When women woke up – Part 1

On the day when a large group of women gathered in front of Naser al-Din Shah’s carriage and advised him to improve the affairs, a new era had begun and the era of Iranian women’s social presence had arrived. These were the same women who were previously only seen inside their homes and had no way of participating in society. But the story of the tobacco boycott and the subsequent rise of constitutional whispers changed the image of Iranian women and portrayed a new image of them. To the extent that many historical studies consider the beginning of the Constitutional Revolution as the “awakening” of Iranian women and see it as the starting point of a movement called the Women’s Movement.

The actions of Iranian women in donating their small savings to support the establishment of the National Bank, and the presentation of valuable jewels by wealthy women for the same purpose, and finally the organized attack of armed women on the National Consultative Assembly, almost without exception, can be seen as key scenes in the beginning of the tradition of women’s activism and display of their political awareness. It was during this period that Iranian women opened their eyes to see beyond their small prisons and also to look beyond the walls of their harem. In fact, the women’s movement in Iran cannot be studied separately from the Constitutional Revolution. The activities of women during the years of the Constitutional Revolution gave rise to a new sense of nationalism and a strong enthusiasm for the realization of individual and social rights, and was a turning point in the history of Iranian women. For this reason, women’s education held a special place in the eyes of pioneering women, although the discourse of women’s education in Iran was never influenced by or derived

In such conditions, with the beginning of the Constitutional Movement, women who were previously faced with restrictions even for leaving their homes, joined the streets and joined the ranks of the advocates of the Constitution with the opening of the country’s political and social space.

Women had, of course, previously experienced successful movements such as the Tobacco Protest and Bread Riots in 1898, but with the start of more serious and prominent conditional movements, they stepped onto the field with greater determination and vigor. They participated alongside men in bringing scholars to mosques for speeches and protection, as well as joining in the front lines of battle.

During the eleven-month siege of Tabriz, women of this city took on many tasks behind the front lines. They cooked food for the fighters, sewed clothes, knitted socks, filled empty gun cartridges, and delivered news and food from one trench to another. They also distributed night letters, took care of the wounded, and sold their dowries and jewelry to financially support the fighters. Some even fought in battle dressed as men and were killed.

After the conditional victory, women continued to support the conditional movement. When it was decided to raise capital for the National Bank, many women sold their jewelry and household items to raise a considerable amount to help the National Bank. There are many stories of women who donated all their savings and lifelong reserves, sometimes a gold necklace and sometimes 5000 tomans, to the National Bank. In the face of sanctions on imported goods and the promotion of domestic textiles, women played a significant role and tried to encourage women to support domestic products by forming associations and writing articles in newspapers.

Women are leading the strike.

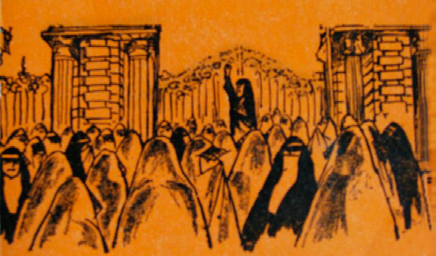

The most significant impact of women during that time, however, may have been seen in the Russian ultimatum and the passivity of the government-men of that era. Russia, as a result of Shuster’s reforms, demanded his expulsion from the Iranian parliament and gave an ultimatum to the National Consultative Assembly that if they did not accept Shuster’s expulsion, they would attack Iran. The Assembly was on the verge of accepting Russia’s ultimatum. After this incident became public, active Iranian women in the cities of Isfahan, Qazvin, and Tabriz moved towards Tehran and succeeded in organizing a 500-person strike with their mobilization.

“The National Drug Association” was one of the organizers of these protests, which in addition to actively participating in demonstrations, called on Iranian women to resist and stand up against ultimatums by issuing a public statement. As Morgan Shuster recounts, “Three hundred women left their homes and harem, in orderly rows, with unwavering determination, wearing black chadors and white mesh veils, and headed towards the parliament. Many of them had hidden knives and daggers under their clothes or sleeves, and a few gave fiery speeches, saying that if the parliament lawyers hesitate in fulfilling their duties and protecting the honor of the Iranian nation, we will kill our husbands and children and leave their bodies right here.”

With such actions, women gradually came out of their homes and engaged in activities to advance the goals of the Constitution. Although these actions were not aimed at promoting the rights of Iranian women and were more in line with nationalistic goals and sentiments of that time, they were a beginning for women to enter the social sphere, which led to activities such as establishing girls’ schools, launching women’s publications, and forming women’s associations.

Women’s Demands.

During that time, women did not have a clear understanding of their independent desires and believed that the establishment of a national and constitutional government would bring freedom and the realization of rights for all people, both men and women. However, with the adoption of the constitutional law and the placement of women in the category of insane and children, and their deprivation of the right to vote, the constitutionalist women who were involved in this movement began to strive for their own demands. They formed the first seeds of the women’s movement in Iran. This movement began with national and justice-oriented goals and was supported by the establishment of girls’ schools and women’s associations.

Despite this discrimination during this period, although the number of women seeking renewal was small, they were trying in various ways to express their political and social views by using political freedom and just and equal demands for constitutional rights. They discussed the personal and social status of Iranian women, presented a different definition of “womanhood” and their duties and roles in the family and society. They identified cultural and social barriers to women’s presence in society and took steps towards achieving their rights.

Women’s activities encompassed two main areas: on one hand, they expressed their specific demands for Iranian women’s living conditions and strived to achieve them. On the other hand, they stood alongside the constitutionalist men in confronting traditionalists and authoritarianists, and actively supported and defended the National Consultative Assembly and the achievements of the Constitutional Revolution.

Some were trying to remove the obstacles in the way of women’s political activities. They asked the National Assembly to recognize gender equality and provide necessary conditions for women’s participation in the country’s political and social scene. A group of women, by evaluating the country’s political and social conditions, pursued more limited goals that they believed were achievable, such as establishing girls’ schools and promoting girls’ education. Both groups also called for a reevaluation of the patriarchal culture dominating society.

Establishment of girls’ schools, the first initiative of women.

The goal of women was to eliminate the long-standing historical discrimination in their social lives, and in order to achieve this, they needed to empower themselves. From the perspective of women in the Constitutional Era, educating Iranian girls was necessary because spreading literacy and acquiring necessary skills for social participation and presence in society and earning income would lead to women’s independence and free them from dependence on men.

So it’s not surprising that we see women establishing associations, publishing magazines, raising money, and most importantly, four years after the Constitutional Revolution, despite the incompatibilities of traditional society at that time and the opposition of opponents, in just one year and only in Tehran, they built more than 60 girls’ schools and made great efforts to educate women.