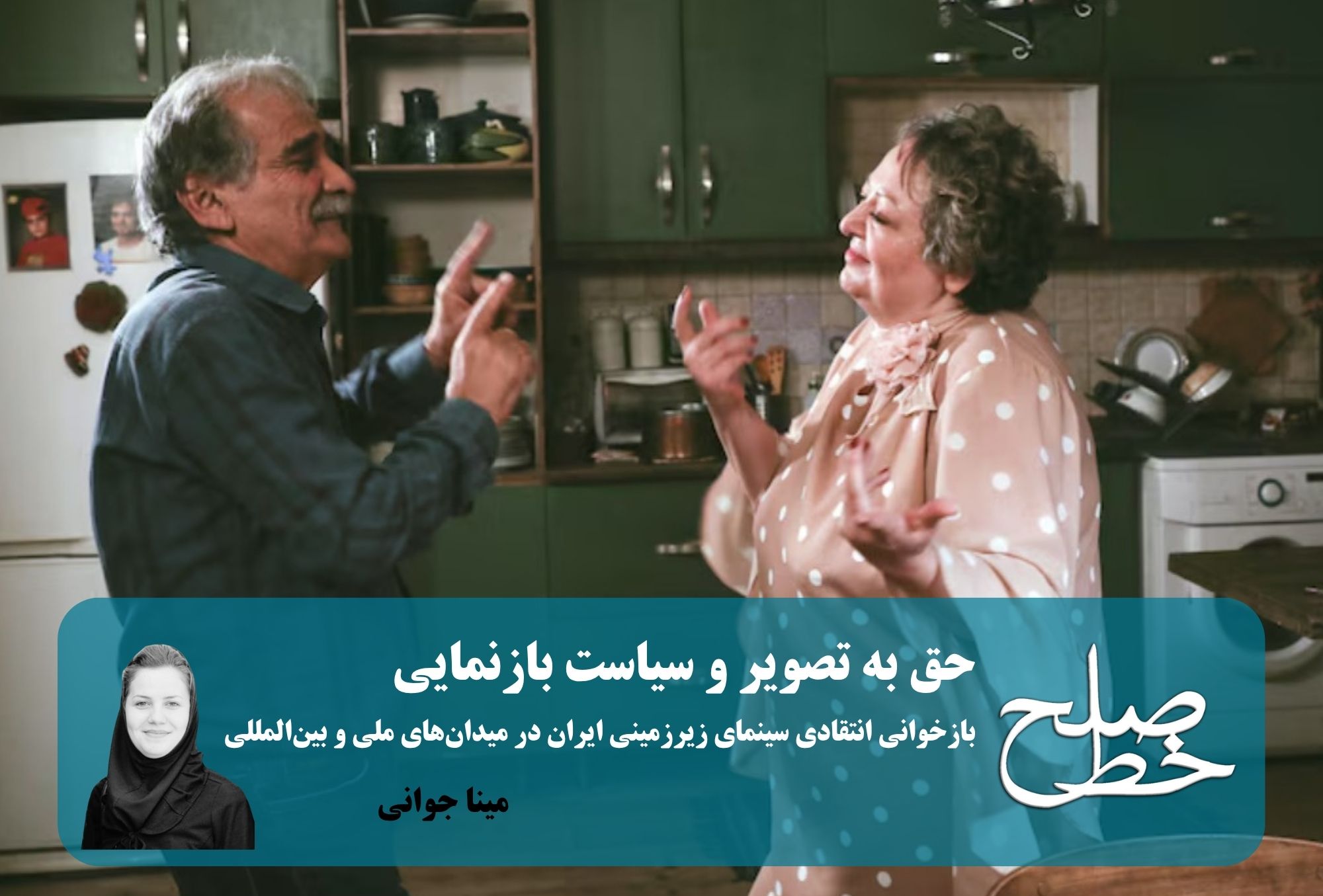

The Right to Image and the Politics of Representation/ Mina Javani

Iran’s underground cinema, as a semi-independent and often marginal sector of the country’s film production, has consistently navigated the intersection of legal restrictions, cultural pressures, and media representations. These films, produced outside the official mechanisms of Iranian cinema, not only provide a platform for expressing real social and ecological experiences, but also serve as vehicles for critiquing dominant cultural and political structures. However, the modes of representing these works—whether at the national or international level—rarely occur neutrally; they are always entangled with power-driven frameworks, audience expectations, and media policies.

Analyzing the representation of Iranian underground cinema requires a critical approach that, on the one hand, examines how meaning and imagery are produced domestically, and on the other, considers how international narratives are shaped. On the national level, these works face censorship and limited audience access, forcing filmmakers to adopt creative forms and languages to convey their messages. Internationally, representations of these films in festivals and media are often influenced by Western discourses and Iran’s broader visual politics. This essay aims to critically examine the differences, intersections, and tensions between internal and external representations of Iranian underground cinema and to demonstrate how these works can simultaneously function as tools of cultural resistance and as symbols of global image-making about Iran.

Representation of Iranian Underground Cinema at the National Level

Despite being produced on the margins of official structures, Iranian underground cinema has consistently acted as a critical space against the country’s cultural and political hegemony. These works, made outside of legal and institutional frameworks, face a wide range of restrictions—from direct censorship, film bans, and prohibitions on public screenings, to informal pressures such as threats to artists and social isolation. These constraints not only complicate film production but also shape the conditions of representation at the national level. Official media largely ignore these films, compelling filmmakers to create alternative pathways to visibility—a mechanism that itself signifies cultural resistance against hegemonic control.

In this context, underground cinema focuses on representing social and ecological experiences of Iranian society that have been marginalized within the official cinematic narrative. Domestic audiences primarily access these works through social media, private screenings, and digital distribution. This process has led to the formation of an “informal viewing community” that engages with the films by analyzing and reinterpreting them—sometimes even redefining their meaning. From the perspective of representation theory, this process illustrates that meaning is always produced in the interaction between text and audience, and that formal restrictions cannot fully prevent the emergence of meaningful experiences for viewers.

Another prominent feature of underground cinema is its formal and linguistic innovation in the face of restrictions. Rather than stifling creativity, censorship and prohibition have pushed filmmakers toward nonlinear narratives, visual symbolism, thematic coding, and metaphorical structures. These strategies are not only practical responses to censorship but also serve as implicit critiques and acts of cultural resistance. In other words, limitations have become catalysts for rethinking national identity, critiquing power, and producing meaning. From this angle, underground cinema functions as an active space for examining social tensions and structural contradictions in Iranian society.

Thus, underground cinema should not be viewed merely as a product of restriction, but as a platform for representing cultural policies, identity challenges, and social resistance. By depicting suppressed and marginalized experiences, these works enable domestic audiences to see themselves in the process of representation and to develop critical awareness of their current condition. From this perspective, Iranian underground cinema simultaneously reflects social realities and offers a critical reconsideration of cultural, political, and media hegemony at the national level.

International Representation of Iranian Underground Cinema

Iranian underground cinema encounters a different representational framework at the international level. These films—while facing extensive legal restrictions, censorship, and social pressures domestically—are recognized at global festivals and in international media as examples of cultural courage and resistance. Festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, and Venice not only provide visibility for these works, but also play a decisive role in shaping global perceptions of Iran and its cinema. However, these representations are often influenced by Western assumptions and discursive frameworks, tending to portray Iran as a repressed and restrictive society—a portrayal that may overlook the true social, cultural, and artistic complexities.

This contradiction between domestic experience and international representation is a key point for critically analyzing underground cinema. Inside Iran, these films often focus on daily life, social conflicts, and individual constraints, producing their meanings through engagement with domestic audiences. These audiences, using social media, private screenings, and digital distribution, reinterpret the films and help reproduce cultural and social experiences. But at the international level, such experiences are often framed as symbolic narratives of resistance and repression—a process that both facilitates visibility and reduces the films to cultural commodities for global consumption. This illustrates the tension between meaning production within the country and its reproduction on the global stage.

International festivals play a complex role in representing underground cinema. On one hand, they provide films with access to broader audiences and professional critique, helping to elevate filmmakers. For example, the works of directors such as Jafar Panahi and Mohammad Rasoulof—although heavily restricted in Iran—have been internationally acclaimed as examples of bold and independent cinema. On the other hand, festival and media representations tend to focus on the political, repressive, and restrictive aspects, thus placing the films within a limited and predictable framework. This process can result in simplification and even stereotyping of Iran’s image, where the societal complexity, cultural depth, and artistic creativity of the filmmakers are overlooked.

Beyond festivals, international media and critical reviews also play a significant role in shaping the global image of Iranian underground cinema. Reviews and media coverage—whether in specialized film publications or in general news outlets—often analyze the films through predetermined political and social discourses. Such analyses can reproduce an image of Iran as a repressed and constrained society, even when the films themselves focus more on ecological experiences and human relationships. This contradiction reveals that underground cinema, despite its critical and creative nature, is also shaped by global representations that sometimes distance it from its original complexity.

Nevertheless, international representation also offers important benefits. Foreign festivals and media not only enable these works to be seen, but also expand the space for dialogue and critique on social, cultural, and political issues in Iran. This representation can amplify the independent voices of artists and draw global attention to human rights, censorship, and freedom of expression. From this perspective, Iranian underground cinema becomes a dual-purpose tool for both domestic resistance and global critical representation. A critical analysis of international representation reveals that underground cinema occupies a dual position in the global context: as both a tool for creative visibility and a symbol of cultural and political stereotypes. This complex position suggests that a critical analysis of underground cinema must go beyond examining the films within the country; it must also consider the interplay between domestic experience, official restrictions, and global representation. Ultimately, Iranian underground cinema is more than artistic production—it is a space for analyzing cultural tensions, power, and global image-making, and its significance lies in understanding the relationship between art, politics, and cultural representation on a global scale.

Representation, the Right to Image, and the Tension Between the National and International

Simultaneously examining national and international representations of Iranian underground cinema reveals a discursive field of contradictions in which meaning, power, and image are in constant conflict. Nationally, underground cinema is a struggle to reclaim the right to speak and be seen. The filmmaker, in resisting censorship, emphasizes the “right to image” as a form of the right to exist in public spaces—through depictions of daily life and suppressed experiences. This right, which emerges from feminist and postcolonial theories of representation, implies the visibility of marginalized subjects in the collective field of vision. In Iran, underground films often center these erased subjects: women, ethnic and religious minorities, and the younger generation, suspended between law and lived experience. From this viewpoint, underground cinema is not merely an art form, but a demand for the right to citizenship and bodily autonomy.

However, at the international level, this very right to image is exposed to a kind of semantic appropriation. Films created in Iran to reflect specific social realities are often reduced in foreign festivals and media to symbols of political protest or resistance. This type of representation—while seemingly amplifying silenced voices—can, in practice, diminish the right to image by transforming it from a personal and cultural right into a utilitarian political tool. In this process, the image of Iran is frequently reproduced within a predetermined framework: a repressed nation, a society trapped in tradition and authoritarianism, and an artist cast as a heroic dissident. Thus, the right to image in global discourse is not rooted in the Iranian subject’s self-expression but shaped by the desire to view the “forbidden other”—a gaze that is constantly vulnerable to cultural colonialism and the visual politics of global powers.

Nationally, the right to image is linked to cultural resistance and self-expression, while internationally, it can become a tool for reproducing Orientalist discourse. This contradiction is evident in the differing aims and audiences: in Iran, underground cinema speaks from the society and to the society; abroad, the same work is read as a document of political and cultural oppression. From the perspective of representation theory, this distinction reveals that meaning is constructed at the moment of reception, and each discourse produces its own subject. As a result, Iranian filmmakers must navigate two discourses: resisting internal censorship while simultaneously resisting a form of cultural consumerism that seeks images of the victim or the exile.

From a human rights perspective, this duality shows that the right to image is not merely the freedom to produce content, but also the right to be seen fairly and without stereotype. The issue, therefore, is no longer just censorship or prohibition, but the nature of the gaze and the valuation of the image. Nationally, power prevents images from emerging; internationally, power possesses them through specific discursive frameworks. In both cases, the right to image is at risk—either denied or stripped of its meaning. The role of cultural critique, then, is to rethink the possibility of responsible representation—one that serves neither official politics nor the desires of a Western gaze.

In this context, the Iranian underground filmmaker occupies a dual position: seeking the freedom to express while also compelled to reconsider the ethics of the image. How can suffering, discrimination, or limitation be represented without reproducing a colonial gaze or victim-centered aesthetic? The answer lies within underground cinema itself: in its choice of indirect forms, metaphorical narratives, and the use of imagery as a coded language. This approach is not only a strategy to escape censorship, but also an effort to preserve the dignity of the subject in the image—to recognize the person as a rights-bearing agent in meaning production.

From this angle, Iranian underground cinema exists at the intersection of right and representation, resistance and consumption. Nationally, it acts as a cultural and political response to the denial of image rights; internationally, it risks becoming a visual commodity for global consumption. A critical analysis of this situation reveals that underground cinema, beyond being an artistic sphere, becomes a battleground over human rights, image ownership, and cultural agency. Only through this critical lens can we understand that representation in Iranian underground cinema is not merely a reflection of reality—but part of the struggle over who gets to define that reality.

Epilogue

In recent decades, Iranian underground cinema has become one of the most important arenas for confrontation between power, representation, and rights. This cinema has emerged not only in response to domestic censorship structures, but also as a space for rethinking the concept of image and human rights. At its core lie fundamental questions: Who has the right to be seen? Who can speak of suffering or freedom? And to what extent can an image carry truth without falling into the logic of power or consumption?

An analysis of both national and international representations of this cinema reveals that—despite their apparent opposition—both operate within a shared field of power and meaning. Domestically, the erasure of image is a denial of the right to presence; internationally, the presentation of the image within predetermined frameworks can become another form of erasure. In both cases, the central issue is the right to image—a right tied to both freedom of expression and human dignity. This right is not limited to production; it is defined by the conditions of viewing, the ethics of spectatorship, and the manner in which the subject is reflected.

From this perspective, Iranian underground cinema must be understood as a form of image politics—a politics in which every frame, every silence, and every body becomes a site of negotiation between visibility and invisibility. By avoiding direct representation and leaning on metaphor, silence, and brevity, this cinema creates an aesthetics of resistance—a resistance not only to censorship, but to the global appetite for consuming the image of the “other.” In other words, in its encounter with the world, underground cinema uses image as an ethical shield to preserve the dignity of the Iranian subject before the invasive gaze of the outside.

Ultimately, the significance of this cinema lies not only in the courage of its filmmakers but in the specific kind of awareness it produces: an awareness of the boundaries between freedom and representation, between truth and spectacle, between rights and power. In a world where image has become both weapon and commodity, Iranian underground cinema, by emphasizing the right to image, reminds us that to see and be seen is itself a political and ethical act. Thus, this cinema belongs not to the margins, but to the heart of the contemporary question of the human, the body, and freedom—a question that begins anew with every appearance of a forbidden image.

Footnotes:

Bordbar, K., & Monadi, A. (2025, July). A history and a film: On My Favorite Cake. Offscreen, 29(7).

Jahed, P. (2014). Underground cinema in Iran. Film International, 12(3), 106–111.

Karimi, P. (2025). Rebels with a camera: Critical zones and the aesthetics of Iran’s underground cinema. In Cinema Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation.

Khosravi, H. (2023, Winter). Iran’s cinema of resistance: Independent filmmakers offer a vital portal into the struggle against the theocratic regime. Dissent Magazine.

Tags

"Seda va Sima" translates to "Voice and Vision" in English. Censorship Cinema Fajr Film Festival Mina Youth New movies peace line ماهنامه خط صلح