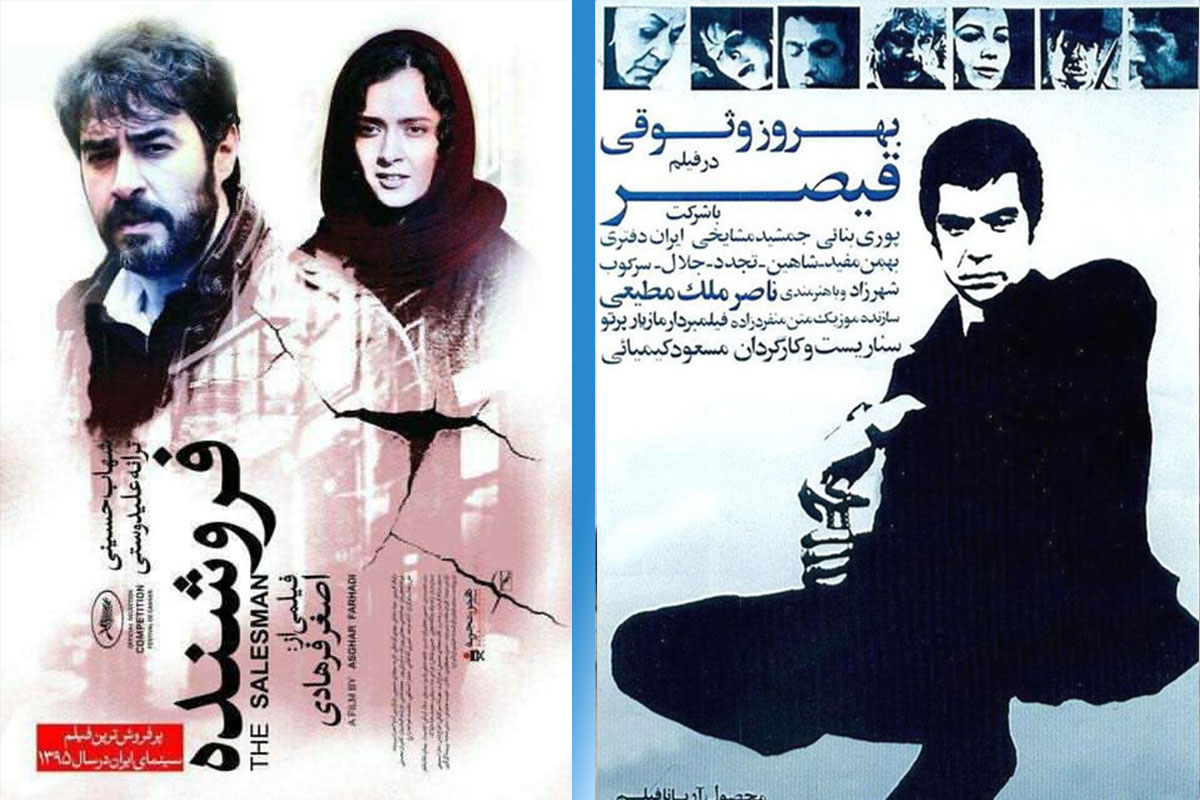

From Caesar Kimiaei to Farhadi the seller; Changing the image of women in Iranian cinema / Ali Ajami.

This is a caption.

Ali Ajami

In the span of half a century, Iranian society has undergone significant changes from the film “Qeysar” (1348) to “The Salesman” (1396). Comparing the portrayal of Iranian society in these two films can demonstrate these changes; however, this writing will focus on the changes that have occurred in the depiction of Iranian women in cinema, which may not necessarily reflect the real-life changes in the status of women in the world.

The selection of the two films, “Caesar” and “The Salesman”, was not a coincidence; both films have been popular among contemporary audiences, both directors have been the creators and narrators of the issues of their time, and most importantly, both films have a similar central story; the occurrence of a sexual assault and the attempt to achieve justice. Of course, this writing is not meant to be limited to just these two films.

In the movie “Caesar”, the story unfolds when the key is turned and Caesar’s sister reveals in her suicide note about a violation that has left her with no option but to take her own life. Caesar only thinks of revenge and it is only after taking revenge that he shows a victorious smile, indicating a sense of healing.

The woman in the film Caesar, after being raped, has no choice but to commit suicide. We don’t know much about the scene of the crime. But whatever has happened in the male-dominated society of Caesar, this shameful stain for his sister can only be erased through suicide and complete elimination, and for Caesar and the man in the story, only through revenge. In the society of Caesar, there is no other option for a woman who has been raped but suicide. There is no place in the film to express surprise or regret for Caesar’s sister’s action, and even Caesar’s revenge is only a temporary solution to the stain of dishonor and the death of his brother, and it cannot help his sister much.

In the story, the seller, Rana, is assaulted and the story is actually about how Rana and her husband confront this assault. The assault scene is not shown and we, like Rana’s husband, do not know exactly what happened until the end; we only know that Rana resisted and made noise, and after the assailant fled, she was taken to the hospital unconscious and with a broken head.

The comparison of Rana and Fatima makes it difficult, but the purpose of this writing is to compare the portrayal of women in cinema, not necessarily the situation of women. Therefore, as far as the depiction of women in cinema is concerned, this key difference is that Rana, unlike Fatima in the film “Qeysar”, does not see the need for suicide or complete elimination of herself to satisfy the honor of the male-dominated society and free herself from this shameful stigma; although she does not find a way to heal her personal pain, neither from her husband, nor from her family, nor from her friends, nor of course from the police, no help is provided.

Emad, in the same proportion, also faces a completely different confrontation with the story of assault; he cannot take revenge like Caesar, nor forgive and forget, and it is natural that the man has also changed in the same proportion. Gray people like Farhadi, unlike black and white chemical people, make forgiveness and revenge more complicated. Unlike the Mangol brothers, whose faces are even black and unempathetic, in the movie “The Salesman” we have a weak and abusive middle-aged man who can barely survive without his sublingual pills, and his impotent and pitiful character does not ignite the desire for revenge.

None of the women in the film “Qeysar” have a significant role and they are all heavily dependent on men even in their brief presence: the Mashhadi mother who is supposed to be taken to Mashhad by Qeysar, the fiancée whom Qeysar has named “Esme Royesh” and is now seeking revenge for her freedom, and the Russian woman who not only sleeps with Qeysar without payment, but also helps him find the address of the Abmangol brothers; determined and strong men and women full of requests and pleas; an idealized image of a man in a patriarchal society.

Contrary to Caesar’s women, saleswomen have more agency and are less dependent on men: Rana is a theater actress, a single mother who is also a director, and of course we see a woman similar to Caesar’s wife in the saleswoman; an older man who, in his only presence, sacrifices his manhood for his husband’s charity. Except for the saleswoman and the relationship between Rana and Emad, in other Farhadi films, these women are often the ones who are leaving and causing separation, not the men, and it is these men who must try to maintain the relationship; the most familiar example being the relationship between Simin and Nader in A Separation.

Chemical has said that Ali Shariati liked the film “Caesar” because he believed that “Caesar” was a “masculine” and “dynamic” film that had been taken out of work. With this perspective, it is likely that the seller of the film is not a woman, simply because women have more roles and agency, and there is no news of unattainable and determined men walking away from it.

Although cinema is not necessarily a reflection of society, by comparing the cinema of Kiarostami and Farhadi, it can be said that Iranian women, despite facing oppressive legal structures, including mandatory hijab, have been able to portray a better and more active image of their role, will, and agency in cinema. However, it should be noted that even though a woman may be a victim of assault and her abusive husband may appear to age with her in the final scene of the film, there is no sign of a victorious smile or indication of her liberation.

Created By: Ali Ajami

Created By: Ali AjamiTags

Actors of life Ali Ajami Asghar Farhadi Caesar Cinema Exceed Leadership Monthly Peace Line Magazine New movies peace line Salesperson Sexual assault Suicide