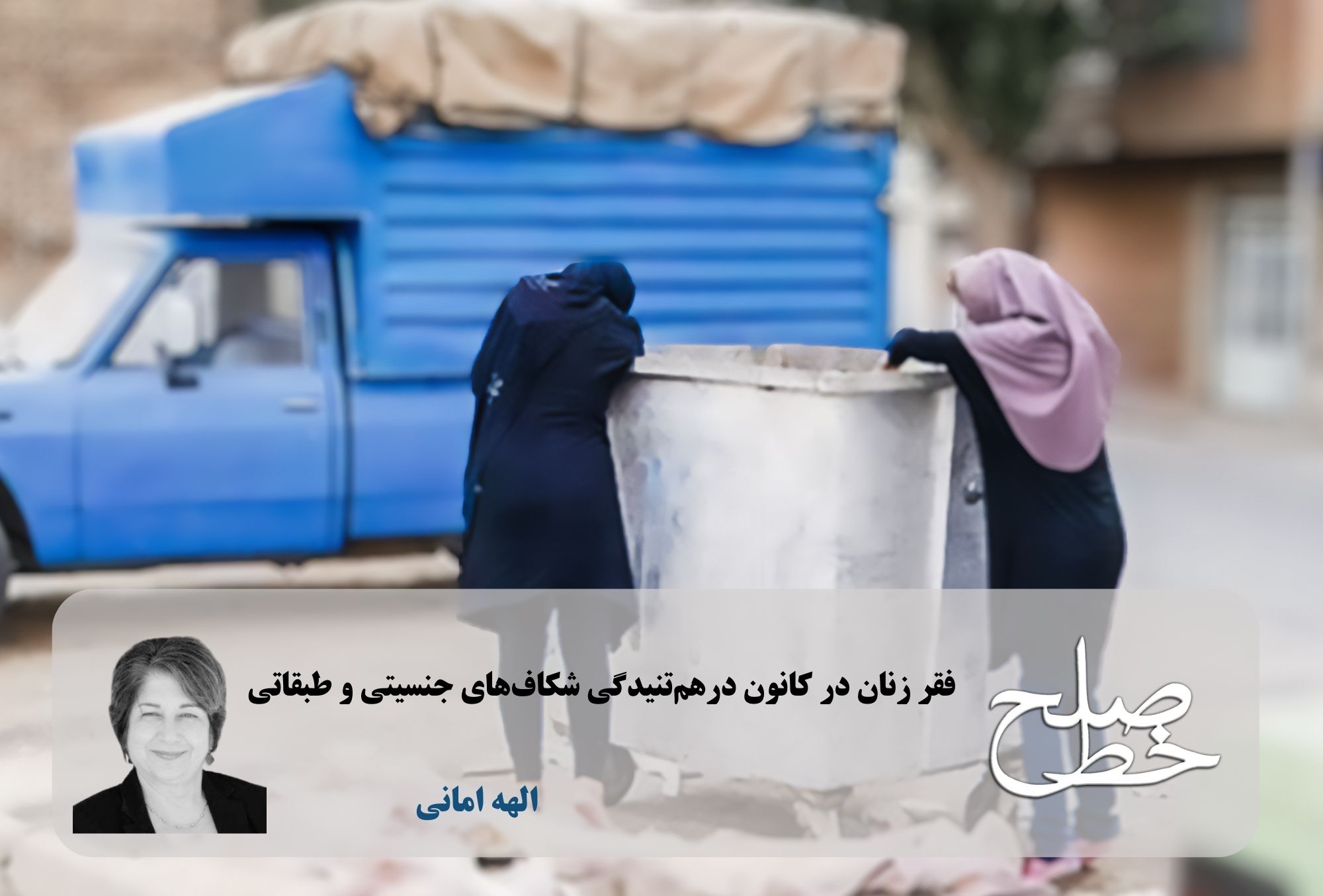

The Feminization of Poverty at the Intersection of Gender and Class Inequality/ Elahe Amani

In his 2020 speech at the “Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture” titled “Tackling the Inequality Pandemic: A New Social Contract for a New Era,” António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, offered strong criticism of neoliberal politicians and theorists. These were the same individuals who, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, claimed, under the slogan “We are all in the same boat,” that the crisis affected everyone equally and described the pandemic as a shared catastrophe. Guterres called this claim a “myth,” stating: “While we may all be floating on the same sea, some are in superyachts and others are clinging to drifting debris.” He added: “It’s often said that a rising tide lifts all boats, but in reality, increasing inequality sinks them all. Extreme inequality is associated with economic instability, corruption, financial crises, crime, and adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Discrimination, abuse, and lack of justice for many define inequality.” (1)

Rejecting such artificial notions of solidarity, Guterres emphasized: “It is a lie to say that the free market can provide healthcare for all, it is a fantasy to think unpaid care work is not real work, and it is delusional to claim we live in a post-racial world. The COVID pandemic shattered the myth that we are all in the same boat.” He outlined the UN’s vision: “Food, healthcare, water and sanitation, education, decent work, and social security must not be commodities that only the privileged can afford—they are human rights for all. We need a new social contract and a global agreement that guarantees equal opportunities for everyone.” (1)

In another speech titled “The Failure of the Neoliberal Paradigm” at the 78th session of the UN General Assembly (September 2023), Guterres warned: “A child’s fate seems to be determined even before birth, based on where in the world they are born and what social class their family belongs to—this dictates their life opportunities.” He argues that the legacy of neoliberalism is “a mass of deprived and marginalized people,” and that neoliberal policies are among the main drivers of today’s global inequalities. (2)

Today, inequalities are at the core of many global crises. The intersection of these crises forms a condition referred to as “polycrisis”: a state in which multiple, interconnected crises occur simultaneously, compounding one another and producing consequences greater than the sum of their parts. (3) In today’s world, the environmental crisis, the war in Ukraine, inflation and the high cost of living, the war in Palestine, climate change, gender inequality, global economic instability, and the rising humanitarian crises caused by poverty, conflict, and food insecurity—all interwoven—compose the current polycrisis.

The roots of many economic inequalities—whether in income or wealth distribution—lie in the processes of capital globalization and neoliberal structures, which have been exacerbated by the empowerment of multinational corporations and their immense interests. These inequalities are clearly reflected in global statistics. Today, 83% of countries experience very high income inequality, encompassing 90% of the world’s population. Wealth inequality is even more severe. From 2000 to 2024, the wealthiest 1% of the world’s population acquired 41% of all newly created wealth, while the poorest 50% received only 1%. During this period, the average net worth of someone in the top 1% increased by $1.3 million, while the net worth of someone in the poorest 50% rose by just $585. (4)

Social disparities are also sharply increasing. One in four people worldwide—about 2.3 billion—face food insecurity. (5) The income gap between countries of the Global North and South grew from $14,000 in 1960 to approximately $52,000 in 2023. Income inequality within many countries remains high or is worsening, a phenomenon tied to slower economic growth, political polarization, declining social mobility, and rising social tensions. Moreover, between 800 million and 1.1 billion people are projected to live in extreme or multidimensional poverty in 2025, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa, with significant numbers in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. (6)

In a world where economic inequality is rapidly expanding, the hopes for peace, prosperity, and gender or economic equality grow dimmer. The concentration of income and wealth at the top leads to a concentration of economic and political power, which in turn harms social cohesion. From the United States to Iran, from Bangladesh to Sudan, the fragility of daily life fosters a deep sense of injustice, erodes public trust in institutions, and fuels discontent and despair.

Contemporary societies face multilayered inequalities—related to opportunity, education, health, access to justice, and quality of social life. Social class, gender, caste, race, geographic location, and ethnic identity all compound these intertwined disparities. These inequalities persist not only between countries but within them as well and are structurally reproduced. Economic inequality both drives and results from other forms of inequality. Economic divides underpin disparities in education, health, political power, and social mobility, and intersect with gender, racial, and ethnic inequalities. These multidirectional relationships, shaped by policy, history, and social structures, enable economic inequality to both generate and reinforce other disparities.

Economic inequality leads to poor educational and health outcomes, diminished social mobility, and the political exclusion of low-income groups. It entrenches the deprivation of women, racial and gender minorities, and marginalized populations. At the same time, many economic inequalities stem from structural gender, racial, and social injustices. Discrimination in the labor market, wage disparities, limited career advancement, housing and credit discrimination, and unjust economic policies all contribute to deepening class divides. Social, political, and economic structures perpetuate cycles of privilege and deprivation across generations. Policies such as improving educational equity can reduce social and economic disparities, but cultural and structural discrimination can persist even in more egalitarian societies. Ultimately, economic inequality is an inseparable part of complex social and political systems. Reducing it requires a fundamental rethinking of the policies, structures, and narratives that portray inequality as natural, inevitable, or even desirable. Understanding these interwoven structures is the first step toward building a more just world.

Political Economy and Gender: How Class Inequality Becomes Gendered

Class inequality in contemporary societies is not merely an economic issue; it is profoundly gendered, reproduced through the intersection of markets, governments, and social relations. A political economy analysis through a gender lens reveals that class inequality cannot be understood without addressing gender. Women not only have less access to income and resources but are also enmeshed in networks of discrimination and power dynamics that make their poverty deeper and more enduring. From this perspective, class and gender inequalities exist in a dialectical relationship, each reinforcing and reproducing the other.

Theorists such as Nancy Fraser and Silvia Federici have shown how neoliberal policies—through privatization, cuts to public services, and labor market deregulation—place women in more vulnerable positions. Women, particularly working-class and ethnic minority women, are the first to be harmed by social budget cuts and the last to benefit from economic growth. In the labor market, class divisions are closely tied to gendered labor divisions. The concentration of women in low-paying, informal jobs; wage gaps; insecure contracts without union protection; and overt and covert discrimination in career advancement all reinforce structures that accumulate wealth and power for the upper classes at the expense of working-class women. (7)

The Feminization of Poverty: A Structural, Not Individual, Phenomenon

The term “feminization of poverty” refers not only to the rising likelihood of poverty among women but also underscores the structural nature of the phenomenon. Women’s poverty is not a result of individual choices but is a direct consequence of patriarchal economic policies, legal discrimination, the unequal division of care labor, and the lack of state and social safety nets. In Iran, female-headed households, rural women, marginalized women, and Afghan migrant women are particularly exposed to structural poverty.

Care Work: The Hidden Economy and the Class Divide

Production/Reproduction Dichotomy: The formal economy focuses solely on the production of goods and services, but gender equality advocates emphasize that without social reproduction—including childcare, eldercare, patient care, and household management—the labor market could not function at all. The bulk of this essential, invisible, unpaid work is performed by women without any legal support.

Class Implications: When the state fails to provide adequate care services, the burden falls on lower-income women. While middle- and upper-class women may outsource care work, it is typically passed on to low-wage women workers. Thus, class divides are reproduced not only between men and women but also among women themselves.

Intersectionality: Multilayered Oppression and Inequality

According to Kimberlé Crenshaw, professor at UCLA and the originator of intersectionality theory, not all women experience inequality in the same way. Women may simultaneously face disadvantages related to class, ethnicity, migration, age, religion, gender identity, or urban marginalization. These intersections make poverty and inequality more complex and profound for some women. For example, a Baluch working woman or an Afghan migrant woman in Iran may experience poverty as a simultaneous gendered, ethnic, and class-based oppression. (8)

Class Divide, Patriarchy, and Structural Violence

Gender-based violence cannot be analyzed separately from class structures. Research shows that poverty and inequality increase women’s financial dependency on men, which heightens the likelihood of domestic violence. Poor women have the least access to legal, protective, or shelter services. Thus, the class divide not only reproduces gender violence but institutionalizes and perpetuates it.

Why Class Justice is Impossible Without Gender Justice

Closing the gap in economic inequality is impossible without transforming gender structures. Key policies in this area could include gender-responsive budgeting, expansion of public care services, reforming inheritance and property laws, securing rights for women workers, recognizing care work in social security systems, and strengthening women’s unions and organizations. Ultimately, class and gender inequalities are not separate phenomena but are historically and structurally interconnected. Women—especially working-class women—are at the intersection of these two forms of inequality. Therefore, any project aimed at social justice, whether national or global, will be ineffective without gender-responsive analysis and policymaking. As the saying goes, it would be like “pounding water in a mortar.”

Gender and Class Inequality in Iran

The crisis of poverty and class inequality in Iran has, in recent years, entered a structural and multidimensional phase, in which economic forces, political factors, and restrictive gender laws are intertwined—placing the heaviest burden on women, especially those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Iran’s class divide is not only a result of inflation, stagnation, and declining economic growth but also stems from factors like the expansion of the informal sector, weak social policies, gender discrimination in the labor market, and an inefficient redistribution system. The consequences of this crisis are particularly severe and layered for women due to their unequal position in the structures of family, market, and state.

Iran’s financial system itself is one of the arenas where economic inequality and class divide are reproduced. Thousands of financial institutions exist—more than half operating without licenses—pushing the economy toward risky and informal activities. Women, who historically have had less access to formal credit, bank loans, and support networks, are particularly vulnerable.

The labor market reflects similar patterns. While the unemployment rate dropped to 7.6% in 1403 (2024–2025), this improvement is largely due to people leaving the labor force altogether. Although the population over age 15 increased by more than 800,000, only 300,000 new jobs were created, and over 75% of new entrants to the labor market neither found work nor even sought it. This situation, particularly affecting women and youth, reflects deep despair regarding employment opportunities.

Women’s economic participation remains just about one-fifth of that of men, despite women making up half the working-age population. A key gendered dimension of this crisis is the high concentration of women in the informal sector. Of the roughly 3.6 million employed women in Iran, more than 2 million—nearly 57%—work in informal jobs. The informal sector lacks minimum wage protections, workplace standards, mandatory insurance, and benefits like paid leave or bonuses. Women are more vulnerable to exploitation and insecurity in this space than men—especially as they already face structural discrimination in the formal job market.

The lack of research on women in the informal economy is itself a serious challenge. A 1403 (2024–2025) study by Zeinab Moradinejad is one of the few that documents the lives and experiences of women in the informal sector, showing how this “invisible army” labors without protection in an exhausting and unsustainable system. (10)

Even in formal employment, deep inequalities persist. Although 45% of women have specialized education, only 4% occupy managerial positions, and women make up just 16% of all managers in the country. (11) The main causes include the heavy burden of domestic care, family responsibilities, and employers’ gender-based biases—especially in the private sector, where men are often preferred over women in otherwise equal circumstances. These trends intensify during times of economic crisis, sanctions, or global shocks like the pandemic, driving more women into informal or low-quality jobs. Currently, 83% of small enterprises (with fewer than ten employees) hire women, and most of this employment is informal and unsupported. (12)

The precarious nature of women’s employment is also visible in insurance data. While 75% of women work in the private sector, only 27% are covered by formal insurance. (12) This vulnerability became evident in summer 1404 (2025), when women’s employment suddenly plummeted following a 12-day war, revealing just how sensitive women’s labor markets are to economic shocks and how lacking they are in protective mechanisms.

The class dimension of this crisis is equally significant. According to the Iranian Parliament’s Research Center, the poverty rate stabilized at around 30% from 1397 to 1403 (2018–2024), meaning 25 to 26 million Iranians live below the poverty line. (13) Given persistent inflation, economic stagnation, and declining purchasing power, this figure is likely even higher. At the same time, over 95% of labor contracts are temporary. (14) This means the vast majority of workers—especially women workers—are denied job security, stable insurance, and the ability to plan long-term. Coupled with the housing crisis and rising education and healthcare costs, even the basic social reproduction of the labor force is becoming difficult.

This burden is even heavier for female-headed households, marginalized women, rural women, and Afghan migrant women—who sit at the intersection of class, gender, ethnic, and migration-related discrimination.

Together, these factors reveal that poverty in Iran is, above all, feminized. Economic inequality and gender discrimination reinforce one another in a vicious cycle. Women from lower classes bear the brunt of this crisis but have the least influence on policymaking and receive the least support. Until economic and social policies are designed through a gender-responsive lens, no poverty-reduction, class-justice, or human development strategy will succeed.

–

.

.

.

.

Tags

Class division Elahe Amani Gender discrimination 2 Gender gap Goddess Amani Layers of sediment Lowland peace line Poverty of women ماهنامه خط صلح