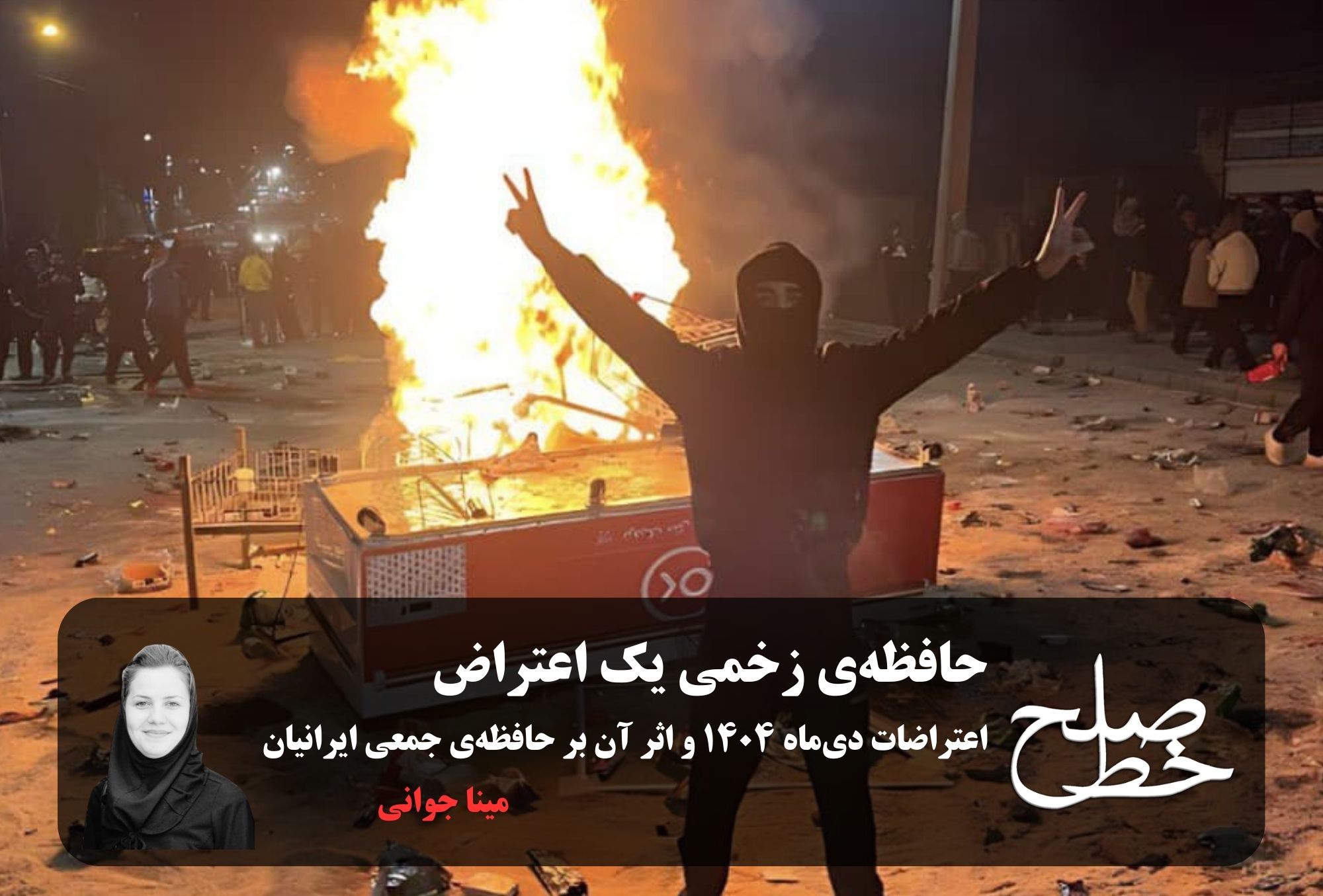

The Wounded Memory of a Protest/Mina Jawani

The protests of January 1404 are remembered neither as a single image nor as a narrative that can be easily retold. What remains is more of a scattering: unfinished scenes, videos that were cut short, streets that emptied sooner than expected. They neither became a moment of triumph nor a complete defeat; they remain in the collective memory of Iranians in a state of suspense between hope and exhaustion, a memory that still does not know what to do with the experience. This suspense is not simply a consequence of the protests being suppressed or subsided, but rather the way in which they became simultaneously a widespread lived experience and an impossible narrative. Although the protests emerged from livelihood crises and economic discontent, they quickly moved away from a purely causal logic and into a realm where the main issue was not the “why” of inflation. What was challenged was not simply economic policies or executive structures, but the relationship of society to government, to the possibility of collective action, and to the future horizon.

From this perspective, January 1404 can be seen as a moment in which familiar patterns of politics were once again disrupted. The street, as the main arena of political action, neither fully retained its position nor was it completely emptied of meaning; it was placed in a state of suspension. The consequence of this situation was the displacement of politics into other forms of struggle and resistance: from refusal and withdrawal to the politics of everyday life. This transformation cannot be understood simply as a retreat or defeat, but rather as a sign of the reconfiguration of politics in conditions of institutional blockage, social erosion, and the limitation of collective horizons. In such a context, these protests led to the production of a kind of wounded memory; a memory that has not been able to be collectively mourned and whose official narrative has been either blocked or marginalized. This memory, however, is neither passive nor silent; Rather, it returns as scattered signs in images, language, bodies, silences, and the social imagination, playing a role in shaping future ideals, expectations, fears, and modes of political action.

Focusing on these protests as a memory-making moment, this article attempts to examine their long-term social and political consequences; consequences that can be analyzed not in terms of immediate results or short-term developments, but rather in the way this experience is recorded, erased, and returned to the collective memory of Iranians and in the transformation of the horizons of political action and imagination.

The January 1404 Protests as a Memory-Making Situation: The Disruption and Reconfiguration of Political Action

If we analyze these protests not as a closed and measurable event, but as a memory-making situation, we can more accurately explain their impact on the collective experience and political perception of Iranians. Collective memory, in this context, is not a simple product of the accumulation of individual memories, but a dynamic and interactive process that operates between lived experience, official narratives, and forms of forgetting. In such a field, January 1404 was placed in a state of suspension between registration and deletion; a state that neither the official narrative could contain it nor absolute forgetting could erase it. This suspension fundamentally determines the quality of memory of these protests and distinguishes them from past protest experiences.

One of the determining factors in the formation of this unstable memory was total repression. Repressive measures, including restrictions on street presence, direct violence, and control of media content, not only stopped collective action, but also prevented the consolidation of public narratives and the formation of myths of resistance. As a result, protests became a series of “unstable moments”: short-lived street presences, images and videos that were quickly deleted or censored, and voices that were silenced before they could be consolidated. This instability was not a sign of the movement’s weakness, but a product of structural repression.

The memory of January 1404, in this context, is a wounded and pragmatic memory. Unlike established narratives, this memory does not function by retelling the past but by regulating expectations, fears, and modes of future political action. In other words, what remains is not the event itself, but the limitations, interruptions, and possibilities that it revealed. This very characteristic makes the impact of these protests unmeasurable in the short term; its consequences can be analyzed in the formation of new sensitivities, the redefinition of the costs of action, and the emergence of invisible forms of resistance.

This situation also reflects the reconfiguration of politics in contemporary Iran. Politics no longer necessarily occurs on the street or in the form of inclusive actions; it is transferred to the surface of the body, everyday life, silence and refusal. In this sense, Diya 1404 is an experience that simultaneously redefines memory and politics: repression, incompleteness and dispersion are both the constraints and the engine of the formation of a new kind of collective action. Collective action in this framework operates not in an overt cry or demand, but in the underlying layers of social time and dispersed memory.

This article then shows how such memory produces long-term social and political consequences; consequences that can be studied in the rearrangement of political action, the changing relationship between society and power, and the transformation of the collective imagination in contemporary Iran.

Long-term social and political consequences: Amidst repression and collective re-creation

The January protests were more than a momentary economic or political movement; they were a scene where organized violence and total state repression not only limited street action, but also affected the collective memory and political imagination of society in an unprecedented way. By restricting public spaces, direct confrontation, and cutting off and severely controlling the flow of information, security forces eliminated many moments of collective action before they could be consolidated. The result was an experience that neither became an official narrative nor was it completely forgotten; rather, a fragmented and scarred memory was created, the effects of which can be seen in society’s behavior, perception, and political imagination.

One of the most striking consequences of these protests is the production of a new logic of struggle. These new forms of resistance range from active refusal and limited speech to the careful regulation of presence in public spaces and the focus on underground networks. Such actions have the capacity to create resilient and resistant networks that, in the face of future constraints, can become new structures of collective action. Thus, state violence not only impeded current action, but also created space for the emergence of new and underground action in the long term.

The second consequence is a redefinition of society’s relationship to power and formal institutions. The experience of facing repression has reduced public trust and rebuilt the perception of the possibility of change. Society will learn that collective politics in conditions of threat is between action and caution; neither absolute passivity nor the reproduction of power, but a deliberate and cautious combination that, even in the absence of mass gatherings, can shape new forms of resistance.

The third consequence is the birth of a new political sensibility and imagination. A fragmented and wounded memory has recorded a network of suspended events, silences, and limitations that both solidify the restrictions imposed by the state and allow for the emergence of new action and innovative strategies. This memory will expand the horizons of the political and social imagination in the future, helping society to design different strategies to confront blockage and repression: a focus on the everyday, active refusal, and scattered but liberating actions.

The fourth and complementary consequence is the strengthening of civil society and the capacity for collective organizing. Wounded and scattered memory, while recording the limitations and violence of the state, also provides a space for practicing and redefining collective action. By demonstrating how to confront repression, the collective experience of December has activated underground networks, solidarity groups, and new forms of social cooperation; networks that can in the future become formal or informal structures of civil society and increase the capacity for resistance, demand, and collective organizing. Confronting restrictions and repression has also taught society new ways of participating and educating each other; scattered and cautious actions, small gatherings, and private conversations form the initial nuclei of future civil institutions. Rather than being obstacles, restrictions have become a stimulus for innovation, resilience, and the strengthening of social capital.

Ultimately, the long-term consequences of this experience can be seen in four simultaneous axes: the production of a new logic of struggle, the redefinition of the relationship between society and power, the formation of new political sensitivities and imagination, and the strengthening of civil society and the capacity for collective organization. The interaction of these four axes shows that even the apparent failure of protests creates an active and wounded memory that persists across social time and shapes new modes of action, resistance, and political imagination. State violence and repression, in this perspective, are not only limiting but also productive of new paths for social and civic re-creation, opening up new horizons for collective action in the years to come.

delayed

What happened in January 1404 was a moment when organized violence and state repression not only limited street action, but also profoundly and long-term transformed the structure of society’s collective memory and political imagination. This experience showed that even in conditions of threat, obstruction, and restriction, collective action and the capacity for political imagination in society are not extinguished, but are reproduced in scattered, cautious, and underground forms. The wounded and scattered memory of this event not only records the past, but also creates a space for the re-creation of future politics, action, and imagination.

The long-term consequence of this experience can be seen at four levels simultaneously: first, the production of a new logic of struggle that makes possible the flexibility and underground networks of collective action in the years to come; second, the redefinition of the relationship of society to power and institutions that reminds us that political action is always measured in relation to limits and risks; and third, the production of new political sensitivities and imaginations that allow for the emergence of innovative and unconventional strategies to confront the blockage; and fourth, the strengthening of civil society and the capacity for collective organizing. These four axes, interacting with each other, show that even the apparent failure of protests can be an engine of social and political regeneration in the future.

In other words, state violence and repression, while creating constraints, also provide space for innovation and collective resourcefulness. The experience of January, by recording moments of repression and the conquest of digital spaces, offers a futurological model: a society that learns to redefine its action in threatening conditions, keeps its memory active, and maintains the possibility of new political imagination. This trend shows that collective experience, even in the face of total repression, can be the engine of the formation of new modes of resistance and social restructuring, opening up new horizons for collective action and long-term politics.

The experience of January reminds us that collective memory and flexible political action are not merely tools that represent the past; they are forces that shape the future. Violence and constraint, while attempting to contain society, simultaneously provide the ground for the formation of new strategies, networks, and political imagination. The long-term consequence of this experience is therefore not only visible in immediate changes, but in the redefinition of politics, memory, and collective action for the years to come; a horizon that shows how society can reproduce and innovate in conditions of repression, and create new paths for resistance and collective imagination.

Footnotes:

Merrill, S. (2024). Remembering like a state: Surveillance databases, digital activist traces and the repressive potential of mediated prospective memory. Memory Studies, 17 (5), 1177–1194.

Rigney, A., & Smits, T. (Eds.). (2023). The visual memory of protest . Amsterdam University Press.

Sebastian, B. (2024). Memory and social movements in modern and contemporary history: Remembering past struggles and resourcing protest. Social Movement Studies , 1-2.

Tags

Collective memory Crime against humanity Criminal Historical memory Massacre 1404 Mina Youth peace line Peace Line 178 Repressive institutions Suppression The Di 1404 Uprising Uprising of 1404 ماهنامه خط صلح