Fashion and the Representation of Distinction: From Personal Taste to Class System/ Naeimeh Doostdar

What is seen on the streets today is not merely a variety of styles, but a silent, ongoing competition between social classes—inscribed on the surface of the body. Hair color, eyebrow shape, the cut of a manteau, and even the quality of makeup have become markers that reveal opportunities, limitations, and economic divides. In a society where class mobility has become increasingly difficult, appearance has more than ever become a language of power. Contrary to popular belief, a person’s appearance is not solely an individual or aesthetic matter, but lies at the heart of power relations, economic inequality, cultural capital, and social mechanisms. From Thorstein Veblen, the American economist and social theorist, to Pierre Bourdieu, the prominent French sociologist, it has been shown that appearance functions as a language—one through which individuals not only define themselves but also signal their social position. In Iran, this language has taken on new and intense meanings, especially under economic pressure, state restrictions, and generational change.

Theoretical Roots of Distinction: From Conspicuous Consumption to Cultural Capital

Through his concept of conspicuous consumption, Veblen argued that many of our stylistic choices are part of a social game—a game where increased or exclusive consumption conveys social prestige. Bourdieu transformed this idea by showing that what we call “taste” is in fact shaped by family upbringing, class structure, and cultural experience. From his perspective, hair color, makeup styles, clothing choices, and even posture carry cultural capital. Society recognizes these signs, and social classes, whether intentionally or not, use them to demarcate boundaries. In Iran, these same mechanisms operate—but with added complexity, as they are entangled not only with economy and culture but also with politics and state control. In Iran, class distinction manifests not only through consumption and style but also through the possibility of consumption and freedom of choice.

The Beauty Economy and Inequality: Appearance as Class Evidence

A person’s appearance is, above all, contingent on financial means. Economic disparity in Iran has widened, and this gap is vividly visible in appearance. The cost of beauty services—from hair coloring, professional blowouts, and nail care to hair treatments, Botox, dermal fillers, and laser procedures—in major Iranian cities often equals several days to a full month of a working-class income. Thus, access to these services has become a class symbol. On the other hand, quality clothing in Iran—due to sanctions, a weak domestic textile industry, inflation, and smuggling—comes at a high price. Purchasing a well-made manteau, European denim, or genuine leather shoes is beyond the reach of much of the population. As a result, the quality of items and the way they are coordinated has become a visible indicator of economic access. In today’s Tehran, “fitness,” “on-trend hairstyles,” “subtle yet professional makeup,” and “simple but expensive clothing” all reflect financial and temporal resources. Conversely, disadvantaged classes are often forced to rely on cheaper market clothing, low-cost beauty services, and longer-lasting styles. The contrast in quality and style acquires class significance—one that is often deeply unfair.

Aesthetics and Judgment: How Styles Produce Class

In Iranian society—as in many others—aesthetic styles carry cultural judgments. Subtle makeup, cool-toned hair colors, short manteaus with clean lines, tailored suits, and minimalist handbags are typically perceived as tasteful and “modern” among the affluent middle class. In contrast, heavy makeup, low-quality fantasy hair colors, flashy manteaus, or embellished bags are often associated with “popular” or lowbrow aesthetics. These judgments are culturally rooted but actively reproduce class divisions. Styles more accessible to lower-income groups are unfairly devalued. This dynamic has pushed the middle class toward luxurious minimalism—a style that appears simple but requires significant financial and cultural capital. In Iran, “luxurious simplicity” has become a class signifier, since high-quality materials, precise tailoring, professional coloring, and minimal yet coordinated makeup all come at a cost.

The Body in Iran: A Heightened Field of Distinction

In Iran, the body bears more social meaning than in many other countries. Several factors have intensified this condition:

First, government restrictions on dress and the body have turned appearance into a site of resistance. Many Iranian women, despite state-imposed mandates, have transformed their appearance into a language of cultural distinction. Specific hairstyles under the headscarf, makeup quality, or even how a shawl is worn have all become carriers of cultural and class messages.

Second, widespread economic pressure has increased the symbolic value of beauty. In a society where upward mobility is limited, appearance often becomes a tool for social competition. A beautiful body, healthy hair, blemish-free skin, low weight, and physical fitness are interpreted as signs of self-management, self-control, and success—concepts that are in fact rooted in class-based opportunities and resources.

Third, the pressure on women is greater than on men. In Iran, women’s beauty is not only a matter of consumption and style but also one of security, social power, employment opportunity, and even access to public space. Thus, grooming and self-presentation have become a “social necessity” rather than merely an aesthetic choice for many Iranian women.

Social Media in Iran: Intensifying Inequality Through Image

Instagram, which prior to widespread censorship was the most popular visual social network in Iran, played a significant role in shaping visual distinctions. Content creators, fitness trainers, makeup artists, beauty clinics, and influencers presented a standardized image of beauty—often accessible only to the upper-middle class. Flawless skin, fit bodies, Hollywood-style makeup, cool-toned blonde hair, European fashion, and foreign brand-name handbags were part of this imagery. In contrast, lower-income groups faced psychological pressure because these beauty standards were out of reach. The result has been the emergence of a new form of class-based shame and costly attempts to mimic upper-class appearances. Practices such as paying in installments for laser treatments, buying counterfeit bags, using low-quality hair dye, or opting for heavy makeup are all attempts to participate in the “beauty field” at a lower cost. This condition is more structural than personal: social media in Iran has rendered class distinctions visual, comparable, and constantly visible.

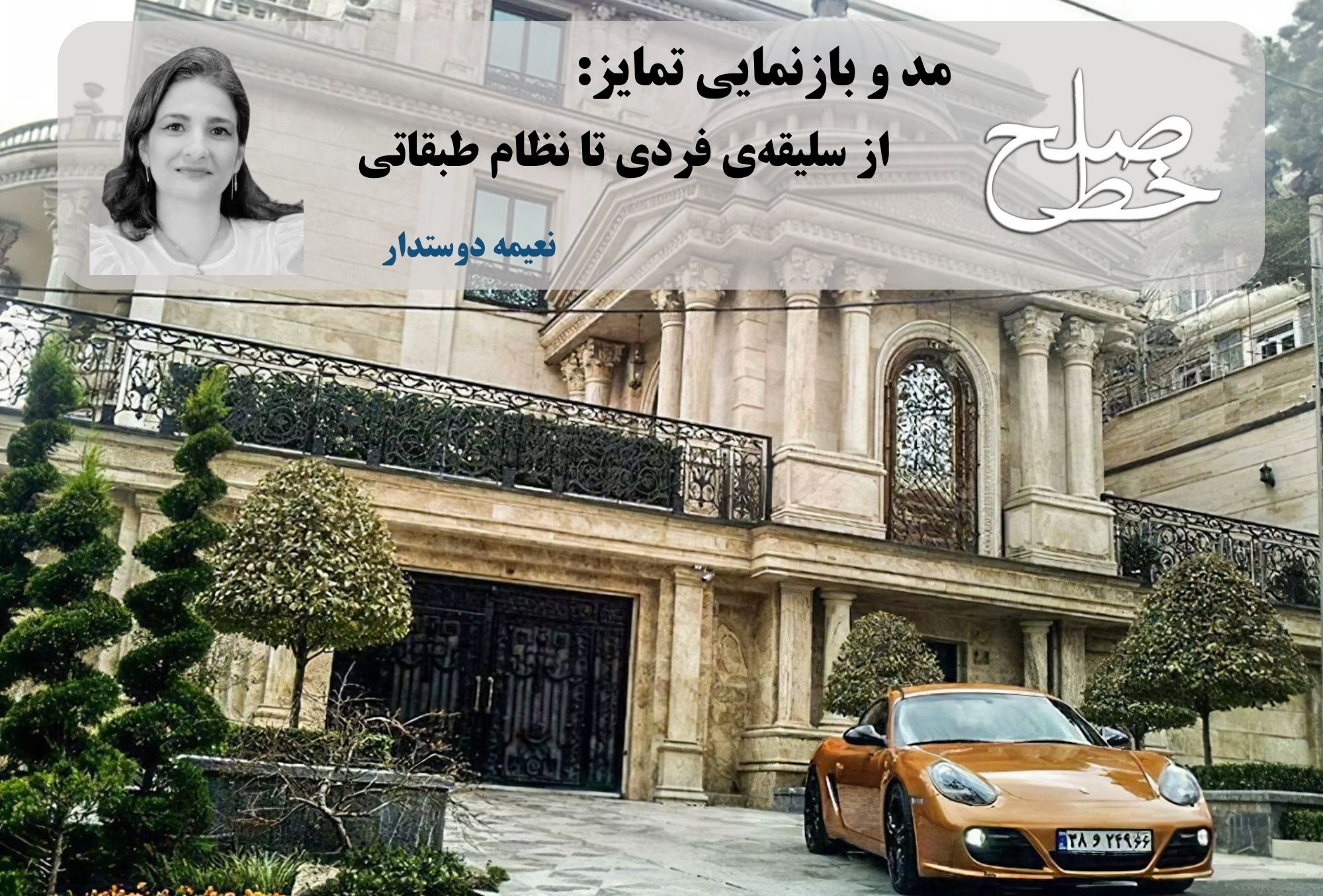

Class Distinction in Iranian Dress Styles

In Iran, dress style conveys class and identity perhaps more than in many other countries. In Tehran, simply moving from one neighborhood to another reveals stark differences in people’s appearance. In areas like Vanak, Gheytarieh, Elahieh, or Lavasan, styles are predominantly minimalist, with neutral colors and high-quality fabrics. In parts of East or South Tehran, styles are more colorful, diverse, and makeup tends to be heavier. These differences are not just a matter of taste or personal preference—they reflect varying economic means, cultural capital, and even different lived experiences of the world. The high cost of quality clothing, import bans, the weakness of the domestic fashion industry, and the inflated prices of foreign brands have made clothing disparities highly visible. Meanwhile, the affluent middle class has sought to symbolically distance itself by emulating European and Scandinavian fashion trends.

Hijab and Distinction: How Restriction Deepened the Divide

In Iran, mandatory hijab policies have not erased distinction—they’ve made it more complex. Before the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising, elements such as the headscarf, manteau, how a shawl was worn, the color and sleeve cut of garments, and the length of clothing all became tools of distinction. The affluent middle class expressed their style through short manteaus, neutral colors, light shawls, and subtly visible hairstyles. The working class, through cheaper manteaus, bold prints, or ornate scarves, were culturally labeled. Even details like “eyebrow grooming” or “nail polish color” carry class signals in Iran. This shows that state restrictions have not erased differences but have instead driven them into more subtle, symbolic, and hidden domains.

Class Reproduction in Iran: How Appearance Is Passed Down Generationally

As in many other countries, family plays a central role in shaping taste in Iran. Children who wear quality clothes from an early age, grow up in affluent neighborhoods, are exposed to global fashion styles, and have access to beauty services develop different aesthetic preferences from childhood. School, university, and the job market all intensify these differences. In Iran’s job market, a “suitable appearance” often means alignment with middle-class aesthetic norms—structurally placing individuals from lower classes at a disadvantage. This is one of the hidden pathways through which inequality is reproduced.

Appearance: A Language of Inequality and a Battleground of Class in Iran

In the end, fashion, clothing, makeup, and hairstyle in Iran are not superficial elements but mechanisms for representing and reproducing class distinction. What we call “taste” is in fact the product of power structures, economic inequality, cultural experience, and regulatory policies. Due to its particular combination of sanctions, inflation, social control, economic pressure, and generational shifts, Iran represents one of the most intense arenas of visual distinction in the region. In Iran, a person’s appearance reveals not so much who they are, but what access they have had and in which social field they have lived.

Created By: Naeimeh Doustar

Created By: Naeimeh DoustarTags

Class division Layers of sediment Lifestyle Lowland Naeimeh is a friend/lover. Paragraph peace line Social networks Social stratification Unemployment رسه School ماهنامه خط صلح