Violent subjugation: Why do the repressive forces shoot? / Hermine Hordad

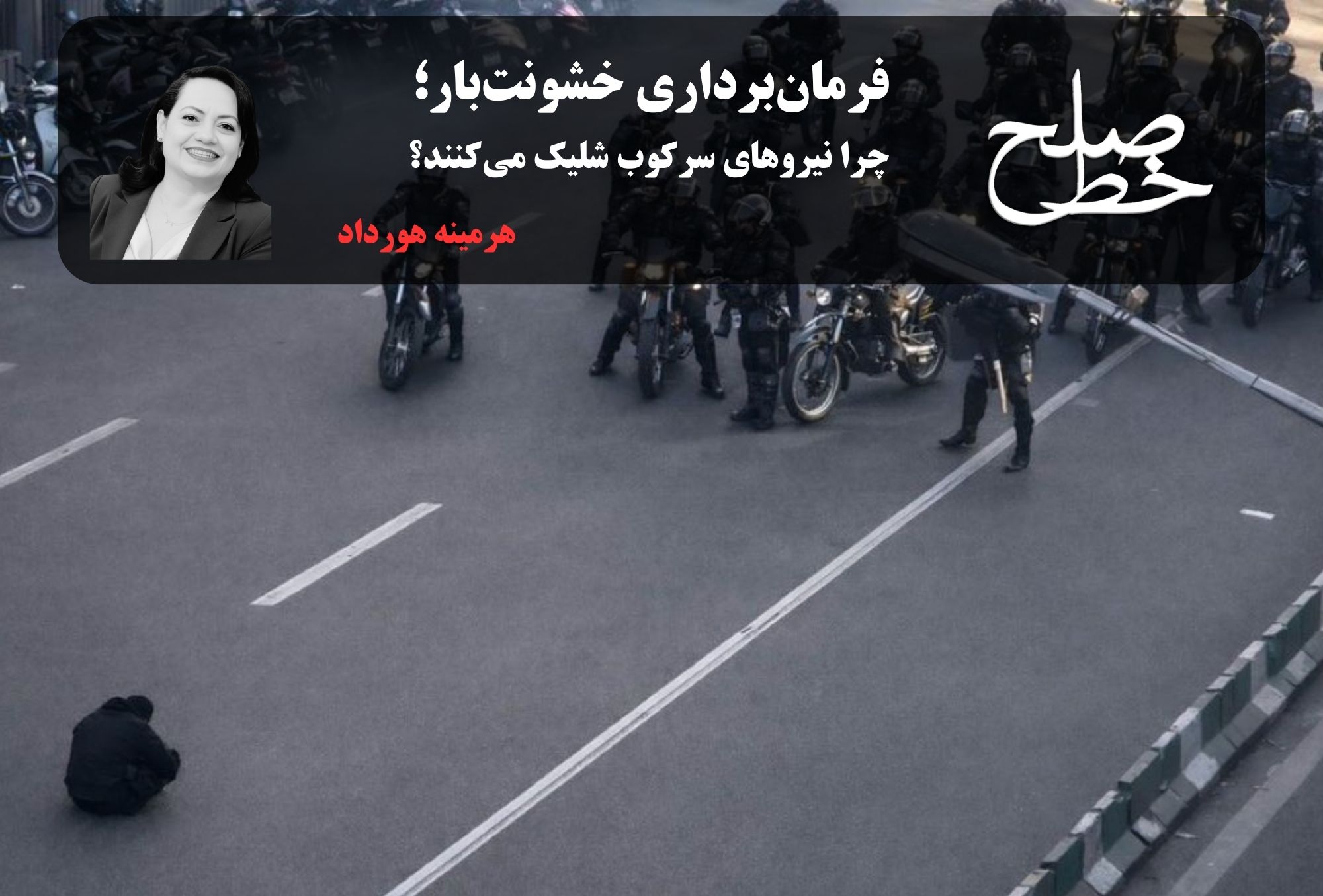

A young man, caught in the crosshairs of a slave, sits cross-legged on the asphalt in the most defenseless human situation; in front of him stands the Islamic Republic’s suppression machine. A few meters away, a girl and a boy are shielding their chests from forces holding weapons. The statistics are horrifying. It is difficult to read the news, and believing the facts of the killing and violence seems heavy and unimaginable to many non-Iranians. Incomplete statistics, even trickle-down statistics from the very first days after January 18 and 19, show that this time, in January 1404, one of the bloodiest massacres in Iran’s contemporary history was carried out by the Islamic Republic.

These crimes were committed by people who live among people and are no different from others on the surface. Some have committed crimes to preserve the system of which they are a part, and some have considered themselves “instructors and excuses.” The issue is not simply the evil and criminality of a government; it is the mechanisms that make obeying the order to kill possible and even normal for a part of society, to the point where an individual can stand in front of their fellow human beings and countrymen and shoot and even get away with it. The fundamental question is how can a human being act so violently? How can they, regardless of any human perspective, raise a weapon and kill their fellow countrymen, contemporaries and peers – who have come to the streets empty-handed and for their most humane demands? The forces of repression themselves are from this same young generation and live in this same society. The question is, how do these same people, in the moment of protest, abandon their human empathy and become a submissive force of repression; how do they shoot their own generation and kind, and sometimes get away with it? In the first episode of the film “The Devil Does Not Exist,” Muhammad Rasoulof portrays one of these people in his daily life; an ordinary person with an ordinary life. However, the question remains: how can people, time and again, remain obedient to the command of fire against the most legitimate and humane protests for the rights of a part of their society?

Other questions arise: Who are these people? Where and how are they trained? And what do they do in everyday life, when there is no direct repression?

Iranian society has had a long experience of fighting dictatorship in its contemporary history. During the Islamic Republic, these struggles have become more continuous, complex, and layered. In many analyses, based on studies of other revolutions, it was said that if a certain percentage of the population took to the streets, the government and its forces would not be able to resist, or if soldiers were given flowers and chanted slogans of support, the moral reaction would force them to lay down their arms. But in the Islamic Republic, the forces of repression are neither classic soldiers nor military forces trained to protect society with military ethics. They are either special units trained for urban warfare and the suppression of citizens, or plainclothes forces that cannot even be identified from normal routes.

From the perspective of political sociology, it is a mistake to view the forces of repression simply. Just as the Islamic Republic has layered its power structures, it has also organized its forces of repression in a layered and intertwined manner. Such a structure ensures that even if some of the forces become morally hesitant or collapse, other layers can continue the repression and repair the hesitant parts.

These layers are formed from different groups and classes of society; from the downtrodden and marginalized to people who do not even have a registered identity. The issue is not their lineage or place of birth; the issue is that the government deliberately and for various reasons has placed a group in a state of identitylessness and then recruited them with the promise of identification documents or minimal livelihood opportunities for themselves and their families. Other layers are made up of sections of the middle class; not necessarily out of ideological belief, but through privilege, rent, job security, and a sense of proximity to power. All of these organizations have been formed in a context of an institutionalized culture of authoritarianism and patriarchy that has been reproduced in the mechanisms of the Islamic Republic for years.

In this structure, the dehumanization of protesters takes on a central role. From the official language and media to schools, universities, Basij bases, and religious bodies, the government constantly teaches othering and enemy-making. This process goes so far that the protestor is no longer considered a citizen, but is defined as a “threat.” In such a framework, the oppressor can obey the order to shoot and accept violence with the justification that if he does not shoot, he will himself become a victim of the enemy; an enemy that has been created in his mind for years and is today called “the enemy.” Protesting suffocation and high prices, with this linguistic shift, is transformed into “riots,” and the order to shoot is made to appear legitimate. This logic has been reproduced in the heart of successive uprisings, each time with a shorter interval than before. As repression has spread, the government has continued to distribute corruption, grant privileges, and create weak and dependent oligarchies; groups held hostage by privilege and fear within the system. Here, the simple and deadly discourse of the government becomes tangible: “If you don’t hit, you will be hit; if you don’t kill, you will be killed.” The issue is not just the behavior of the repressive force; it is the issue of an order that rationalizes violence, makes obedience a virtue, and defines man as an enemy before he knows it.

What is happening in Iran today is not a unique phenomenon, from the perspective of political sociology and the history of systematic violence. This pattern has been repeated in other authoritarian regimes. The concept of the enemy is taught from childhood, the habituation of minds to dehumanization, the recruitment of forces from the margins of society, the multilayered structures of repression and the use of fear to ensure obedience. In all of these examples, the violence was institutionalized in minds and languages before it reached the streets.

The examples of Nazi Germany, Rwanda, Chile, Argentina, the Soviet Union, and Syria show that institutionalized violence ends either in violent collapse, in bitter compromise, or in silence that transfers violence into the future. In all of these paths, the human cost has been enormous. The forces of repression have sometimes been instruments of the system, sometimes its victims, and often both roles at the same time. Some have been tried, some have been forgotten, and many have continued to live with the burden of memory, denial, and fear. History shows that institutionalized violence, while costly, is not sustainable. Sooner or later, it either topples the government or erodes society from within. Violence becomes dangerous and enduring when it becomes normal, everyday, and institutional; when shooting a fellow citizen no longer requires personal hatred and when killing is seen as simply “doing the job. ” In such a situation, obedience replaces moral judgment, individual responsibility is shifted upwards, and the human “victim” is no longer seen as a target or threat.

What happened in Iran in January 1404 can be understood precisely within this framework. The Islamic Republic has used and reproduced violence as part of its governance, not at specific points, but from the very beginning of its establishment; from the repression and executions from the early hours of its establishment, from the repression of the first months in Kurdistan and throughout Iran in the early sixties and the widespread executions of the summer of 1988, to the university dormitories, the street protests of the following decades and the recent uprisings. Iranian society is not faced with sporadic events, but with a continuous process of institutionalized violence.

If this cycle is to be stopped one day, its starting point is not in bullets and the streets, but in language, public education, and the return of a human and moral perspective to the center of politics. A society that can see humans as human again will be able to move beyond violence. The same thing we heard in the younger generation of Iran in the videos of “Sarina Esmailzadeh” and in the wills whose handwritten photos are being published on social media today. Scenes like a young man sitting on all fours in front of the forces of repression, or a girl and a boy whose last romantic kiss before joining the protest is recorded, show that Iranian society as a whole still keeps morality and humanity alive; although the path of transition from violence will be risky and tortuous.

Tags

Crime against humanity Criminal Dictatorship Hermine Hordad Kahrizak Massacre 1404 peace line Peace Line 178 Repressive institutions Special unit Suppression The Di 1404 Uprising Uprising of 1404 ماهنامه خط صلح