Fire in the heart of “Aghajan” / Azar Taherabad

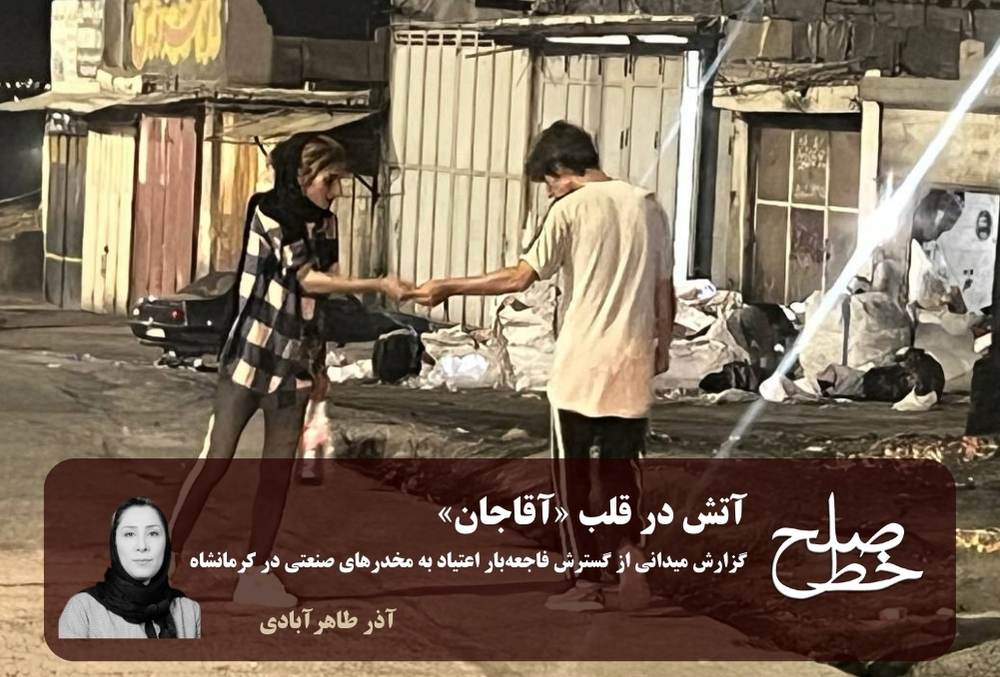

The hot summer morning air in “Aghajan” is bitter; the smell of burning smoke, city sewage left in the streets, and the strong scent of mixed substances. The approximate distance from this neighborhood to the heart of the city is about ten minutes. From the moment I step into the neighborhood, I realize that this is not a “normal” life; here, addiction is not just a peripheral problem, but a part of the daily fabric of these people’s lives.

History of Aghajan: From the working-class neighborhood to the outskirts of poverty.

The old residents of Kermanshah say that the Aghajan neighborhood in the 1940s and 1950s was one of the most lively areas of the city. Most of its inhabitants were workers and farmers from the surrounding lands. The houses were small but full of life. 70-year-old Karim, who has spent his entire life here, remembers: “Back then, people used to help each other. Even if someone was poor, their dignity was intact. But after the war and the rise of unemployment, many either migrated or fell into the trap of addiction.”

Comparison with other neighborhoods in Kermanshah.

A social activist in Kermanshah, who does not want his name to be revealed, speaks about peace: “Sir, it’s not just neighborhoods that are struggling with this crisis. Neighborhoods like Jafarabad, Hekmatabad, Anahita, Chamran, and Darreh Deraz also have similar problems. But due to the old structure, narrow alleys, and high population density, these areas are ideal for drug distribution networks.” He explains that compared to these areas, Sir has a higher rate of teenage consumers, and this issue makes the future of the neighborhood even darker.

I am still walking in the neighborhood; women with tired eyes look out from their windows, children pass by the addicts sleeping on the stairs and walls, and men who want to appear indifferent turn their uncertain gaze. I walk in the neighborhood of Mr. Aghajan to hear the stories of those who are daily struggling with this reality; the stories of families, therapists, local activists, and those who stand at the center of the crisis themselves.

“Since glass has become cheap here, everything has changed.” Reza, a man in his forties who grew up in the neighborhood, repeats his sentences with a distant look in his eyes. He sits next to a small grocery store, his hands tightly clenched and his voice tired. According to him, before the prevalence of industrial drugs, the consumption pattern in the neighborhood was mostly opium and then hashish. “But now, young people start using glass at the age of 15-16. Its effect is quick, but it destroys people. Both their bodies and minds.” He points to the semi-abandoned houses and says, “Do you see that? That’s a hangout spot. Neither the police do anything about it, nor does anyone have the courage to speak up.”

In the Sarashibi neighborhood, which ends at the Imam Khomeini Hospital – Center for Burn and Eye Trauma, a group of teenagers are gathered. I approach them and introduce myself, but a few of them quickly leave the group. One of them, who introduces himself as “Milad”, after a brief conversation, in response to a question about the peace line, says weakly, “Do you think we became addicted? At first it was just for fun and laughter, now it’s become a daily job and I’ve become a drug dealer and a bartender.” When I ask if your parents are aware of this situation, he says, “Do you think they don’t know? So where do I get the money to give them? I have no job, my father has been dead for years, my mother is a housewife and has no job, and I have to support myself and my three siblings.”

I ask the residents of the neighborhood about the sellers and producers, some are not willing to be interviewed and some speak indirectly; a strange fear is evident in their eyes that forces them to an involuntary silence.

“Saeed” is a shopkeeper in the neighborhood. When I ask him about how he distributes goods, he takes a deep breath and says, “Everyone knows. It’s clear from morning till night. Sometimes families come and buy for themselves. The authorities also know, but it seems there is a red line and no one dares to enter.” He talks about the lower prices of industrial goods compared to traditional goods and says that this factor has made consumption easier for low-income groups.

I am going to the university to meet with Dr. Ameri, a clinical psychologist. He meets with clients every day at a self-care center and asks them about their clients. He says, “Most of them are under 30 years old. Industrial substances have very aggressive effects on the nervous system. Treatment is long, complicated and expensive, and when the person returns to the same environment, the chances of relapse are very high.” He also talks about the lack of capacity in detox and psychotherapy centers, as well as the high costs of treatment. “Many families do not have the financial means or necessary social support to quit.”

In continuation of the conversation, Dr. Amiri mentions another topic that I am amazed by, a topic that may be a fresh headline for the next report: “The obscenities born from drug addiction.” Amiri refers to the prevalence of obscenities in this neighborhood and says that in addition to drug abuse, attention should also be paid to the prostitution of women, which is growing under its shadow. Alongside the houses that serve as drug dens, there are also rooms for this purpose where women who do not know how to earn a living have turned to prostitution.

As my meeting with Dr. Amiri comes to an end, I return to the same streets. Now, as I walk through the neighborhood, I can clearly identify the houses that have been turned into drug dens. These houses are usually closed off, with their windows and doors shut, but through the cracks, one can see dim lights and scattered smoke coming out.

“Hamid, a man who has worked in the neighborhood for years and is now trying to leave, says: “When someone becomes addicted, they stay right here. No one helps, and there is no support system. Everything is in front of your eyes – your home, friends, and the street. Leaving here means separating from everything.”

One of the clear tragedies in Aghajan is the involvement of children and teenagers. “Leila”, a mother of two young children, and her husband, who is still struggling with substance abuse and works as a laborer in an industrial town, says: “My son comes home from school and tells me that so-and-so slept on the stairs last night. How do we explain this to our children? Here, children witness things every day that they shouldn’t.” She continues: “This neighborhood has turned into a school for how to use drugs. You can see at least two people in every corner and every house, using drugs in front of children. How can I keep my children away from this danger? God knows, we don’t have the financial means to move to a better neighborhood and have a normal life.”

The narrative of relapse and repetitive return is also one of the main lines of crisis. “Majid”, 35 years old, who has quit twice and returned to the cycle of consumption, says: “The quitting center helps, but when you come back here, everything starts all over again. Your friends, acquaintances, even the people who used to encourage you when you were clean, now want to be together again. It’s also very difficult when your living situation doesn’t change.”

From a social perspective, the neighborhood of Aghajan is the result of a long-term process, “structural unemployment”, “reduction of social capital” and “weakness of urban services” are accelerating factors that are pulling the youth and adolescents of this neighborhood into this whirlpool much faster than one can imagine. The role of distribution networks in the spread of the crisis is also undeniable. “Arash”, a former consumer who is now trying to help others, says: “There is one main distributor, and then a few under him. Young and underage adolescents are employed for delivery because their identification and punishment is not easy.” He emphasizes that many of those who distribute have a history of consumption themselves and have entered these networks to cover their consumption or living expenses.

The response from official institutions is a mixture of action and promises. In a conversation with the local police chief, Bahman stated that “clean-up plans” have been implemented and several people have been arrested. In the Dieselabad prison in Kermanshah, the drug ward has always been one of the busiest wards, but accurate statistics have never been published and several death sentences are carried out there every month. However, local activists and families say that temporary arrests and long prison sentences without social and medical follow-up have had no real impact. When detainees or prisoners are released, they return to the same neighborhood and the cycle continues. What the police can do is just arrest, but without effective empowerment, treatment, and employment programs, it will not have a long-term impact.

Experts suggest that in order to overcome this crisis, at least three simultaneous strategies should be implemented:

1- Urban development and elimination or transformation of hangout spots.

2- Creating local and sustainable job opportunities for youth; and.

3- Strengthening prevention and treatment programs at the neighborhood level, including the presence of counselors in schools and local centers.

“Graound”, a sociologist and researcher on social issues in Kermanshah, believes that a purely security-oriented approach to the issue of drugs, although it may lead to short-term increases in seizures and arrests, is not a sustainable solution in the long run. He refers to the peace line: “Many of the individuals who are arrested as small-scale dealers or carriers of drugs are themselves victims of economic conditions, unemployment, and chronic poverty. When the youth unemployment rate reaches over 30% in some border towns, the allure of entering into smuggling networks or drug use becomes even greater for some of them.” Graound also mentions the issue of social stigma: “When someone is arrested on drug charges, even after their release, they do not have the opportunity to reintegrate into society and find a dignified job. This cycle leads to the reproduction of crime and dependence on smuggling networks.” According to him, in rural and marginalized areas of Kermanshah, the lack of

During the few days that I was in Aghajan, I saw several families who have surrendered to the situation, and a few others who still have hope.

Elham, a volunteer social worker, brings food and clothing to this neighborhood every week. She says, “Sometimes someone agrees to come to the rehab center. But when they come back and everything is the same, the return is inevitable. We need plans that can give them a new life, but the budget of community organizations is very limited and the number of these households is not only high in this neighborhood, but also in several other neighborhoods.”

Most of the people who live in this neighborhood have families who are struggling with addiction issues. Most of them work as garbage collectors. At the end of this neighborhood, where it ends in the freeway, there are centers that operate at night and may be closed during the day, but are twice as active at night. If you visit this neighborhood at night, you will see people who look like Hollywood movie zombies, carrying bags of garbage from the neighborhood towards these centers to exchange for money to buy drugs.

The role of media and news silence.

Many residents believe that local media, such as radio and television, do not pay enough attention to the crisis of our country. “Saeed”, a shopkeeper in the neighborhood, says: “We who live here see the news every day. But in the news, it’s as if we don’t even exist.” Experts say that media coverage can draw public and government attention and create social pressure for action. However, some media outlets, due to concerns about consequences, are less likely to report on such issues.

In summary, it can be said that, sir, these are condensed examples of something that if not taken seriously, can lead to even greater crises: deprived youth of education and employment, families whose abilities have been analyzed, and children and adolescents who are exposed to destructive behaviors. The solutions are not simple, but they are clear: a combination of social and urban policies, strengthening treatment and rehabilitation, and prevention programs at the school and family level must be implemented quickly.

When I leave the neighborhood, the last image of me is a man sitting on the stairs, his trembling hands on his knees, staring at the sky; there is no hope in his gaze, nor fear of the future. The master is alive, but every day he is faced with a crisis that is deeply internal and structural, a crisis that if not controlled, will not only endanger this neighborhood, but also the next generation of this city.

In conclusion, as a field reporter, I believe we should take another look at our leaders; not just with short-term security plans, but with long-term social-economic programs that can provide the opportunity for leaving, empowerment, and return to a dignified life. Without the involvement of government institutions, civil society organizations, and the people themselves, this wound will only deepen every day.

Tags

Addiction Artificial drugs Azar Taherabad expensive Narcotics Paragraph peace line Peace Line 172 Swelling The neighborhood of Aghajan. Unemployment ماهنامه خط صلح