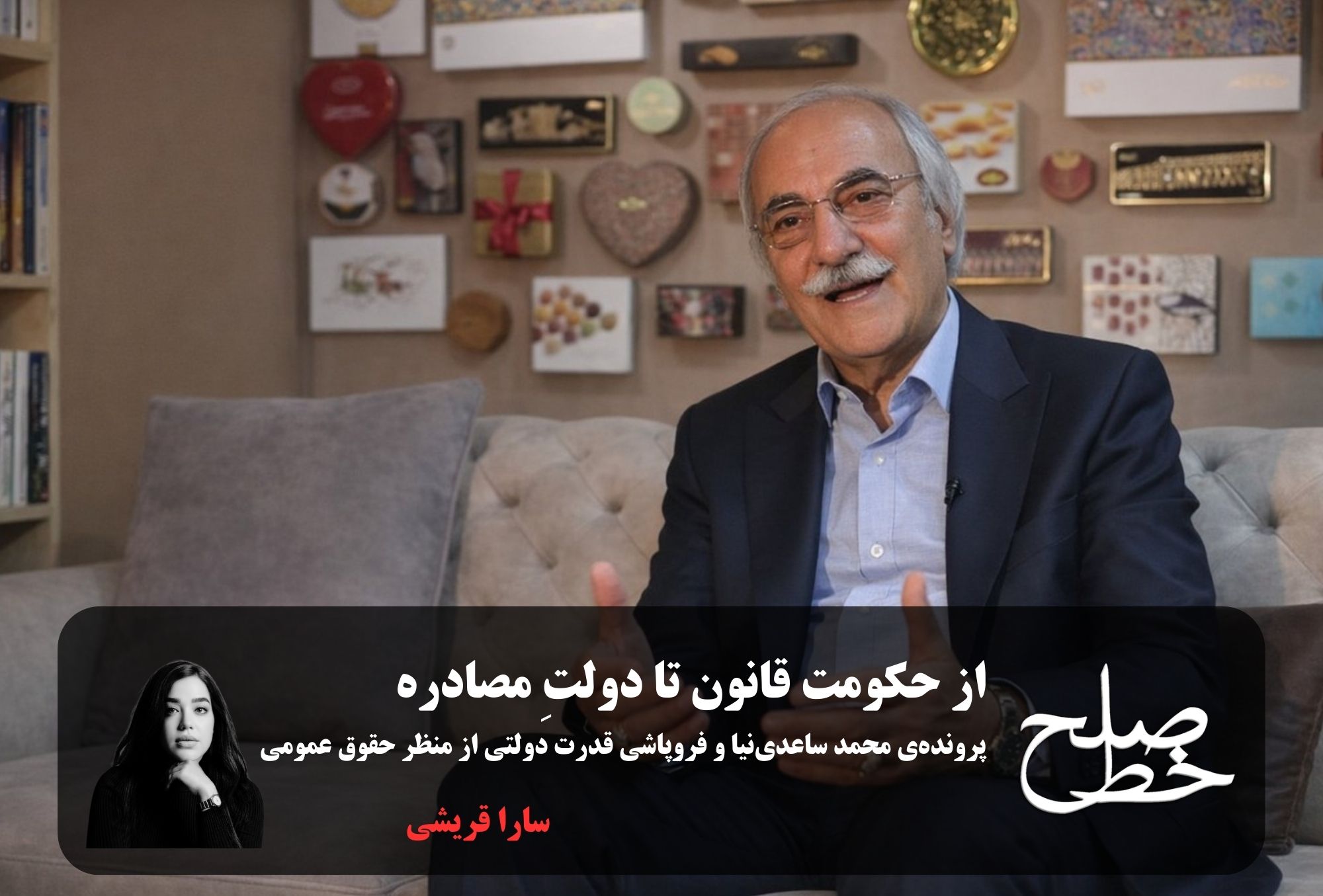

From the rule of law to the state of confiscation/ Sara Qureshi

Introduction: Terminological explanation

In this article, the concept of the general power of the state is consciously used, not political sovereignty. This choice of language is not accidental. The state here is not simply the construction of political power, but an institution that, in the logic of public law, is responsible for implementing the law, guaranteeing the rights of citizens, and creating legal security.

This article focuses on examining the collapse of the public power of the state and its implications for the rule of law.

Case Study: The Case of Mohammad Saedinia

The case of Mohammad Saedinia, an elderly and well-known entrepreneur in Qom, is a clear example of this distortion in the exercise of public power. Following his public support for protests and strikes, he and his son were arrested, their assets were seized and sealed, and their businesses were closed, leading to the unemployment of a significant number of employees.

The declared basis for these measures has been the general attribution of association with “riots and rioters,” a title lacking a precise legal definition that has led to widespread confiscation of property without a clear indictment and without the possibility of an effective defense. The Revolutionary Court has replaced criminal proceedings with confiscation, presumably citing Article 11 of the regulations, but without establishing a hostile relationship or proving the illegitimate origin of the wealth.

This shift from proving guilt to political labeling is a sign of the conscious suspension of the law and the imposition of a form of collective punishment whose effects extend beyond the accused person, including family and employees, and sends a clear message to the entire society about the transfer of power from the legal rule to coercive will, and from the security of property to the possibility of its deprivation.

Definition of confiscation of property based on Article 49 of the Constitution and Article 11 of the Regulations

In the legal system of the Islamic Republic of Iran, confiscation of property in its official sense has an exceptional and limited meaning and can only be applied within specific legal frameworks.

According to Article 49 of the Constitution, confiscation applies to property whose origin is determined to be illegitimate, including wealth derived from usury, usurpation, abuse of power, tyranny, oppression, gambling, and similar cases. In this framework, confiscation is not envisaged as an independent criminal punishment, but rather for the purpose of returning illegitimate property to its rightful owner or treasury, and its realization is subject to investigation, investigation, and issuance of a ruling by a competent judicial authority.

The judicial process can only be realized through investigation, investigation, and Sharia proof, and through the special judicial mechanisms of the Law on the Implementation of Article 49 and related regulations, including the establishment of special branches, the necessity of determining the illicit origin of the property, and the possibility of appealing against the rulings. This framework shows that the invasion of property is exceptional and requires reason and proceedings. Confiscations that are carried out without determining the illicit origin, without establishing the elements of the crime, and without following the prescribed procedures are not only contrary to international standards, but also mean the practical suspension of the very laws that the government itself relies on.

In such a situation, confiscation is neither the result of a valid criminal sentence nor the disciplined implementation of Article 49, but rather replaces the entire criminal, legal, and fair trial process. Instead of proving the crime and the illicit origin of the property within the framework of a fair trial, the state uses coercive and punitive action itself, disguised as a legal form, as a means of exercising power.

In addition to Article 49, Article 11 of the Rules of Procedure for Handling Cases Subject to Article 49 is also considered one of the principles relied on in judicial procedure. This article stipulates that the property of individuals who have left the country and whose relationship with warring groups is proven, is removed from the amnesty and confiscated by court order. In this framework, the declaratory basis for confiscation of property is not the illegitimate origin of wealth, but rather the claim of leaving the amnesty through association with certain groups.

Accordingly, in the existing legal system, confiscation of property is justified either on the basis of establishing the illegitimacy of the origin of the property, or on the basis of a claim of departure from the protection in accordance with Article 11 of the Regulations. Each of these two bases provides a different definition and legal logic for confiscation and, consequently, has distinct legal effects and consequences.

Historical background of confiscation and reproduction of the pattern

To understand the current state of confiscation as a governance model, it must be seen in the historical context of contemporary Iran.

This logic of confiscation is not new and has its roots in the widespread confiscations after the 1979 revolution, where ideological and general concepts replaced fair trial. Many of the country’s capitalists and entrepreneurs lost ownership of their assets under the rulings of the revolutionary courts, under titles such as being dependent on the court, being a tyrant, or under the title of being ineligible for property.

What is observed today is the reproduction of the same pattern with a new literature. This historical continuity shows that we are not faced with exceptional and temporary decisions, but rather with a recurring pattern at times of crisis of authority.

Formal and substantive objections to the citation of Article 11 of the Code of Criminal Procedure

Invoking Article 11 of the Rules of Procedure for Handling Cases Subject to Article 49, when used as a basis for confiscating property in criminal and security cases, faces fundamental and multi-layered flaws that make it unreliable from the perspective of criminal law and fair trial.

First, the objection is raised in the legal element of the crime. Article 11 is a regulation, not a law passed by the parliament, and in terms of the normative hierarchy it cannot be the source of creating a criminal title or punishment. Using a regulatory provision as the basis for confiscation effectively distorts the principle of the legality of the crime and punishment.

Second, the inherent ambiguity of the concepts used in Article 11 fundamentally complicates the possibility of criminal adaptation. Concepts such as relationship with warring groups or leaving the country, without precise definition, verifiable criteria, and an independent authority for determination, are incapable of becoming a legal element of a crime and are left to a broad and security-based interpretation; something that is in clear conflict with the principle of narrow interpretation of criminal laws.

Third, Article 11 has replaced the criminal trial process. In the current procedure, instead of first making a specific charge, proving the three elements of the crime, and then deciding on the punishment, the sole basis for seizure and confiscation is the invocation of Article 11. In this way, confiscation is considered not the outcome of the trial, but its starting point, a situation that reverses the logic of the criminal law.

Fourth, the principle of individual criminal responsibility is violated. Article 11 is applied in practice in such a way that its effects go beyond the accused person and also affect the family, heirs and employees, and its main message is to convey intimidation to society. Such an expansion of criminal consequences, without proof of individual responsibility, is incompatible with the fundamental principles of criminal law and the prohibition of collective punishment.

Fifth, there is a confusion of the administrative-security sphere with the criminal sphere. Article 11, which is at best a regulatory instrument for specific handling of property, in practice plays the role of a full-fledged criminal instrument, without accepting the formal and substantive requirements of criminal law. This confusion severely undermines the possibility of effective judicial supervision and guarantees of the rights of the defense. Consequently, invoking Article 11 of the Code for the confiscation of property in criminal or security cases is not the implementation of the law, but the substitution of an ambiguous regulatory provision for the full process of criminal proceedings; a substitution that leads to the practical suspension of the fundamental principles of criminal law and fair trial.

Fundamentals of Public Law: The Public Power of the State and Its Collapse

In public law, the state is not just an institution for exercising force or political control.

The government has public power when its duty is to enforce the law, protect people’s rights, and create legal security. The legitimacy of this power comes from adherence to the law and accountability, not merely the ability to use force and punishment.

Public power functions properly when decisions are made based on clear rules, predictable processes, and the possibility of oversight. If the law is set aside or only selectively enforced, the government still has power, but it no longer has public power in the legal sense.

The collapse of the general power of the state does not mean that the state has become weak or has lost its means of repression. On the contrary, the state may continue to arrest, confiscate, and punish. What is destroyed is the link between power and law; the collapse of the balance and structure of power that law has given weight to.

In this situation, the law is no longer a measure of restraint, but a tool to be invoked when necessary and discarded when it becomes an obstacle. The result is legal insecurity and a loss of public confidence that individuals’ rights and property are protected by stable rules.

Confiscation of property in such circumstances is not just an economic or judicial measure; it is a clear sign that the state has retreated from its role as the protector and guarantor of the rights of individuals and society, and its public power has eroded to the point of collapse.

Summary: A case alert

The case of Mohammad Saedinia is not an exception, but a warning sign of the consolidation of a dangerous pattern; a pattern in which regulations replace law, political labels replace fair trial, and confiscation becomes a tool for exercising authority. In such a pattern, confiscation of property is no longer an exceptional legal measure, but part of the mechanism of legal and economic insecurity in society.

The continuation of such a pattern is not limited to the weakening of individual rights or the violation of due process principles, but also directly erodes the foundations of economic and social trust. In an environment where property, legal security, and the predictability of government decisions are subject to political labeling and vague regulations, economic activity, investment, and even employment become risky and insecure areas. In this sense, property confiscation is not only a tool of political repression, but also a mechanism for producing structural uncertainty and social deterrence.

In this situation, the cost of social action or protest is not limited to the individual but spreads to family, employees, and dependent livelihood networks; which turns confiscation into a form of hidden collective punishment and serves as a warning to society as a whole.

What is collapsing is the power of the state, which was defined as the guarantor of rights, property, and legal security of society. The continuation of this process will lead to the institutionalization of legal insecurity and the structural suspension of the rule of law; a situation whose consequences will go beyond a single case or a political moment, and ignoring it will bring heavier costs to society.

Footnotes:

1- Article 49 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the laws and regulations governing its implementation (including: “Law on the Implementation of Article 49 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran”, approved in 1984, and related guidelines and regulations)

2- Historical reports and analyses on the confiscation of property after the 1979 revolution, including an examination of the procedure of the revolutionary courts and the confiscation of property under titles such as “property of the tyrant” and “non-possession of property.”

3- Reports and news related to the Mohammad Saedinia case, including announcements from the judiciary and the media about the seizure of assets, the assigned titles, and its economic and social consequences.

4- Sources of international human rights law and international humanitarian law regarding the prohibition of collective punishment and the principle of individual responsibility, including: discussions related to “collective punishment” in humanitarian law and the interpretative procedure of the Geneva Conventions.

5- Literature on public law and criminal law regarding the rule of law, legal security, the principle of legality of crime and punishment, and the need for a fair trial in the seizure and confiscation of property (domestic analytical articles on the confiscation of property and the procedure of the Article 49 court, with references to published works as much as possible).

Tags

Confiscation of property Fair trial Market strike Massacre 1404 Mohammad Saedinia peace line Peace Line 178 Punishment and discipline Sarah Qureshi Strike Suppressing protesters Suppression The Di 1404 Uprising The right to strike To reprimand or punish. Uprising of 1404 ماهنامه خط صلح