The Flawed Cycle of Books and Reading in Iran/ Reza Najafi

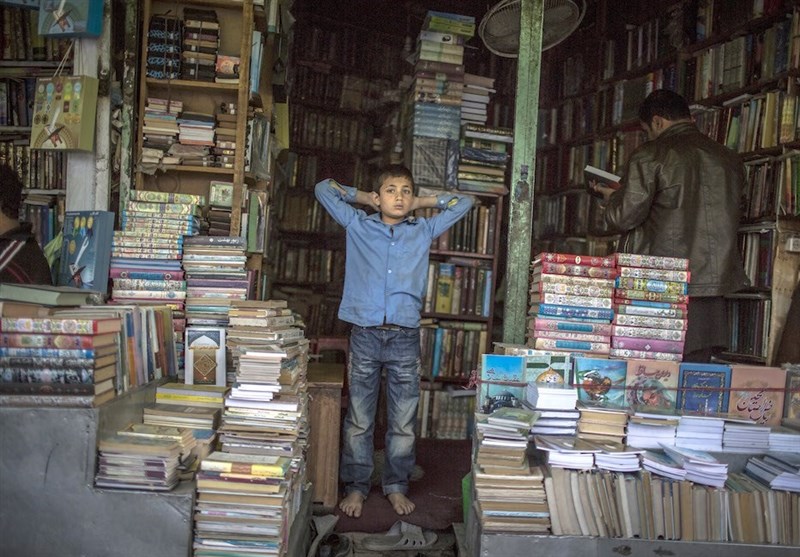

This is a caption

This is a caption

Reza Najafi

Even during Book Week and reading, we cannot forget the crisis that exists in this field. The difficulties of books and reading in Iran are not a hidden matter that needs to be proven, but what can be addressed are the roots of these difficulties and why the situation of books and reading in Iran is so unstable and who is to blame?

What are the four components involved in the existence of books, namely the people of the pen (including writers, translators, critics, and editors), publishers, readers, and ultimately government or ruling institutions. The writer of these lines believes that we cannot solely blame one or two factors, such as government institutions or people’s lack of interest in reading, but all four components play a role in the problems related to the phenomenon of books and reading. Of course, the shortcomings and misconduct of each component have not been without impact on the functioning of other components and have led to a vicious cycle. For example, the shortcomings of government institutions have a significant impact on weakening publishers, and an unsuccessful publisher also contributes to the failure of the people of the pen. An unsuccessful writer also produces an unsuccessful book, which in turn causes readers to shy away from reading. In any case, instead of insisting on proving whether the chicken or the egg came first, it might be better to accept that each side of the story

What is to come is examples to prove the writer’s claim, but what should be done or what can be done requires further opportunity and discussion; although in many cases, what can be done can also be found through the lines describing the roots of the problems.

Readers and cultural poverty

In the discussion of cultural poverty, we can mention various sub-branches and different points, but to avoid prolonging the speech, we will not go into further details and suffice to mention some generalities. One of the most important causes of cultural poverty is general illiteracy. A country where the average reading time is not more than a few minutes and after thirty years, the average number of copies of published works in this country is still only eighty million – and in the field of fiction literature, it does not exceed two thousand copies – how can we expect to compete with countries whose number of copies and reading rates are tens or even hundreds of times higher than ours? The common practice of publishing only two or three hundred copies of literary works in Iran should be considered a serious crisis in this area.

Mentioning a few examples sheds light on the dimensions of this tragedy. Annually, twenty-five thousand copies of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses are sold in Germany, fifty thousand copies of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, and thirty thousand copies of Thomas Mann’s novel Buddenbrooks. In just one year, over one million copies of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front were sold in the West. (1) When Hemingway entrusted his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls to be printed, despite the start of World War II and the focus of the world’s minds on this event, the mentioned work, which was related to a past event – the Spanish Civil War – sold only three hundred and sixty thousand copies in America in a short period of time.

Unfortunately, the main reason for the high number of literary works is not just the development of a country, just as underdevelopment cannot justify this problem. The reason for this claim can be seen by looking at the per capita reading rate in countries like Russia and Latin America. According to official statistics, even during its worst economic, social, and political periods, Russia maintained the highest per capita reading rate in the world for years. This enthusiasm for reading is not solely due to government policies and support, as evidenced by the rush to buy copies of the novel “Master and Margarita” by Bulgakov, despite government restrictions and obstacles. In one night, almost three hundred thousand copies of this novel were sold in the black market.

Unfortunately, the population number is not the only reason for increasing circulation. For example, the statistics of book readers and the per capita reading rate in countries like France and Germany, which have a similar population to Iran, are much more impressive than our country.

What was said – poverty of reading, weak circulation of literary works, etc. – inevitably leads to other consequences and not becoming a profession and not being economically viable in literary creativity. It is natural that with the usual circulation, fewer writers in Iran can devote themselves full-time and professionally to writing and have no concern other than writing. Based on this, as mentioned at the beginning, a vicious cycle of cause and effect is formed: low demand and audience for part-time and amateur writers and part-time writers creating less desirable works, which in turn increases the lack of attractiveness and value of works due to the lack of demand and poverty of reading. Based on this analogy, consider the impact of this process on the publishing industry, translation, research, editing, technical affairs, and related branches of publishing, etc.

How much work do Iranian writers do?

In addition to the reasons mentioned, the problem of cultural poverty in our country can also include the social problem of Iranian writers’ unemployment. Due to various psychological and sociological reasons, Iranian writers suffer from unemployment and lack of patience compared to their colleagues in other countries.

Not all the problems and dimensions of poverty can be solved by reading books. There are numerous examples where, despite the attractiveness of a work, the audience has been repelled and disinterested. At the very least, it can be argued that the value and attractiveness of a work relatively increases the demand for literary works. Perhaps it would be more beneficial for Iranian writers to accept their share of responsibility in this cultural damage instead of blaming readers and constantly accusing the general public, and solve at least part of the problem by improving the quality of their works. If we cannot find examples in our literature that are on par with War and Peace or The Old Man and the Sea, it is not solely the fault of Persian readers. Part of the issue is that we, as writers, do not have the perseverance, discipline, attention to detail, and hard work of authors like Tolstoy and Hemingway. It has been said that Tolstoy rewrote his two-thousand-page novel seven times

Non-professional publishers

Bitter irony is that the number of publishers in Iran is four times the number of bookstores; twelve thousand publishers versus three thousand bookstores.

Furthermore, the deputy of the Office of Book and Reading Development of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance of Iran has stated that among the total number of publishers who have publishing licenses in Iran, 7,529 publishers do not publish books.

This statistic shows that only thirty percent of publishers in Iran publish books, and out of this thirty percent, only nine percent are active. Unfortunately, the majority of active publishers are in the field of textbooks or popular works. Many publishers actually publish postcards and calendars. However, the number of inactive publishers in the country is significantly higher due to government subsidies, which have led many to obtain government paper and other benefits in order to obtain a publishing license.

Out of all these cases, it is rare to find a publisher who is knowledgeable about the book and printing industry in a professional manner. Of course, we have seen some progress in recent years, but the truth is that most publishers in the country do not have a strong background in the arts of page layout, graphics, cover design, etc. Most publishers in Iran are focused on the economic aspects of the publishing industry and are less willing to publish valuable works that may have a smaller audience. As a result, these publishers are even willing to publish worthless but popular works in order to make more profit. They are not very concerned about the quality of translation or writing of a work, as long as it sells well.

The number of publishers in Iran who obtain permission to print works from foreign owners (copyright) is also not as small as the fingers of a hand. It is obvious that this means unprofessional work; now imagine how unethical it is! A work that is published without respecting copyright is not guaranteed to be of good quality.

Iranian publishers rarely hire professional editors, consultants, critics, etc. and easily sacrifice the quality of their work for economic savings. Iranian publishers are rarely aware of the developments in the printing and publishing industry worldwide and still operate in a traditional and conventional manner. Many Iranian publishers not only do not have a publication to introduce and promote their work, but they are also unaware of professional websites and modern methods of communication. These publishers not only do not participate in any reputable book fairs around the world, but they also do not hold any book launch or review events themselves. It is not uncommon for publishers to not even read the books published by their own publishing house.

Many writers also point to the flawed and even mafia-like nature of the book distribution system, which is mostly controlled by some major publishers.

What was said was a handful, an example of the chaos in the non-professional sector of our country’s publishers, which if it were not for this, undoubtedly the state of books in Iran would have been a little better than it is now.

The role of government officials in the crisis of books and reading.

It is evident that censorship and inspection of works in Iran is the most destructive function of power institutions in the field of books. Due to this phenomenon, not only many books remain unpublished, but also many works are published with deletions and alterations, and in a distorted and incomplete form, which also creates a pessimistic attitude towards published works. It is often seen that readers assume that any book that has been licensed has definitely been published with deletions, alterations, and changes, and is not worth purchasing, solely due to the existence of an organization for monitoring publications.

The existence of an institution for auditing has also been problematic for other reasons in the matter of book publishing. Apart from subjective audits, the time-consuming and lengthy process of auditing and the administrative stages of obtaining a license have greatly affected the rights of the author or publisher, and they have lost the chance to timely release their book. This has also resulted in significant losses for the readers.

In the past, although there have been cases of negligence, laziness, neglect, wrong policies, strictness in printing and publishing, and overall negative aspects, there have also been times when government policies and support have had a negative impact. This means that non-expert support from some cultural officials for low-quality and weak works, the existence of government subsidies and monopolies, etc. have led to an increase in laziness among writers, the prevalence of unreliable works, and the neglect of more valuable works. This has disrupted the natural equations governing the printing and publishing market, discouraged stronger writers, driven away readers, and so on. In fact, in the final analysis, this type of non-expert support for weak works is considered an injustice towards the writers themselves, as it hinders their progress, apprenticeship, and experience, and ultimately prevents them from improving themselves and their works.

Lack of proper policies in our country’s education system to encourage students to read, lack of equipping the country’s library network, lack of support for bookstores, lack of support for writers, and dozens of other cases can be listed as the contribution of government institutions to the stagnation of the book market and reading.

Out of these numerous cases, only one example can be seen as a sample of the success, and that is the Tehran International Book Fair. Officials always proudly mention the organization of this fair and consider it as one of their successful actions in the field of books.

We pass by this point that we are not facing a phenomenon of exhibition, but a large store where people go mostly because of the ten or twenty percent discount, and we also pass by the fact that in the same large bookstore, the stands selling fried potatoes sell more than the stands of publishers, but the question arises that if the policy of offering discounted books at the international exhibition for the general public is a correct policy, why don’t they hold this charitable event on a seasonal or monthly basis instead of just ten days a year? And why not have a permanent exhibition? Why should it attract the entire country and people to one place, create traffic and commotion, and then close down for the rest of the year for three hundred and fifty-five days until those ten days arrive again, causing traffic and congestion once more!? What percentage of visitors to the Tehran Book Fair actually buy books and to what extent? How much of the success of the Tehran Book Fair is due to the absence and shortage of

And finally, in order to transform the mentioned square into a cycle, which is of course a futile cycle, other factors must also be added that play a role in the crisis of books and reading, which is not specific to our country; for example, the emergence of competitors such as social networks, the internet, films, computer games, etc.

Perhaps the weight of these factors in stagnating the book market is more than any other factor, but if there is a solution, that solution is primarily in maintaining and repairing the edges of the same square that we have discussed in detail.

Notes:

Schmitt, Reiner, The Life of Solitude Writers, translated by Mahshid Mir Moazami, Salis Publishing, p. 339

Farhangnia, Zahra, Death of Bookstores, City Book Magazine, August 2015

Seventy percent of Iranian publishers do not print books, the Persian version of the Middle East website, August 18, 2014.

Created By: Reza Najafi

Created By: Reza NajafiTags

Book Book and reading Bookstore Censorship Herman Hesse Monthly Peace Line Magazine Newsletter peace line Publishers Reading Reading rate Reza Najafi Tehran Book Fair