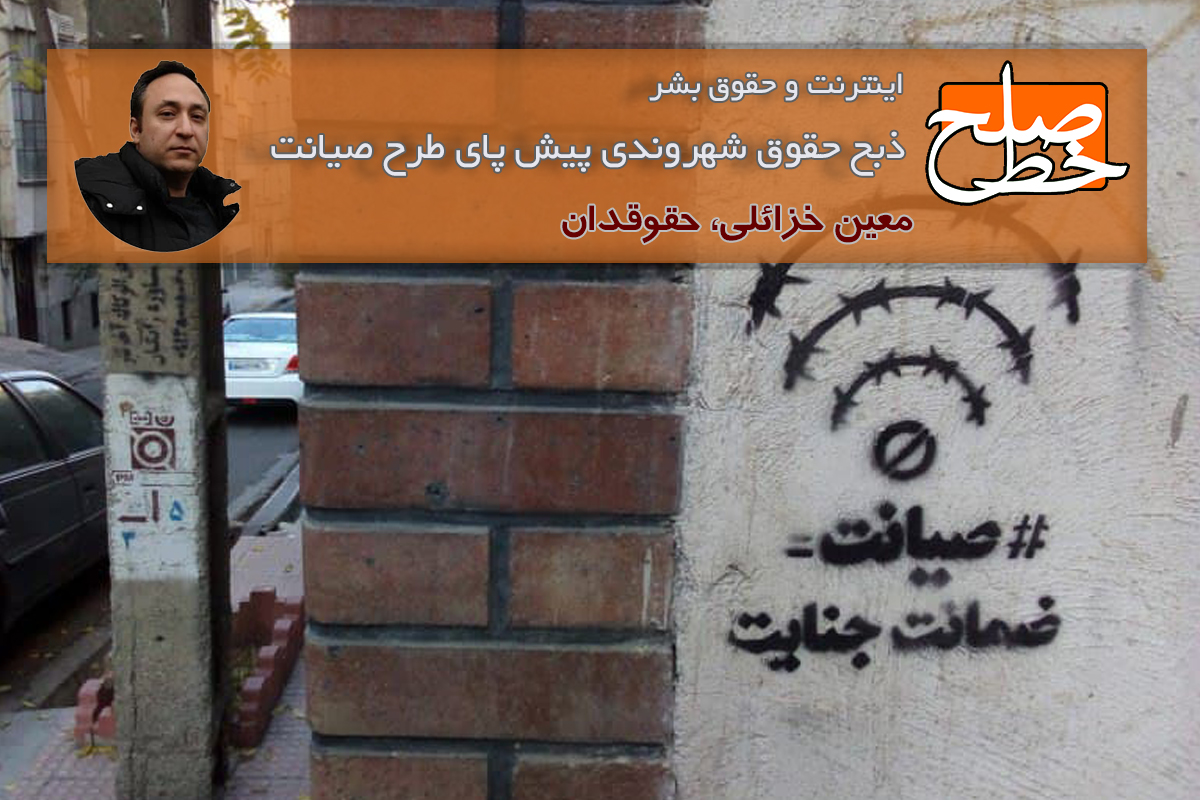

Violating citizens’ rights in front of the conservation plan/ Moein Khazaeli.

Overview of the plan for protecting the rights of users in the virtual space, which was presented under the new name “Virtual Space Services Regulations Plan”, was approved in the special commission of twenty members of the parliament in February 2022. According to legal experts, this plan is not capable of becoming a law and is in violation of both domestic and international laws.

Although the general approvals were canceled shortly by the Presiding Board of the Islamic Consultative Assembly due to what was called “formal objections”, according to Mehrdad Vais Karami, the Secretary of the Joint Special Commission for Reviewing the Protection of Virtual Space Plan, this plan is a “governmental plan” and will undoubtedly be implemented for a trial period in Iran.

The explicit confession of the secretary of the special commission for reviewing the protection plan regarding the position of sovereignty in Iran shows that the formal annulment of the plan by the presiding board of the parliament, as announced, is only “formal” and after addressing this issue, the plan will ultimately be approved and implemented. This firmness of sovereignty in Iran for the implementation of the protection plan is at a time when the result of implementing this plan not only violates the fundamental human rights of citizens, but also contradicts the relevant domestic laws.

The right to access the internet is included in human rights laws.

Although the right to free access to the internet is not directly mentioned in classic international human rights documents, modern interpretations of this right include the freedom of expression and, in particular, the right to free access to the flow of news and information. Therefore, it can be considered a fundamental human right. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights explicitly recognizes the right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to express opinions and thoughts in any form, as well as the right to free access to thoughts and opinions.

In this regard, the European Court of Human Rights, in a case opened against the government of Turkey in 2012 by a Turkish citizen, explicitly recognized the right to access the internet as an “indivisible” right, in contrast to the right to freedom of expression. According to the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights, “the right to access the internet is inseparable from the right to access information and communication, which is protected by many constitutional laws, and it includes the right of every individual to participate in the information society and the obligation of governments to ensure access to the internet for their citizens.”

Access to free and appropriate internet, in addition to being a means of ensuring the right to freedom of expression and access to free flow of news and information, has become a tool for securing other fundamental human rights in today’s world, especially the right to education, economic rights, and individual and social rights. Any disruption to this access will ultimately lead to a violation of these fundamental human rights.

Nowadays, the dependence on the right to education and economic rights on the internet is to such an extent that not having access to it practically results in citizens’ inability to benefit from their right to education and economic rights. Since from a legal perspective, commitment to upholding human rights is also considered a commitment to providing and ensuring the necessary tools, governments are obligated to provide their citizens with access to these rights, especially the right to education and economic rights, in order to meet their basic needs. This includes providing access to the internet.

The tool for guaranteeing internet access is not just a theoretical claim and has been referenced in international legal proceedings, especially in human rights issues. For example, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2016 that a prisoner in Estonia must be provided with internet access as a means of guaranteeing their other rights. In this case, the prisoner claimed that they needed access to three legal websites in order to defend themselves in court, but the Estonian government had blocked their access. In addition to guaranteeing internet access as a human right, the European Court of Human Rights recognized it as a tool for ensuring the right to education and access to justice, and ruled in favor of the prisoner.

Furthermore, access to free internet plays a crucial role in the development of democracy and human rights. It is an undeniable fact that in today’s world, without access to the internet, access to news and information, especially news production tools such as the media, is practically impossible. Therefore, the role that the media used to play as the fourth pillar of democracy is now being played by free internet. The role of social networks in holding governments accountable, particularly in exposing their hidden faces in violating human rights, is of the same nature and its function has also been observed, albeit to a limited extent, in recent years in Iran.

In addition to being completely contrary to the provisions of the Safeguarding Plan with international human rights laws, the provisions of this plan are fundamentally in conflict with the principles and requirements of legal science, especially legislation. In the process of drafting and approving a law, what is as important as the text of the law is the possibility of implementing the intended law, both sociologically, legally, and technically. This means that, for example, passing a law that is practically impossible to implement is not only a futile and meaningless effort, but also undermines the position of the law and the legislator in society and turns laws into worthless and insignificant texts in practice.

The examination of the contents of the conservation plan, however, indicates the high potential of this law in its implementation. The obligation of internet service companies, social networks, and messaging apps such as Google, Instagram, and WhatsApp to establish offices in Iran despite heavy international sanctions, the requirement for all internet users to identify their identities, the obligation of major mobile phone manufacturers to install Iranian applications on their phones, and especially the obligation of citizens to use Iranian apps instead of foreign ones, are among the issues that their implementation is highly doubtful and uncertain. Therefore, it is not clear why a plan that is still far from being implemented should be turned into a law.

Nowadays, many countries also recognize the right to free access to the internet as one of the fundamental rights of citizenship in their domestic laws and consider it the duty of the government to provide and guarantee it for citizens. For example, in France, the use of free internet is one of the fundamental rights of citizens and this was emphasized in a ruling issued by the Constitutional Council of this country in 2009. According to this ruling, since access to communication services (including the internet) is a fundamental right, creating any obstacles or blocking it will only be possible with a court order and after a fair and balanced legal process that takes into account the precise interests of both parties.

According to the Constitutional Court of Costa Rica, access to the internet is considered a fundamental right of citizens and ensuring this right is one of the duties of the government.

In some countries, including Spain, Finland, Estonia, and South Africa, although the right to access the internet is not officially recognized as a fundamental right, lawmakers in these countries have guaranteed the right to access the internet for all citizens by passing specific laws. For example, in Finland, the “Communications Market Act” emphasizes the responsibilities of the government and private sector in providing internet access to citizens and even sets the available internet speed.

The right to access the internet is included in domestic laws in Iran.

Despite the explicit recognition of the internet as a fundamental right of citizens or a necessary right for ensuring in the domestic laws of many countries and the implicit emphasis of international human rights laws on the internet as a tool for securing and guaranteeing human rights, this right is faced with a strange void in the domestic laws of Iran and no law explicitly highlights citizens’ access to the internet.

The fact that this is not explicitly recognized does not mean that systematic and organized disruption of citizens’ access to the free internet is even legally permissible through the adoption of authorized and legitimate laws. This is because preventing access to the free internet is not guaranteed in the relevant laws, but the rights that are violated by doing so, including those that are prohibited by law in Iran, are among the rights that can only be violated on a case-by-case basis and with a direct judicial order.

As an example, since the implementation of the plan to protect the virtual space means systematic censorship and especially invasion of citizens’ privacy through surveillance and eavesdropping, it is contrary to the explicit provision of Article 25 of the Constitution; therefore, according to this principle, any recording and disclosure of telephone, telegraph, and telex conversations (and their modern equivalents such as internet messaging chats) as well as censorship, eavesdropping, and surveillance of citizens’ privacy is prohibited; while the purpose of the plan to protect the virtual space explicitly obligates internet service providers to record and provide access to information in the virtual space, especially user information, in an unspecified and unlimited manner upon request of “competent authorities”.

In legal terms, this means that, for example, a law is passed that requires telecommunications companies to record all phone conversations of citizens and only provide them to unidentified “authorized” institutions upon a simple request.

On the other hand, since the effort to pass a bill for protecting the virtual space would practically mean disrupting the legitimate freedoms of citizens, therefore, limiting and imposing restrictions on it, even with the establishment of laws and regulations based on Article 9 of the Constitution, is prohibited in Iran.

In the law of “Regulations and Rules of Computer Information Networks”, “Regulations for Organizing Internet Information Bases” and also regulations related to e-government, the right of citizens to access the internet is considered as a means of ensuring free access to knowledge and information.

At the same time, the only document that explicitly and directly identifies the right to access the internet in Iran is the Charter of Citizens’ Rights, enacted in 2016 during the administration of Hassan Rouhani. According to section H of this charter (articles 33, 34, and 35), free and non-discriminatory access to the virtual space and the internet is the right of all citizens, and creating restrictions and filtering is prohibited. Additionally, based on the emphasis of this charter, citizens in the virtual space must have privacy and cyber security. Although this charter does not have enforceable guarantees and is not considered a law in this regard, as copying is a conceptual understanding of existing laws in Iran, the realization of its provisions has been guaranteed by relevant laws.

However, the plan for protection, despite its structural flaws, for the assistance of laws and the presiding board of the Islamic Consultative Assembly in Iran is merely a formal violation that has been prioritized and has been able to temporarily cancel the approval of the special commission in February; while the content of this plan is fundamentally and inherently contradictory to human rights and citizenship rights of citizens in Iran and if implemented, will lead to a human rights disaster in Iran.

Tags

Censorship Citizenship rights Filtering Human rights Internet Islamic Consultative Assembly Maintenance plan Monthly Peace Line Magazine peace line Peace Line 131 The Commission for the Protection of the Parliament ماهنامه خط صلح