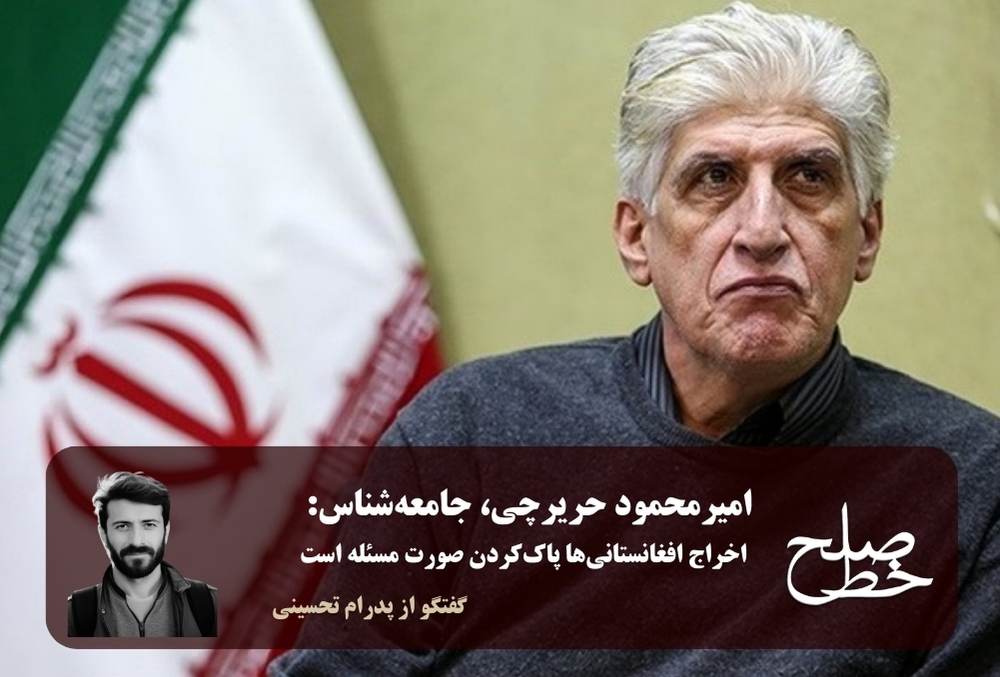

Amir Mahmoud Harirchi: Deporting Afghans is just sweeping the problem under the rug/ Pedram Tahsini

Migration is not a new story; it is an ancient narrative embedded in the annals of every nation’s history — filled with tales both great and small, of triumphs and defeats. But for the people of Afghanistan, this narrative is steeped in sorrow. It is a historical pain for our eastern neighbor, who also happens to be our cultural kin — a people who, not long ago, during the last century, saw Iran’s land and culture as intertwined with their own destiny. The joyful days of the oppressed people of Afghanistan are so rare and fleeting that they hardly register in the course of history.

Since gaining independence, the people of Afghanistan have been perpetually in search of refuge, and their first and most important destination has always been Iran. This trend accelerated, especially with the rise of the Taliban — who, for the second time, seized control of the country and continue to rule. In recent years, particularly since 2021 (1400), the wave of migration from Afghanistan has surged to unprecedented levels. As their presence and impact in Iranian society have grown over these years, internal opposition has intensified — to the point where, over the past year, official campaigns have formed to deport them.

In the past year, with the start of Iran’s fourteenth government, the plan to deport “illegal foreign nationals” was placed on the agenda. After a twelve-day war and under the pretext of security concerns, this effort intensified. According to official figures from the Ministry of Interior, thus far, 1.2 million people have left Iran “voluntarily” or “forcibly.” However, several domestic social activists have voiced their opposition to the essence or implementation of this plan — especially the manner of these deportations — and have raised serious questions for policymakers.

In this context, Peace Mark Monthly Magazine conducted an interview with Dr. Amir Mahmoud Harirchi, sociologist and university professor. He considers Afghan migrants to be asylum seekers who were compelled by necessity to come to Iran. He believes that if a decision has been made for them to leave Iran, instead of labeling them with stigma, their rights must be respected. In part of his comments, this sociologist raises questions that are highly thought-provoking: Will subsidies be fixed if Afghans are deported? Will employment opportunities suddenly increase?

Here is the full interview with this university professor, conducted by Peace Mark Monthly Magazine:

As a sociologist, what factors do you consider important when it comes to decisions about deporting Afghan migrants from Iran? And how do you assess their arrival in Iran overall?

First and foremost, I must say that I deeply regret the current situation. These were people who sought refuge in our country. But throughout their time in Iran, many of them were severely exploited and abused by employers. Naturally, such experiences have led to reactions among some of them — reactions that may not be pleasant for some Iranians. But if we look at the root of the issue, the core question is this: how can we so easily deport individuals who sought refuge in our country — many of whom were even born here?

So you don’t believe this policy is right?

No, I do not. Look, they are being stigmatized, but what percentage of them actually fit that image? Many of them worked in construction or as street cleaners — just consider their jobs. Now we are facing labor shortages in these sectors. How do they plan to replace this workforce?

If there was uncontrolled entry, then that’s a problem related to our own governance. Why did previous governments allow this? They sought refuge during the Taliban era. It was estimated that five million Afghans entered Iran — and now they’re being deported like this. It is said that even individuals with Iranian residency cards and identification documents, including women and children, were among them. What was the reason for admitting them back then? The Taliban came, and they entered our country. If they entered illegally, then the authorities should have acted at that time. But they sought refuge.

One reason cited by those opposing the presence of Afghan migrants in Iran is the strain on national resources — for example, the Minister of Interior mentioned a six-percent decrease in bread transactions following the deportation of over one million Afghan migrants. What is your opinion on this?

What national resources? Shouldn’t someone be legally present in the country in order to receive subsidies? This six-percent decrease is just one of those claims. I’ve been saying this for ten years. Are we now counting bread transactions like it’s a math problem? What about the time when employers were exploiting them? Most of these migrants worked in construction, garbage collection, or street cleaning — with minimum or no wages and without insurance. These were jobs that Iranians were not doing. They should be considered part of the labor force — and only in certain cities, not the whole country. A workforce capable of working and supporting their families.

Why do you think anti-immigrant and anti-Afghan campaigns have increased in Iran over the past one or two years? Who do you think is behind them?

In my opinion, it’s an excuse — a way to say that the lack of jobs is because of the Afghans’ presence.

So you don’t believe there’s any systemic organization behind the part of Iranian society that supports the deportation of Afghan migrants? There was a campaign even before the fourteenth government took action, encouraging the government to act.

On what basis did they do that? What public survey was conducted to gauge the Iranian people’s opinions — to determine whether Afghans were causing problems in the country and therefore should be deported? Look, I agree that there should be an orderly and legal entry system. But these people sought refuge, and I’m emphasizing that word. Just as a number of Afghans sought refuge in Iran, just as many — and more — Iranians have gone abroad, both legally and illegally. Let’s examine why they sought refuge and why so many Iranians are eager to leave, even risking their lives to do so. We’ve had elites in our country who have left, and now we’re creating laws to prevent their punishment if they return. Punishment for what? Why should they be punished? Just as we’ve had waves from Afghanistan and previously from Iraq coming into Iran, we’ve also had outbound migration from Iran. Even now, there is a strong desire among Iranians to migrate.

Of course, comparing Iran to Europe may not be entirely appropriate. Europe has the capacity to absorb large numbers of migrants — especially elite ones. But Iran has not been a destination for elites from neighboring countries, particularly Afghanistan. Most migrants have been ordinary people…

Ordinary people from Afghanistan came because we couldn’t absorb their elites? Or do you believe Afghanistan has no elites? These are two separate issues. We can see Afghan doctors working in other countries — perhaps not in large numbers, but they do exist. We should investigate how our people view Afghans. I mean, will the subsidy system be fixed if they’re deported? Will employment opportunities increase if they’re expelled from Iran?

My question is: in places where Afghans were working, who is supposed to replace them now? I use the word “forced labor” for them — employed by various contractors who knew they were Afghan and, despite this, worked them hard and honestly.

The first issue is: why did they seek refuge in our country? Surely there were human rights reasons. But look how they are treated at the borders and consider what fate awaits them on the other side. With all our claims to being Muslim, how can we so willingly deport people like this, knowing what horrors await them on the other side? As fellow Muslims and people who share a language and culture, how can we behave this way? Does it really not matter to us what awaits them?

So you believe human rights should be the top priority here?

Yes, the main issue is their human and fundamental rights. How can you deport someone who was born in this country just because their father has legal issues? If the father committed a crime, arrest and punish him. But what about the contractor who employed him? In Hamedan, one such contractor pressured an Afghan worker so much that he went insane and committed a crime. These cases exist. We can’t bear to see the suffering of children in Gaza — it upsets us. So how can we send defenseless Afghan children across the border to face the Taliban? I’ve even heard that Afghans on the other side voluntarily came to welcome and assist them. Meanwhile, in Iran, landlords refuse to return deposits or tear up their identification cards. In my view, society has become swept up in hysteria.

What should be done?

What should be done!? In my opinion, there needs to be order and structure. If we emphasize “Islamic compassion,” then that compassion must be applied within a systematic and organized framework — meaning we should keep the migrants in the country and regulate their presence. If they are working, it must be within a defined legal framework. Have you ever seen an Afghan begging on the streets of Iran?

The government also says regulation is necessary, and part of this “regulation” is deporting “illegal foreign nationals.”

So are all those remaining in the country considered legal? Is there actually an assessment of the living conditions of those deemed legal? If we don’t care for the people who sought refuge and were officially recognized, is that humane? Is it compatible with human rights? Deportation merely wipes the issue off the surface — it doesn’t solve or regulate it.

Could you elaborate more on your proposed solution?

We need to identify where the rights of these individuals are being violated. For instance, if someone is working, receiving wages, and even legally recognized — are they being insured? If their employer fires them, where can they file a complaint? Even among Iranians, there are many whose rights are violated and who lack job security — they’re exploited as much as possible and then discarded. This situation must be corrected. The issue isn’t whether someone is Afghan or not — the core principle is that no human being should be subjected to forced labor. When a child is denied entry to school, what happens? They become child laborers. Official statistics show the number of child workers is increasing. Meanwhile, many Iranians with bachelor’s or master’s degrees are forced to drive for ride-hailing apps like Snapp. It’s only natural that such pressures and injustices ultimately lead to increased violence in society.

We are seeing how they’re being thrown out. A person rents a house, pays a deposit, and moves in — but now the landlord says they’re undocumented and refuses to return the deposit. Who is responsible for this? Where can they go to report that a landlord or employer mistreated them, withheld payments, or failed to pay wages for months?

Even undocumented migrants have rights. If other people’s rights are respected, then so should theirs. But when Iranians’ rights are not respected, it’s only natural that these people — especially because they are Afghan — suffer even more.

Very well, you say: “You are undocumented and for these reasons you cannot stay. We previously gave you refuge, but now the situation has changed, and we no longer want you here.” But what if this deportation leads to harm? Who are they supposed to turn to? Especially women and children, who are always more vulnerable. One person may have committed an offense — but what happens to his wife and children? That five- or six-year-old child, or the woman who came to Iran with hope while her husband was working endlessly — now, because they’re labeled “undocumented,” they want to expel them all.

When we speak of human rights, around the world — especially concerning migrants — the first concern is always women and children. Even if the decision is made to deport them, it must be done in a humane and just manner — not en masse and harshly, in a way that breaks countless hearts.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with Peace Mark Monthly Magazine.

Tags

Peace Line 172 The war between Iran and Israel. Twelve-day war