The “Alfi” wood that is now in the hands of teachers / Ahmad Modadi

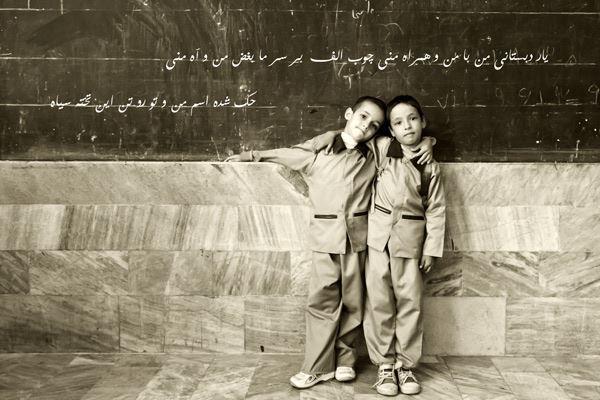

Hearing the harmony of “My Childhood Friend” in the streets of Tehran is enough to transport each of us to the passionate and enthusiastic days of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Those were the days when gatherings, mostly in university settings or with the presence of young people outside of the university, would culminate in the epic harmony of my childhood friend; the determined voices of young people singing in unison: “With me and by my side, the letter A on our heads, my grief and sigh, your name and mine, written on this blackboard…

But if you have seen the latest video of “My Schoolmate” collaboration on social media, you have surely noticed that this time it is not the enthusiastic and passionate voices of young girls and boys trying to break the sky. This time, it is the middle-aged men and women who are shouting for their schoolmate, with some even having gray hair. There is no news of those epic shouts, and with a tone that is not as exciting as before, they are reciting “My Schoolmate”. This final image is for this year’s global teacher’s gathering, which was held simultaneously in 20 provinces and more than 70 cities across the country with the call of the Coordination Council of Cultural and Educational Associations.

a.

This symbolic comparison between gatherings of previous years and recent years accurately depicts the geography and characteristics of civil activities and civic gatherings. Of course, to complete this symbolic image, we must add a few more frames. A frame of a single teacher’s gathering in Mahabad in front of the Ministry of Education, a frame of a two-person gathering of teachers in Azadshahr, Golestan, a frame of Mohsen Omrani, a teacher from Bushehr, who used his leave from prison to attend a gathering, and finally a frame of the commemoration ceremony of World Teachers’ Day in Evin Prison, with speeches from two teacher activists: Mahmoud Beheshti and Esmaeil Abdi.

***

In recent years, professional activists and civil society organizations of teachers have been and continue to be the most active part of Iranian civil society. It can be said that they are the only part of Iranian civil society that has the ability to organize and hold nationwide gatherings in today’s conditions in Iran. But how did teacher activists reach this level of collective, organizational, and networked work? How and through what process was this level of social solidarity created around the demands of teachers’ professional and civil society? And most importantly, is the way teachers operate in expanding and developing civil-professional activities and their use of their right to organize and hold peaceful gatherings capable of becoming a native model for Iranian civil society?

Answering the above questions requires examining the historical development and growth of professional-civic activities of teachers in the past fifteen years and explaining the internal mechanisms of formation and networking of teachers, which requires a separate note. This note attempts to answer the question of what characteristics the teachers’ protest movements have that are worthy of emulation by other civil society activists in Iran. The prerequisite for emulating the relatively successful experience of teachers in using their citizenship rights for organization and launching nationwide gatherings and strikes by other sectors of Iranian civil society is to understand and focus on the characteristics of teachers’ professional activities in order to develop a roadmap for replicating and expanding it in Iranian civil society.

Features of professional activities and protest movements of teachers.

Emphasis on a civil approach and professional identity.

Over the past decade, a generation of teachers has been nurtured and grown within the heart of Iranian civil society, adding to the power and richness of Iranian civil society. The new generation of teacher activists focuses on their professional identity and engages in civil and social activities, with a more civil perspective and using problem-solving methods instead of unrealistic plans. This generation has a proper understanding of the logic and dynamics of power and civil society relationships in Iranian society, and is thinking of new horizons in the educational atmosphere of Iran. This generation may be the first to consciously take steps towards depoliticizing civil and professional activities in Iran.

Individualism versus collectivism in the realm of civic activities.

The distinguishing feature and characteristic of teachers’ professional activities in recent years compared to other professional and civic activities, including students and women – as two constantly active parts of civil society – has been their distance from abstract space, intellectualism, and the prevailing universalism among civil activists, and their adoption of a completely pragmatic and results-oriented approach. Teachers define their objectives intelligently, in a limited, accessible, and measurable manner, which they can fully quantify and express in numbers.

Learning and overcoming the historical problem of “centrism” in civic activities.

Contrary to other civil and social activities, the teachers’ trade-union movement has been able to overcome the historical problem of “centralization”. Although some of the most active teachers’ unions are based in Tehran, the trade-union activists have cleverly expanded the network of trade-union activists in various parts of the country and prevented the concentration of activists and decision-makers in Tehran. The central council of the “Coordination Council of Teachers’ Trade Unions” has been managed by county-level trade unions since its establishment in the early 1980s, and the level of influence of these unions and trade-union activists in the counties has been relatively significant. As a symbolic example, four teachers who were in prison on World Teachers’ Day this year (96) were members of the Tehran Teachers’ Trade Union (Mahmoud Beheshti and Esmaeil Abdi), the Bushehr Teachers’ Trade Union (Mohsen Emrani), and the Kurdistan Teachers’ Trade Union

The inclusion of teacher training in activities has gone beyond geographical boundaries and also includes the content of the activities. The emphasis on mother tongue education in resolutions and demands of teachers, which are often demands of remote areas from the center, shows how by overcoming “extreme centralization” in setting the agenda and curriculum of civil activities, maximum support can be gained from the target community for civil and professional activities.

Continuing activity with maximum perseverance on minimum demands.

The insistence and obsession of teacher activists on intelligent distancing between professional and political activities and preventing the radicalization of protests and going beyond professional demands. Teachers and activists have reached a level of civic awareness where they pursue their civic, professional, and civic responsibilities without excitement and sloganeering, in the most practical way possible, and with commendable perseverance and steadfastness. This level of commitment and dedication to the tools and consequences of civic and peaceful activities in the field of Iranian civil society, which teacher activists have demonstrated, is a rare phenomenon in the civil life of the past three decades. Many teacher activists have been arrested and imprisoned for long periods of time in the past years, but most of them have immediately returned to their civic-professional activities after their release, without any change in their approach or even their literature, or becoming more radical. Teachers have learned that civic activity in Iran is a very slow and gradual movement that faces many obstacles and requires a lot of patience and tolerance; the same characteristic that

The role of organization and structuring is irreplaceable.

The use of the right to protest and its continuation for nearly 15 years without proper organization and coordination was not possible. The first organized protest movement of teachers took place in Dey and Bahman 1380 (December and January 2002) and immediately after a few weeks, the first coordination meeting of trade unions was formed in Esfand 1380 (February 2002), which over the course of several years expanded into a wide network of 45 trade unions across the country. Teacher activists have used even the smallest opportunities to exercise their right to organize. Although most teacher unions were declared illegal by the government after the nationwide protests in 1386 (2007), the network of teacher communication maintained its existence through various innovative means (including economic and housing cooperatives). The construction of a professional-organizational identity has been one of the key and successful aspects of the teacher activist network in the past decade. Financial and moral support for imprisoned teachers and their families has been one of

Intelligence, courage, and responsibility of professional institutions such as the Teachers’ Guild and the Coordination Council of Cultural Guilds throughout the country, and of course the widespread use of technology and the capacity of networks and social applications have played a key role in shaping and sustaining recent protests.

The strategy of synergy and adopting a win-win approach.

In the early 1980s, a portion of the energy of teacher activists was spent on convincing officials of the education system to defend the right to unionize and engage in professional activities, and not see it as conflicting or competing with the missions of the education system. However, it seems that today at least some officials of the education system have come to the conclusion that the professional activities of teachers have added value and their lobbying abilities and soft power within the government structure, especially during important times such as budget planning, have increased.

On the other hand, union activists have been able to distance themselves from the government and political factions and adopt a two-party or non-partisan approach; meaning that both political factions within the ruling government have gained some level of confidence that the network of teacher union activists is not united with one political faction in moments of political conflicts. Achieving this level of confidence, of course, has been a slow and gradual process and has come at a heavy cost paid by teacher union activists.

***

During my time as a student, I always wondered why the song “My Elementary School Friend” has become a symbol of students and the academic movement, despite its focus on the classroom and school environment. It seems that a shift is taking place in Iranian civil society (or has already taken place). Along with this structural change, civil society is also undergoing a transformation in its content, form, and use of symbols. A symbolic example of this historical shift in Iranian civil society is the song “My Elementary School Friend,” which suggests that “the first stick” is also going back to the hands of teachers. If in the 1970s and 1980s, students or women were the flag bearers of Iranian civil society, without a doubt, the 1990s should be considered the decade of union activists and teachers.

Tags

Ahmad Madadi Childhood friend Monthly Peace Line Magazine peace line Right of assembly Teachers' Union ماهنامه خط صلح