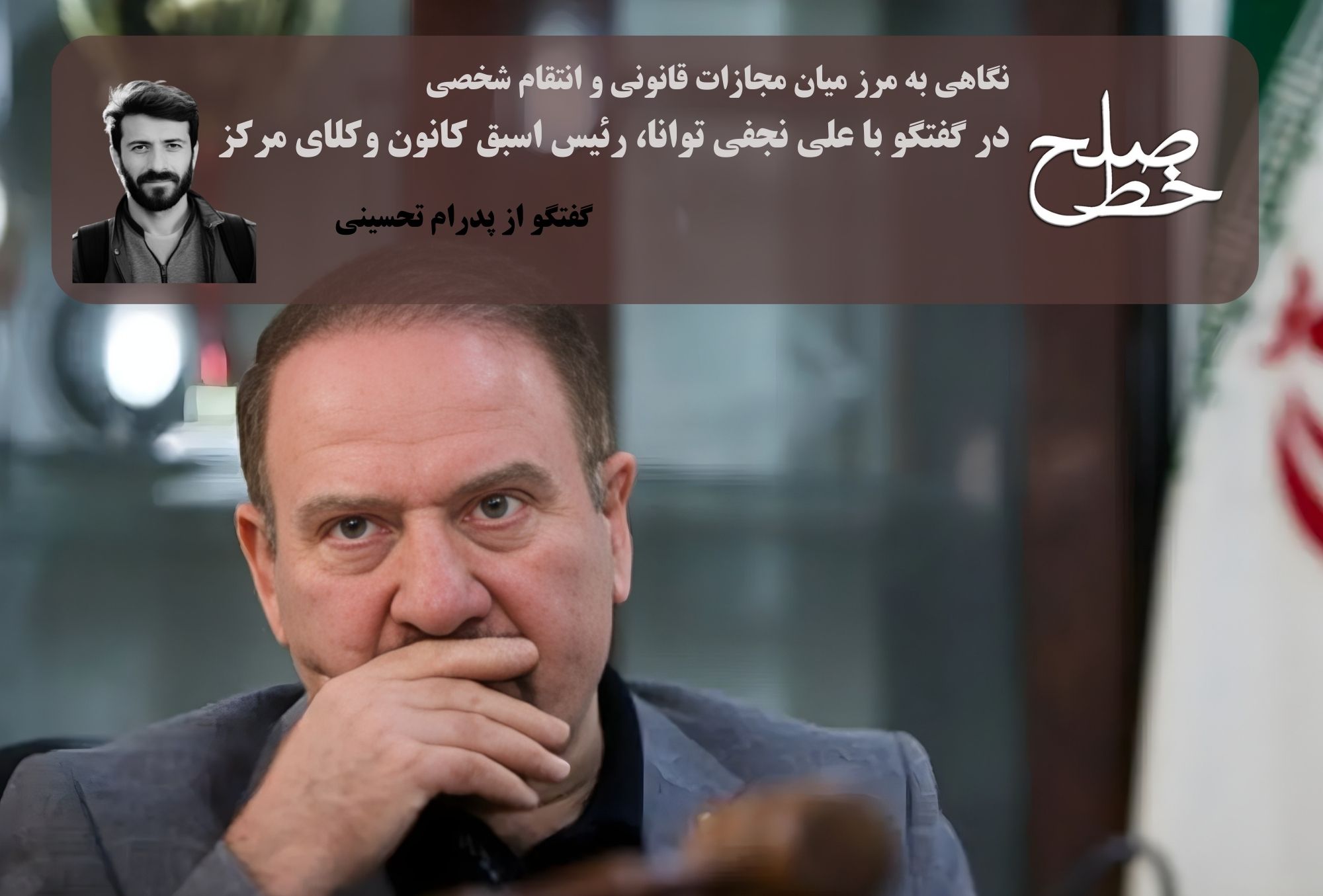

A Look at the Line Between Legal Punishment and Personal Revenge; A Conversation with Ali Najafi Tavana/ Pedram Tahsini

Ali Najafi Tavana was born in 1953 (1332) in the Alamut region of Qazvin. He completed his primary education in Tonekabon and graduated from Hafeziyeh High School in the same city. In 1972 (1351), he was admitted to the Faculty of Law at the University of Tehran, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in judicial law in 1975 (1354). In 1979 (1358), Najafi Tavana traveled to France and pursued advanced studies in criminology and criminal sciences at the Faculty of Law and Humanities at the University of Toulouse. He eventually earned his doctorate in law after defending a dissertation titled Juvenile and Youth Offenses.

In this issue of Peace Mark Monthly Magazine, we sat down with this university professor and former head of the Central Bar Association to discuss the causes of the rise in personal acts of revenge amid a lack of trust in the judiciary. According to this legal scholar, revenge-driven actions cannot be directly and simply reduced to the inefficiency of the law or the collapse of the rule of law; rather, the roots of this phenomenon are better sought in cultural, psychological, and social traditions.

The full Peace Mark Monthly Magazine interview with Dr. Najafi Tavana is as follows:

From a public law perspective, when a citizen concludes that the judiciary is neither impartial nor effective, can we say that the “right to effective access to justice” has essentially been violated in Iran? In your view, where and how exactly does this violation occur?

To judge whether a country’s justice system is efficient requires thorough analysis and statistical data. However, the fact that some individuals resort to retaliation, qisas, or personal revenge is not fundamentally linked to the effectiveness of a country’s disciplinary, judicial, or oversight system—or if it is, the connection is not very significant. As you know, in most countries, when personal revenge comes into play, many victims themselves seek retribution and take justice into their own hands. This phenomenon is seen not only among gangsters and rival groups but also in conflicts involving sports groups. For example, in clashes between Liverpool and Manchester fans, or in the United States between fans of various sports teams like basketball. Therefore, this phenomenon is not unique to any one country.

Moreover, in traditional societies, qisas was prevalent in a way that, if a family member was killed, the entire opposing family would be drawn into a feud as part of a revenge process. In our country as well—one transitioning from agricultural industries to other advanced sectors and entering into modern and postmodern discussions in the field of small industries—this perspective of personal revenge still persists. In other words, this view is so deeply embedded in our culture that in the western and eastern regions of the country—or even in the south—if a girl from a family seeks refuge with a stranger—or even, in cases I am personally aware of, merely chats with someone—the girl’s family, to preserve their honor, may attack and kill her.

Another point is that we know in some regions of the country—from east to west—when a girl or boy is raped or killed, if a complaint is filed and proper evidence is provided, we’ve seen cases where the perpetrators of such atrocities have been sentenced to death. Nevertheless, in some instances, no one waits for legal action; instead, the situation is treated as a familial duty and tradition. Such an act is considered a form of honor and traditional solidarity, whereby family members, bound by blood ties, feel obligated to personally retaliate against the murderer or assailant.

Unfortunately, we still witness this in many tribes and ethnic groups where such actions are recognized as customary practices. The primary reason may be the lengthy judicial processes and the slow, arduous legal path—even though they know that if a father kills his child’s murderer, he will certainly not face qisas. This is anticipated in the law: in such cases, the individual will be sentenced to imprisonment but not qisas. In contrast, in many other countries, a person committing such an act would face severe penalties.

However, let me also note: In the five decades of my professional legal work, especially in recent years, I have rarely encountered such revenge cases.

So, in your view, this is a recurring issue. But in criminal law, where exactly is the clear line between “legal punishment” and “personal revenge”? And why does it seem that this line has collapsed—or been deliberately blurred—in public opinion in Iran?

I’m not quite familiar with the language you’re using. The idea of a collapse or disappearance of this line, in my opinion, is more a judgment based on certain specific examples. In practice, in many cases, when a crime occurs, the victim’s family turns to the judiciary. And as I mentioned—given certain traditions, especially in small towns—we do not see the majority you are referring to. People do report crimes, but the legal process is lengthy, there are no witnesses, and the individual, believing that the perpetrator had prior threats or a criminal background and has now committed murder, concludes that they must take matters into their own hands.

Thus, they find and kill the person they believe to be the murderer. Or, in cases where they realize their daughter or son has been raped, they suspect—or even are certain—that a specific person is the rapist. In such circumstances, the desire for revenge and justice becomes so intense that psychologically, the individual loses the ability to manage and control the situation. Instead of waiting for justice to be served through legal channels, they directly attempt to carry it out themselves.

When someone resorts to violence instead of turning to the courts, is that merely an individual crime? Or does it reflect the state’s structural failure in monopolizing justice? From a legal standpoint, what is the state’s role in this cycle?

I have always been a critic of many social and administrative issues, and I have written about them for decades—and paid the price—but I must say that this is not the true reality. In fact, if a complaint is filed, our judiciary is one of the strictest systems in this regard. In France, if you commit murder, the maximum sentence is life imprisonment. In the U.S., the death penalty is only carried out in certain states; in others, it’s life or long-term imprisonment.

But our country has the harshest judicial system in this regard. In Iran, the punishment for murder and rape is qisas and execution. The problem, perhaps, lies in presenting evidence. However, when I compare our legal system, with the knowledge I have of global laws, I can say Iran has one of the strictest criminal justice systems. As such, the severity of punishments here is much higher than in many other parts of the world.

In cases like the killing of the Yasouj doctor, can it be said that the inefficiency in addressing medical malpractice and the lack of a transparent complaint process acted as a “facilitating cause” in the murder? Is this issue legally traceable in Iran, or is it deliberately overlooked?

No law anywhere in the world is perfect. I have studied most of the world’s laws since I am both a teacher and researcher. All laws are always undergoing revisions. Until 1966, England relied on precedent and had no codified law. From that year on, they passed laws. In our country, too, laws are certainly not flawless or finalized—they are in a process of transformation.

As for medical malpractice, we actually have a law that states if a doctor fails to follow medical regulations during treatment—whether due to carelessness, negligence, or incompetence—and a crime occurs, they are punishable.

So in your view, the law itself is not the problem here.

Laws are the product of human minds. And perhaps we don’t think perfectly. I, too, have criticisms of this law—you can find them in my books. But this doesn’t make the law ineffective. The issue is more in the implementation. Still, don’t forget that Iran has one of the highest rates of criminal prosecution. This shows that, regardless, the judiciary and law enforcement are actively pursuing crime.

There are many cases in London where people are stabbed, and murders and looting happen in group conflicts. These issues are tied to individuals’ personal, public, and group cultures.

In modern legal literature, there’s a term called “restorative justice” that replaces violence and revenge. Do you think, within Iran’s current legal framework, restorative justice is achievable? Or is the judicial structure inherently incompatible with it?

This concept, in practice—though not systematized—has long existed in our system, in families, and in tribal mediation groups. We’ve had concepts like blood-money negotiations and giving a daughter in marriage as reparation. If a crime occurred, families would offer a daughter in marriage. We’ve had legal provisions for pardon, the House of Kindness before the revolution, the Arbitration Council after the revolution, mediation, and many other similar structures. Restorative justice exists in practice, and it’s even anticipated in the new law.

So you believe that this concept of restorative justice appears in Iranian law, albeit in a different form.

Yes, it has been anticipated. But restorative justice requires mechanisms. It needs cultural groundwork to be accepted. And in that, we haven’t been very successful.

In some cases, like the murder of the Yasouj doctor, we see media narratives turning the avenger into a hero. From a media law and criminal liability standpoint, can this kind of narrative be considered indirect encouragement of crime or weakening of public order? Why is it not confronted?

In the laws of our country, like in all Islamic countries, if someone commits murder, they are mahdoor al-dam (deserving of death). But still, as humans, we seek revenge. A patient is treated by a doctor and then dies. The patient’s family attacks the unfortunate doctor. Or a lawyer defends a defendant and is attacked and killed. Or a judge issues a ruling of qisas or execution, and the victim’s family attacks and kills the judge.

These things relate to the history and culture of countries. They exist in most parts of the world. Even in American films, you see that victims’ families don’t wait for the judiciary to act. Surely, you’ve seen a film by Charles Bronson, where, after a group of thugs kills his wife, he takes revenge using a sock filled with coins as a weapon.

There are many such examples. Our country is no exception. Look, I myself criticize the judicial system’s performance, but when I’m asked a question, I must speak with academic integrity. I’m not here to condemn one side or another for any reason.

A while ago, some British parliamentarians visited Tehran and came to the Bar Association. They said, “In Iran, children are executed.” I said, yes, children who have reached puberty can be executed for the crimes they commit—and I personally criticize that as well (see my book on juvenile delinquency). Criticism exists worldwide. Laws are reflections of society’s needs.

In tribal regions, we see social legitimacy granted to revenge. In your view, has the law in Iran succeeded in asserting itself above custom, tribal codes, and local notions of honor? If not, is this a legal failure or a political one?

With all due respect, don’t expect a political perspective from someone with fifty years of legal experience.

We don’t expect that at all. I didn’t mean political analysis.

I understand. Still, as someone deeply familiar with these issues, I’m here to help inform your readers. So, when someone seeks revenge, it doesn’t necessarily mean the judiciary is ineffective. In England, Europe, India, China—everywhere—revenge exists. The point is, the individual, under intense emotions, fails to manage or control themselves. Their emotional resistance breaks down, and instead of going to the judiciary, they act in haste and deliver punishment themselves.

This is a bitter reality that exists all over the world. The thirst for revenge is only quenched by striking back. Let me remind you: one must be fair in judgment. I’ve been disqualified from legal candidacy in Iran several times, even when I ranked first. But when asked to judge, I don’t act out of personal revenge—I act based on justice, because I must. As Dr. Ali Najafi Tavana and a well-known professor, certain expectations come with the role.

Our country has extremely strict laws for dealing with criminals. But if someone, say, attacks my father and I act without waiting and follow traditional behaviors, that stems from historical, ethical, cultural, and traditional views. While we imitate industrial countries, our culture is still traditional. Even though, after COVID-19, emotional and moral connections have diminished and families interact less, the spirit of revenge still prevails in some small towns, tribes, and clans.

As a final question: If the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence—which is the foundation of the modern state, as you also stated—has essentially collapsed, can we still speak of the “rule of law” in Iran? Or have we entered a stage where the law is only enforced against the weak?

Remember that laws are the process and outcome of governance and a necessity. In the U.S., someone like Trump—a real estate broker—became president. As a legal expert, I find his behavior inappropriate. Or take former French President Sarkozy. Laws are shaped by the views of representatives elected through money and power. Nowhere in the world are representatives truly representative of the people. In the U.S., Trump’s supporters stormed Congress after the last election—what happened to them? Basically, capitalists and cartels run the world.

Let me be blunt: those who claim to be spending money for developing nations are not after the interests of the Global South, my friend. Our government is not ideal—we criticize it, we pay the price, and we all suffer for it. We are all burdened by inflation and structural imbalances. But look around the world—they kill with silk gloves. Who started the Russia–Ukraine war? Rusty weapons from Europe and the U.S. have been dumped into this battlefield under the name of democracy while their resources are plundered.

Iran has problems—we know it and we criticize it—but the truth is that the world is governed by rulers chosen by the powerful. Therefore, expecting the rule of law in practice is essentially expecting a rule of law imposed by the wealthy. In criminology, we have a theory called Conservative Criminology, which began with Thatcher and Reagan, was strengthened by Bush, and is nearing its end with Trump.

Thank you for your time with Peace Mark Monthly Magazine.

Footnotes

Death Wish (1974) starring Charles Bronson as Paul Kersey. In the film, the main character becomes a vigilante after his wife is murdered. One famous early scene shows him using a coin-filled sock as a makeshift weapon for self-defense and revenge.

Conservative Criminology is a political-ideological approach in the field of criminology that aligns with right-wing (conservative) perspectives. It contrasts with dominant liberal or leftist theories and emphasizes:

Individual Responsibility: Viewing crime as a result of personal, rational choices rather than solely structural factors like poverty or social inequality.

Strict Control and Punishment: Advocating for policies like zero-tolerance policing, harsher penalties, and a deterrence focus to reduce crime.

Critique of Liberal Ideology: Asserting that academic criminology often suppresses conservative viewpoints due to left-leaning biases.

Tags

Bar Association Doctor Yasouj Execution Judiciary Justice in humanity Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province Mahmoud Ansari Masoud Davoudi Medical malpractice Murder peace line Peace Line 176 Pedram Tahsini Personal revenge Revenge Rule of law Yasuj ماهنامه خط صلح