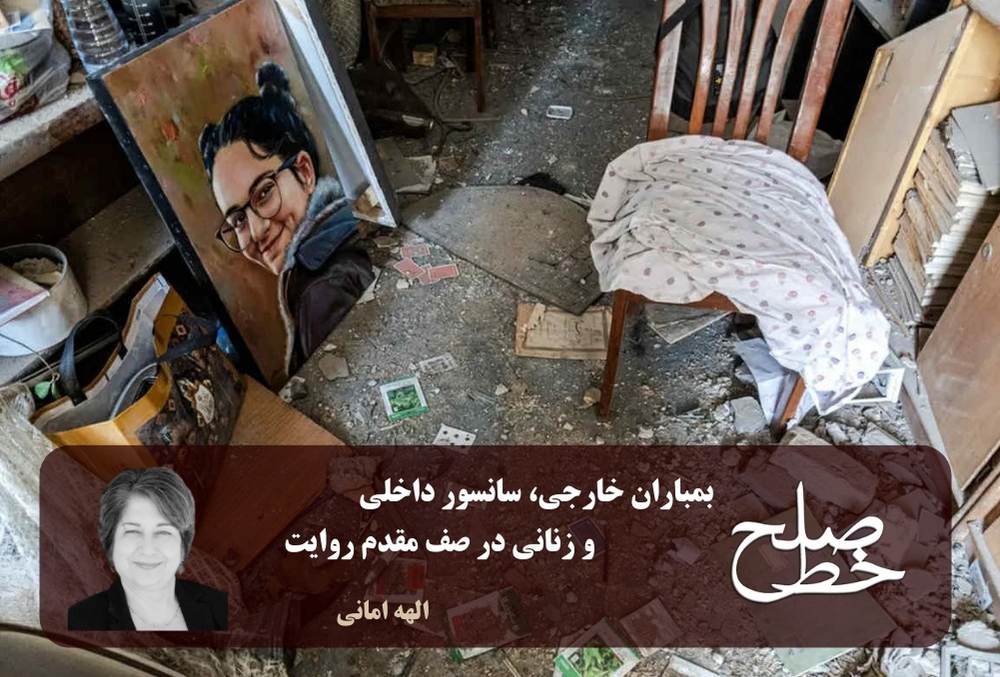

In many wars, the media only focus on the geopolitical aspects, but in the difficult days of the twelve-day war, under one-dimensional news, a generation of fearless reporters – many of them women – resisted with determination against foreign bombardment and internal censorship and presented true narratives that will remain in the historical memory of the Iranian people. Yes, wars are always narrated with casualty statistics, military power, and geopolitical analysis, but the truth of war is imprinted on human bodies, especially the bodies of women and girls. When the first missiles landed on cities, the sound of terrified children, the anxiety of pregnant mothers, and the trembling hands of women searching for their loved ones among the rubble were the beginning of a narrative that did not appear in any official report, not in Palestine, not in Ukraine, and not in the twelve-day war in Iran.

The reality of war is not just the destruction of homes, but also the violation of bodily privacy, loss of security, displacement, and heavy burden of caring for families for women. In the midst of every war, women’s bodies become scenes of intersection between violence and survival, where military violence merges with gender discrimination and turns women into both “targets” and “guardians of life” (7 and 8). In such circumstances, the voice of women journalists is not only reporting the truth, but also resistance against forgetting. During the 12-day war between Iran and Israel, the dominant narrative of the media was from above and from the perspective of the aggressor, but female journalists, despite the danger of bombing, censorship, and threats, decided to tell the story from the heart of life and write the truth. War is gendered and the experience of war is not the same for men and women (9), as was the case in the 12-day war between Iran and Israel.

During war, a pregnant woman’s body becomes both a host for life and violence. The pregnant woman, who tries to maintain inner peace amidst the sound of sirens and trembling walls, embodies the concept of “silent resistance”. This moment shows how women’s daily decisions take on a political color, as preserving life against the logic of death is a political act. (10) Furthermore, a woman’s body is not only a site of experience, but also a carrier of the memory of war. In Niloufar Hamedi’s narratives of the 12-day war (11), women are depicted at the borders of the country, in a state of suspension and homelessness, redefining crying as a liberating act. Contrary to clichés that equate resistance with silence, these women show that expressing emotions is a form of resistance. War wounds the collective memory, but women’s narratives, through reconstructing memories and mourning, keep this memory alive. Women journalists are not only recorders of

Journalism as a form of resistance, feminine action in the midst of crisis.

For women journalists working in Iran, staying in a bombarded city is not a simple choice, but a costly decision that oscillates between survival, responsibility, and commitment. Dedicated female reporters, even in the face of censorship and threats, wrote with intelligence, removing precise locations, but teaching people how to protect their children. This form of writing is a form of “ethics of care” in the midst of violence. (14) But the costs were heavy: threatening calls, the danger of arrest, and in some cases, death under aerial attacks. The attack on Evin Prison, this blatant war crime, showed that writing the truth about prisoners who are caught in the double oppression of domestic and foreign attacks, many of whom are opposition activists unjustly detained, is always accompanied by danger in Iran. Another important aspect is that in the narratives of female journalists, children have a prominent presence. Children who interpret the sound of sirens as gunfire or are silenced by the first smile with the sound

The narrative of women about war is not just a footnote, but the heart of truth. These narratives show that war is not just a conflict between governments, but a human experience that involves the body, emotions, and memory. Without hearing the voices of women, a complete picture of war cannot be formed. The female journalists who wrote about this war are the keepers of collective memory; women who, with their pen, save the body of the city and the female body from becoming mere statistics and headlines. In a world where major media outlets focus more on power games, the narratives of these women serve as a reminder that the heavy burden of war on women, often hidden in the margins, is where women bravely and consciously turn their narratives into resistance.

Notes:

1- The war has affected more than 600 million women and girls, according to the United Nations report, Associated Press, 2023.

2- War Against Women: The killing of women in armed conflicts doubled in 2023, according to the United Nations Women’s Organization (UN Women), 2024.

3- Women and War. IPAS News Agency, 2023.

4- The health of women and girls in conflict-affected areas. Global Citizen, 2023.

5- Examination of militarism and violence against women. PeaceWomen.org.

6- Twelve Days Under Fire: Comprehensive Report of the War between Iran and Israel.

Hirana News Agency.

June 27th, 2025

7- Kakberen, C. Anti-Militarism: Political and Gender Dynamics of Peace Movements. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

8- Inlow, C. Museums, Beaches, and Bases: A Feminist Understanding of International Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

9- Tickner, J. A. Gender in International Relations: Feminist Perspectives on Achieving Global Security. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

10. Butler, J. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso, 2004.

11- Giving birth under bombardment.

“Shargh Newspaper.”

July 2nd, 2025

12- Mohanty, C. T. Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

13- Hirsh, M., & Smith, W. Feminism and Cultural Memory: An Introduction. Signs Journal, 2002.

14- Toronto, J.S. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for Care Ethics. London: Routledge, 1993.

Leymah Gbowee, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Tags

Elahe Amani Fire extinguisher Goddess Amani Peace peace line Peace Line 172 The war between Iran and Israel. Twelve-day war War War victims Women and War ماهنامه خط صلح