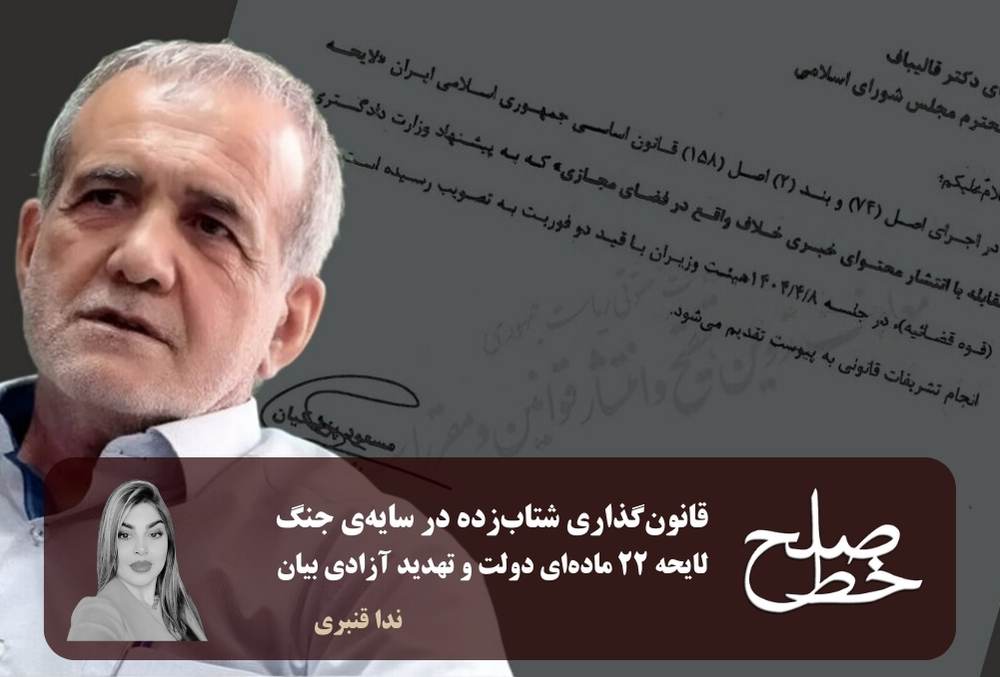

Legislating in the Shadow of War / Neda Qanbari

When asked about the 12-day war and its consequences, my mind doesn’t go to anything but images of destruction and the sound of bomb explosions. I think more about the days when “silence” after the war was heavier than any explosion, engulfing the entire country. In those moments, just when we expected peace after the crisis, an important event occurred in the legal and social realm: “The bill to combat the spread of false news content in the virtual space”, with a seemingly peaceful title, was quickly presented and approved, under the pretext of preserving the mental peace of citizens, and put a part of the public’s hope at risk.

A knowledgeable lawyer definitely knows that the post-war era is one of the most sensitive periods for freedoms and civil rights. Historical experiences also show that governments, in such situations, pass restrictive laws under the pretext of security. This was the same process that occurred in Iran after the twelve-day war.

Twelve days after the first explosions, a state of emergency was declared. On the surface, the military crisis had ended, but in reality, a process had begun that could intensify restrictions on freedoms. After the end of the war on June 12, the country was in a state of turmoil but hopeful. In this situation, the government sent a 22-article bill to parliament to control the spread of false news. (1) Many saw this as a necessary step to reduce distrust and prevent dangerous rumors, but it also raised the question: Is this bill choosing to protect the truth or beginning to restrict freedoms? The content of the news, whether it was false rumors or critical and documented reports, all depended on the judgment of the implementing authority. The urgency and speed of the bill’s progress only increased concerns. The bill was sent to parliament on July 21, 1985 and was passed with 205 in favor, 49 against, and 3 abstentions on August

The Center for Parliamentary Research announced: The first part of the bill (articles 1-11) is acceptable with some amendments, but the second part (articles 12-22) suffers from inflation of criminal laws and conflicts with general legislative policies. (2) The two-week deadline practically eliminated the opportunity for thorough examination and public discourse. In the post-war conditions, this action could have used superficial public support to pass severe restrictions, restrictions that would have faced public resistance in normal circumstances. The broad definitions in the bill provided the possibility of prosecuting any type of media activity or online expression. Articles 12 to 22, with heavy enforcement guarantees, had a more punitive and suppressive approach rather than a regulatory one. The Center for Parliamentary Research also warned that such criminalization does not align with the principles of criminal law and the country’s criminal policy.

If we examine this issue from an international perspective, Iran is committed to important documents in the field of freedom of expression and access to information. This includes the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which states that any restriction on freedom of expression must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate. In practice, this means that restrictions must be clearly defined, have a legitimate purpose, and impose the least amount of pressure on individual freedoms. The 22-article bill, with its vague definitions and heavy enforcement guarantees, does not comply with these standards and its approval would effectively violate Iran’s domestic laws and international commitments.

From a historical perspective, post-war limitations, under the pretext of maintaining security, often remain for years. Examples such as the Patriot Act in the United States after 9/11, or cyber security laws in some Asian countries, show that emergency situations – even after the initial threat has been eliminated – often turn into a new normal. These experiences warn that the hasty adoption of laws can have long-term and lasting effects on civil liberties.

The social and psychological consequences of passing this bill are also noteworthy. The first impact is a decrease in public trust in the media and officials. When citizens see that any expression of opinion or news can be perceived as a crime, the tendency towards self-censorship increases. This phenomenon not only limits the space for criticism and dialogue, but also poses a threat to transparency and accountability of the government. As a result, civil society is harmed and public participation in political and social decision-making decreases. Along with these issues, the psychological effects on citizens are also important. The constant pressure to comply with legal restrictions leads to increased anxiety and fear, and can reinforce feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness. Post-war experiences have shown that these pressures can lead to the formation of an internal censorship culture in society, which makes restoring freedoms even more difficult after amending laws.

Another point is that the precise legal analysis of each article is important. The first part of this bill (articles 1-11) was designed to combat completely false news or destructive rumors and could have been defensible within the framework of conventional legal principles. However, the second part (articles 12-22) included heavy criminal sanctions and vague definitions that effectively covered any media activity and even personal online expression. Such a combination of vague definitions and heavy punishments is unacceptable from a criminal law and freedom of expression perspective.

The reaction of the legal community and media was immediate. The wave of criticism from lawyers, journalists, and civil activists prompted the government to send letters on 12 August to return the bill to the parliament. Experience has shown that this temporary retreat does not necessarily mean abandoning the idea completely, as similar bills can return under a new name and packaging, especially if post-war conditions and public pressure continue to exist. In this regard, a comparison with international laws is instructive. The European Convention on Human Rights and the procedures of the European Court of Human Rights emphasize that restrictions on freedom of expression must be transparent, necessary, and proportionate, and any criminal penalties for disseminating information must be severely limited and clearly defined. The experience of different countries has shown that vague and severe laws, instead of reducing crises, lead to increased distrust and the creation of new social crises.

From a psychological perspective, the post-war period is the most sensitive time for society. People in this period need peace, hope, and opportunities for reconstruction. The hasty approval of restrictive laws, as seen in the draft, can limit this opportunity and lead society towards social contraction and reduced civic participation.

As an international lawyer, I believe that the duty of the legal community is not only to critique laws, but also to promote public legal awareness. People should know the impact of each article and clause on their daily lives. Public awareness is the only true shield against the adoption of restrictive laws. The 12-day war was not just a military crisis, but a test for democracy and the rule of law. The hasty adoption of this bill is an example of using emergency situations to change the rules of the game. Even with the temporary withdrawal of the bill, there is still a risk of its return under a different name. If civil society, media, and legal institutions are not vigilant, the threat of limiting freedoms will remain.

Notes:

1- A bill for combating rumors and fake news was submitted to the parliament, according to the news agency.

Tasnim.

“31st of Tir month, 1404.”

2- Expert opinion on: “General provisions of the draft law on combating the dissemination of false news content in cyberspace”.

Center for Research of the Islamic Consultative Assembly.

August 27th, 2025

Persian Wikipedia..

Tags

Draft of 22 articles Espionage Espionage for Israel Fire extinguisher Masoud Pazhakian Neda Ghanbari Peace peace line Peace Line 172 The war between Iran and Israel. War ماهنامه خط صلح