Generation of the 1980s: Hard Yesterdays, Harder Todays, Vanished Tomorrows/ Fereshteh Goli

In Iran, pension funds are financial-social institutions established to provide for individuals during old age and retirement. Their mechanisms rely on collecting insurance premiums from the workforce (employees and employers) and investing these funds, so that monthly pensions and other legal benefits can be paid to retirees. In essence, these institutions operate based on an “intergenerational solidarity” contract, meaning the premiums paid by today’s workers are used to fund the pensions of today’s retirees.

Pension funds in Iran are generally divided into three main categories:

Social Security Organization (SSO) Fund: This is the largest and most comprehensive insurance institution in the country, covering a large population of workers, private sector employees, and self-employed individuals either mandatorily or voluntarily.

Special Funds: This group includes the Civil Servants Pension Fund (for government employees in ministries and state institutions) and the Armed Forces Pension Fund (for personnel of the Army, IRGC, Basij, and Police). These funds typically operate under their own specific rules and regulations.

Exclusive Funds: These are created by large companies and organizations such as banks, the National Iranian Oil Company, and car manufacturers, exclusively for their employees, and often offer supplementary services in addition to basic benefits.

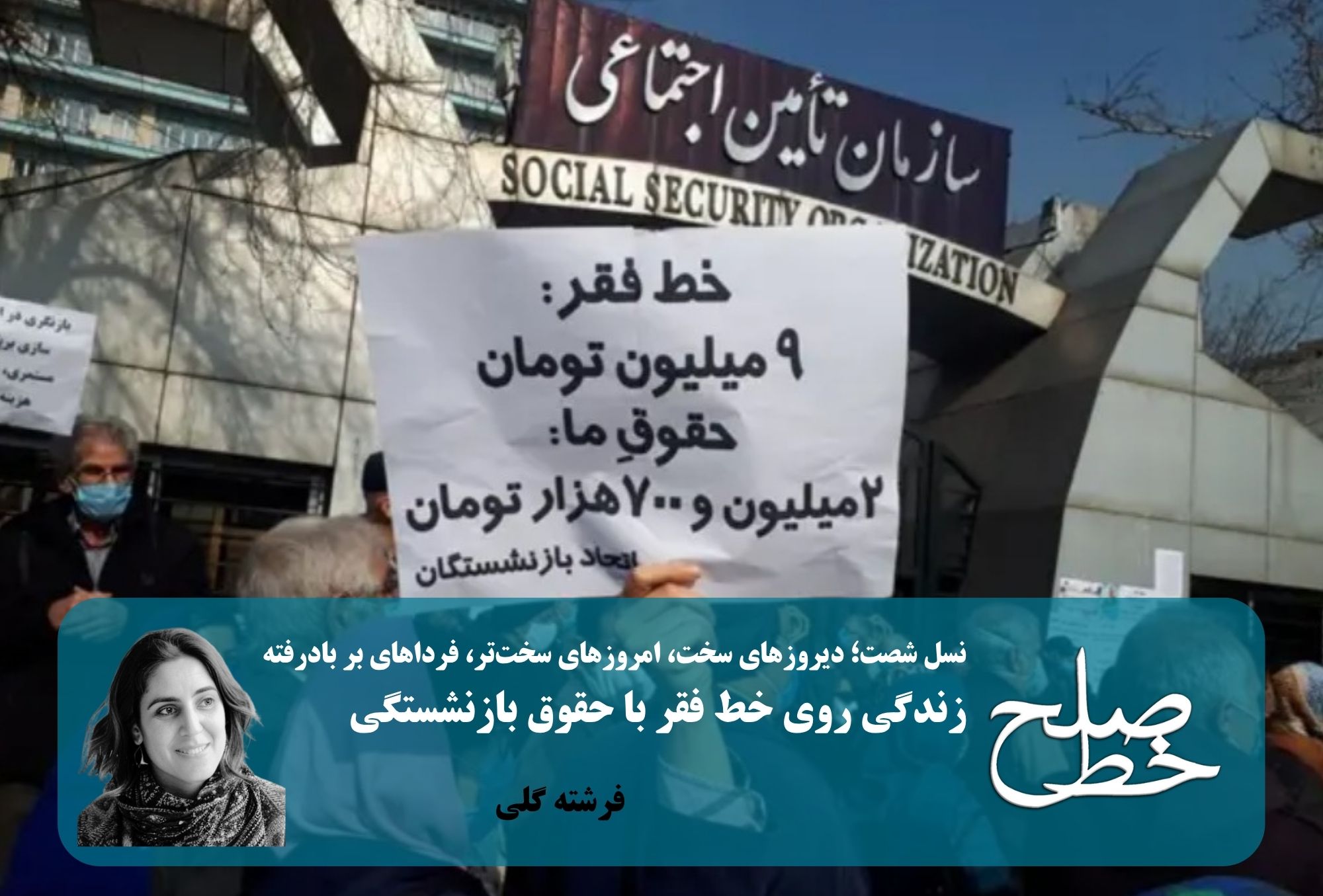

But what services are these funds supposed to offer their insured members? Their main obligations include paying retirement, disability, and survivor pensions, along with allowances such as marriage, healthcare, and funeral costs. Nevertheless, Iran’s pension system—especially the Social Security Fund—is facing deep structural challenges threatening its long-term survival. The roots of this crisis lie in the imbalance between financial resources and expenditures, driven by factors such as an aging population, high unemployment, inflated pensions, premium evasion, and lack of transparency. Misguided government policies have exacerbated these problems. The instrumental use of fund resources for goals like job creation or subsidy payments has often led to unprofitable investments and accumulated government debt to these institutions. Consequently, inefficient investment management has caused fund asset returns to fall behind the country’s rampant inflation rate, weakening the purchasing power of pensioners.

In recent decades, pension funds have reached a crisis state, and the Civil Servants Pension Fund is no exception. Despite some structural changes within this fund, its instability and management and financial challenges have steadily grown. According to official statistics, in 2023 (1402), the Civil Servants Pension Fund covered 841,020 contributors and 1,715,656 pensioners, resulting in a support ratio of just 0.49. The gap between insurance revenues (employee contributions) and insurance expenditures (pensions and related benefits) has steadily widened, reaching about eight times the revenue from contributions in 2022 (1401). This stark gap demonstrates the significant disparity between expenditures and revenues and underscores the fund’s increasing instability. In 2022, a large portion of the fund’s expenses was covered by government assistance, with only 15% of expenditures financed through received contributions. (1) These figures clearly reflect the severe unsustainability of the Civil Servants Pension Fund. The crisis stems from factors such as chronic mismanagement, adoption of support laws contradicting insurance principles, and vulnerability to unfavorable macroeconomic conditions. To overcome this crisis, three broad categories of solutions have been proposed: “process and operational reforms,” “administrative structural reforms,” and “parametric reforms.” However, some experts, citing the funds’ bankrupt state, consider the ultimate solution to be their closure and the undertaking of deep structural reforms.

Is closure the answer? The fund’s performance has shown that the Civil Servants Fund is a “financial black hole” for the government budget. Shutting it down and replacing it with a system based on individual accounts could, in the long run, relieve the government of this enormous financial burden. In such a scenario, the government would no longer need to allocate hundreds of thousands of billions of tomans annually from the public budget to cover its deficits, freeing up significant financial resources for infrastructure, healthcare, education, or debt repayment.

On the other hand, the fund’s continued existence as a “perpetual problem” has led governments to resort to temporary fixes (such as injecting money from other funds) instead of addressing the root issue. Shutting it down would force everyone to plan for a more sustainable, transparent, and equitable retirement system, ultimately creating a new system based on “defined rights” or “funded individual accounts” rather than “pay-as-you-go from the next generation.” The large, centralized structure of the Civil Servants Fund is highly vulnerable to administrative and financial corruption. A new, decentralized system with stronger oversight mechanisms could enhance transparency. Individuals would know exactly how much is in their accounts and how it is being invested, reducing the risk of fund misappropriation. The current system heavily favors older generations (who retired with higher support ratios) and disadvantages the younger generation (who must pay premiums with lower support ratios). Its dissolution could eliminate this complex and costly bureaucracy, resulting in administrative cost savings. However, these advantages are only valid in theory and based on overly optimistic assumptions. The real-world consequences of such a closure would be disastrous.

Let’s consider these consequences: millions of retirees, employees, and government workers who have financially planned their lives around the promise of receiving a pension would suddenly find themselves on the brink of absolute poverty. If the government violates its largest financial obligation (pension payments), no citizen will ever trust any government promise again. Furthermore, how can the government open accounts in a new system for someone with 30 years of premium contributions? This transition would be so complex and costly that it could itself trigger a new crisis. Finally, a fully individual-based system may work well for high-income earners, but low-income individuals or those with irregular work histories will face poverty in retirement unless strong redistributive mechanisms are built into the new system.

But there’s another looming threat that could soon confront these funds with an even more fundamental crisis: the entry of the 1980s generation into old age and retirement. The aging of this generation—those born in the 1360s (1980s)—is one of the most pressing challenges for Iran’s pension systems and social security funds. This demographic wave exerts immense pressure on both commitments (pension payments) and resources (insurance premiums).

The pressure on obligations (expenditures and payments) rises as more individuals reach retirement age. The economically active population paying premiums rapidly turns into a pension-receiving population. This dramatically reduces the support ratio, meaning fewer active contributors per pensioner. With longer pension periods—due to improved healthcare and increased life expectancy—the 1980s generation will spend more years in retirement, obliging funds to provide benefits for extended periods. As both the volume of payments and the number of pensioners increase, so does the total annual payout—exponentially. In the context of high inflation and rising pension rates, this places even greater strain on the system.

Another looming risk as this generation retires is the decrease in active contributors. Because of the large population size of the 1980s generation, their exit from the labor market represents the loss of a massive contributor base. Subsequent generations (such as those born in the 1990s and 2000s) are smaller in number and cannot fill this gap in fund revenues. Add to this the effects of weak economic and employment growth. If the economy fails to generate enough jobs, even the smaller future workforce may not be able to contribute adequately. High unemployment directly translates into declining fund revenues. Now add another factor: dependency on government budgets. Many funds (like the Civil Servants Pension Fund) have become reliant on direct government assistance to meet their obligations. This creates enormous pressure on the national budget and diverts resources that could otherwise be invested in healthcare, education, or infrastructure toward covering pension deficits.

To better understand the consequences and risks, consider the following:

Structural Deficit Formation and Deepening: In more precise terms, the combination of rising costs and falling revenues results in a structural budget deficit for the funds. This means that even under normal economic conditions, fund revenues do not cover expenditures.

Reduced Investment Capacity: Funds need to invest in profitable projects to grow their income. But when the majority of their resources go toward current pension payments, their long-term investment capacity diminishes, deepening the vicious cycle.

Threat to Timely Pension Payments: In the worst-case scenario, without structural reforms, funds may face liquidity crises and be unable to pay pensions on time. This could spark serious social unrest.

Strain on the Healthcare System: An aging population means increased demand for health services, much of which falls on health insurance funds, adding another financial burden.

In the end, the aging wave of the 1980s generation is like a “financial tsunami” heading toward Iran’s pension funds. This phenomenon has disrupted the traditional balance of the funds—originally designed for high fertility rates—and now poses an existential threat. Solving this problem requires immediate and comprehensive structural reforms, including raising the retirement age, adjusting premium rates, changing pension calculation formulas, expanding profitable investments, and adopting pronatalist policies. Without these reforms, mounting pressure on fund resources could lead to a severe financial and social crisis. However, given the country’s current circumstances—including sanctions, the reactivation of the trigger mechanism, hyperinflation, and structural governance barriers—it appears that there is neither the will nor the preparedness to implement such sweeping reforms. Thus, a low-cost resolution to this crisis seems unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Footnotes:

1- Review of the Status of the Civil Servants Pension Fund (Challenges and Solutions), Islamic Consultative Assembly Research Center, March 3, 2025 (13 Esfand 1403).

Tags

Elderly expensive Insurance Investment National Pension Fund Paragraph peace line Retirees Retirement Social Security Organization Swelling ماهنامه خط صلح