The Women’s Conditional, 50 Years of Struggle / Elaheh Imaniyan

Nowadays, Iranian women can participate in elections; they have the right to vote and be elected as representatives in parliament. Iranian women have gained this right through a history of struggle and resilient resistance. As evidenced by history, in critical moments, women have stood side by side with men, but when it comes to sharing power, women and their demands have always been denied. One of the oppressions imposed on women was denying them the right to vote. In this context, I have taken a look at the half-century of women’s struggle for the most natural citizenship right; the right to vote and be elected.

According to history, Iranian women played an important role in the Constitutional Revolution. Their contribution was significant enough to be recognized and recorded in history. For example, in Azerbaijan, after the conflicts between supporters and opponents of the constitution, the bodies of 20 women dressed in men’s clothing were found. However, the fire of distrust between Iranian women and male lawmakers was ignited from the beginning of that historical period, when women who supported and followed the idea of the constitution were pushed aside. On October 7th, 1906, when the first National Assembly was formed and the election law was passed, women realized that male members of the assembly had ignored their efforts to gain a seat and had deprived them of the right to vote, along with criminals, lunatics, thieves, murderers, foreigners, and individuals under the age of 20. Thanks to the constitution that they fought for, women were left behind in determining their own fate.

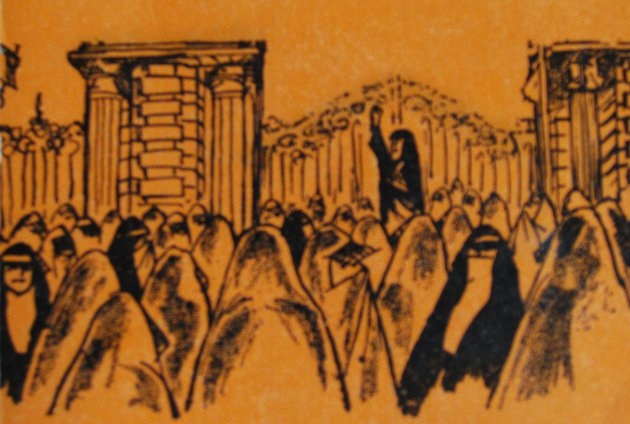

Women who had previously proven by their presence in the Constitutional Revolution that they would not sit back, rose up again. If I were a historian, I would call those struggles “Women’s Constitutional Revolution”. The protesting women believed that the “Constitutionalist men” had insulted them by considering them equal to the insane and children. This time, the protesting women, alone and without men, began the fight for their right to vote. Although at the time, the importance of women’s political participation was not fully understood by many; “in fact, the patriarchal culture of traditional Iranian society belittled women and considered them lacking in political element, limiting their activities to being wives and homemakers.” (Mohammadi Asl, 1383)

The first group to protest this issue was the “Society of Hidden Women” led by Sadigha Dolatabadi. Despite various protests, one year later on October 6, 1907, the National Consultative Assembly passed the Supplementary Constitutional Law and legally deprived women of the right to vote and be elected. After this, the male legislators boldly made their decision to deprive women of their voting rights and showed that their protests were useless. In fact, they showed that they were the ones making decisions and intended to dominate the political arena unilaterally.

In July 1908, Mohammad Ali Shah closed the parliament and it remained closed until mid-1909. After the closure of the parliament, the same women who had once been betrayed by the “Constitutionalist men” rose up again alongside the Constitutionalist men to fight. After the parliament was reopened, due to protests against the decision of the parliament to deny women the right to vote, this issue was brought up again in the parliament. In the midst of this, there were also men who emphasized the right to vote for women, but there was no room for acceptance in the parliament. Haji Mohammad Taghi Vakil Al-Ra’aya, representative of Hamedan, along with Taghi Zadeh, asked for women to be given the right to vote in the parliament. According to historical documents, it is said that Vakil Al-Ra’aya was the first man to speak in defense of women’s right to vote from the parliament podium, but he

Although the situation for women did not change in the second round of parliament, for example, one of the staunch opponents in parliament, Seyyed Hassan Modarres, expressed his opposition in this way: “Today, no matter how much we contemplate, we see that God has not given women the ability to deserve the right to choose… In fact, women in our Islamic religion are under the guardianship of men and our official religion is Islam, they are under guardianship. They will never have the right to choose. Others must protect the rights of women, as God says in the Quran, they are under guardianship and will not have the right to choose, neither in religion nor in the world. This was a matter that was briefly mentioned.” Finally, after various oppositions and discussions, the Election Law was passed in 1289. In this law, the first group to be deprived of the right to vote were women, followed by those who were outside of natural growth.

At that time, women were also busy pursuing their other rights, such as the ban on polygamy and the right to education. But among all the women who were striving for their rights, Sedigheh Dolatabadi was one of the few who had been advocating for women’s right to vote since the beginning of her activism. She had turned her newspaper, “Women’s Language,” into a platform for defending women’s right to vote and wrote various articles on the subject. In one of her articles titled “The Pen Was in the Hands of Men,” Sedigheh Dolatabadi protested against depriving women of the right to vote and wrote, “If women had the right to vote, they would not choose tyrants and oppressors like men do to deal with injustice and promote freedom.”

Sadegheh Doulatabadi spoke all the words and did not hesitate to express her protests. She also wrote an article titled “Elections” in Ardibehesht month of 1299 SH, stating: “…In the previous three terms, we, as women, did not see any results of the voters’ beliefs and the services of the elected officials. However, if our brothers were willing to listen to us, I do not hesitate to give them advice: …In our opinion, this is the reason why the nation has not experienced conditional happiness in the past 14 years. But if we, as women, had the right to choose our representatives, we would only choose from among our own people or those close to our people, anyone who is wise, knowledgeable, free-thinking, constitutionalist, patriotic, nation-loving, honest, and God-fearing. Through these kinds of representatives, who will undoubtedly be the first to think about laws and plans that will free the

After Reza Shah gained power, he visited Turkey in 1313. He followed the example of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the president of Turkey at the time, in making some changes and reforms. Some of his reforms in the area of women’s rights included allowing girls to attend universities and reforming marriage laws. He also imposed heavy fines for discrimination between men and women in public places such as cinemas and hotels. However, Reza Shah, in emulating Atatürk, paid more attention to superficial modernization; for example, he did not grant women in Turkey the right to vote in 1313 and did not pursue a similar action for Iranian women.

Despite all the challenges, women continued their activities to gain the right to vote. In 1321, Fatemeh Siah and Safieh Firouz founded the “Iranian Women’s Party”. This party focused primarily on obtaining women’s suffrage. If before this, other demands of women such as the right to education were pursued more, during this time, women’s suffrage became one of the most important demands that various women’s groups and associations pursued. Sadigheh Dolatabadi was also a leading figure in the fight for women’s suffrage. In another article in the “Women’s Language” magazine in Khordad 1324, she wrote: “What do you read in the first chapter of the Constitution? Women, madmen, and children do not have the right to vote… The writers of the law were shamelessly cruel to the women of Iran. By establishing the first chapter of the Constitution, not only did they lay the first brick cro

In continuation, in 1322, the women’s organization of the Tudeh Party was formed and in December of the same year, Tudeh Party representatives in the 14th Parliament presented a new proposal for the election law, in which women also had the right to vote. However, for several years, there were ongoing struggles surrounding this proposal and no results were achieved. Finally, this proposal remained silent until 1326. However, during this time, women only participated in elections once: when the Democratic Party of Azerbaijan, which had communist tendencies, elected a state government and for the first time gave women the right to vote. Thus, Azerbaijani women were the first Iranian women to be able to participate in elections. In 1326, while the previous proposal presented in the 14th Parliament remained silent, the Tudeh Party, which had 10 seats in Parliament, prepared a separate bill for women’s voting rights, which none of the other representatives were willing

Two years later, in 1328, Mehrangiz Manouchehrian wrote the book “Criticism of Iran’s Constitutional, Civil, and Criminal Laws from a Women’s Rights Perspective” and addressed the critique of the election law. In addition to Mehrangiz Manouchehrian, the “Iranian Women’s Party” and “Women’s Association” made efforts to obtain more voting rights.

Two years later, Mosaddegh, at the beginning of his prime ministerial term, drafted a bill that recognized women’s right to vote. This was met with strong protests from religious scholars, with the support of prominent merchants. Students took to the streets to oppose Mosaddegh’s proposal, resulting in one death and twelve injuries. The Islamic Fedaian and Ayatollah Kashani were among the staunch supporters of women’s voting rights. Ayatollah Kashani opposed the government’s decision to grant women the right to vote, believing that women should stay at home and fulfill their primary duty of being a homemaker and raising children.

In December 1952, Ayatollah Khomeini also officially declared his opposition to granting women the right to vote in an interview with the magazine Tareeqi. Eventually, with the rise of various protests, Prime Minister Mossadegh was forced to remove the provision for women’s suffrage from the draft of the election law. However, women did not give up on fighting for their rights; the Women’s Organization of the Tudeh Party wrote a letter to the United Nations, citing the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to protest against the removal of women’s suffrage from the draft of the election law. Copies of this letter were also sent to Dr. Mossadegh and the parliament.

After the coup of 28 Mordad, new associations began to work towards women’s demands. In 1334, “Jameiat-e Rah-e No” (New Path Society) was founded by Mehrangiz Dolatshahi, and in 1335, a group of women including Farrokhro Parsa, Safieh Firouz, and several others formed the “Council for Women’s Cooperation in Iran”. One of the actions of this council was welcoming the Shah at Mehrabad airport in 1336 upon his return from a trip to the Soviet Union with a placard that read: “We demand equality for Iranian women’s rights”. After that, this council submitted a list of 11 demands to Mohammad Reza Shah, which included granting women the right to vote in council and senate elections.

These activities did not have any impact on the court and ultimately led to the formation of the “High Council of Women’s Society” in February 1959. This council had set its goals to pursue the demands of women. Ashraf Pahlavi took over as the head of this council. Despite all of this, Mehrangiz Manouchehrian was still one of the prominent faces in the fight for women’s suffrage. She, who had previously written the book “Criticism of Iran’s Constitutional, Civil, and Criminal Laws from the Perspective of Women’s Rights,” founded the “Women’s Union of Lawyers” in 1961.

It was the year 1339 and the time for elections had arrived again. Twenty rounds of National Assembly elections had passed, but despite the efforts of women, they had not yet been successful in gaining the right to vote due to opposition and numerous obstacles. The election was a good opportunity for women to voice their demands once again. Therefore, various women’s associations published a joint statement and called for women’s participation in the elections. At this time, the staunch opponents of women’s participation in the elections were Abolghasem Falsafi, a well-known preacher in Tehran, and Ayatollah Boroujerdi, a religious authority. Women had set up a tunnel in front of the Senate building, through which senators had to pass and witness their protests and placards. Finally, the elections were held and once again, women were left behind.

In 1341 (1962-1963), during the prime ministership of Assadollah Alam, the bill for state and provincial associations was approved. According to this bill, women were allowed to participate in elections for the first time and could also run as candidates for state and provincial associations.

Ayatollah Khomeini formed a meeting in Qom in this regard, and afterwards sent a telegram to Mohammad Reza Shah, protesting with a three-point bill from the state and provincial associations, including granting the right to vote to women. The Shah delegated the decision-making in this matter to Assadollah Alam, who in a speech considered the opposition to this bill reactionary. However, with the rise of protests from clerics and religious authorities, including Ayatollah Shariatmadari, Ayatollah Milani, Ayatollah Golpayegani, and at the forefront Ayatollah Khomeini, in less than two months, Alam announced that this bill would not be implemented. Women’s associations, in protest against the withdrawal of this bill, on January 7, 1963, instead of going to the shrine of Reza Shah as usual, took refuge in front of the Prime Minister’s office and were met with force. We see that every time, for whatever reason

Finally, on January 19, 1962, the Shah announced his famous 6-point plan known as the “White Revolution of the Shah and the People”. The fifth point of this decree was the bill for electoral reform. It was planned to hold a referendum on February 6th to decide whether or not to implement this plan. Women saw this as an opportunity, quickly took action, and once again took the initiative. The representative of the “Women’s Union of Lawyers”, led by Mehrangiz Manouchehrian, went to see the Minister of Agriculture and the person in charge of implementing land reforms – which was the first point of the referendum – the night before the referendum and asked him about women’s participation in the referendum. He had replied that he saw no problem with women participating in the referendum. While the government had not yet spoken about allowing or not allowing women to participate in the referendum, women, by asking the minister and receiving an answer from him, created this

On 12 Esfand of 1341, the government officially announced that Article 13 of the election law, which prevented women from participating, and the words “men” from Articles 6 and 9, which were related to candidate qualifications, had been removed. Therefore, women were granted the right to participate and to be elected; after 57 years of tireless struggle, they finally obtained the right that had been taken away from them in the Constitution. Women lost 57 years of opportunity to gain experience in the political field, but they gained 57 years of experience in resistance and civil activism. On 21 Shahrivar of 1342, with the support of half a century of valuable struggle by Iranian women activists, six women entered the parliament for the first time and two women, Mehrangiz Manouchehrian and Shams al-Molouk Mosaheb, became the first female senators in Iran.

However, we see that despite the access to the right to vote and the right to be elected as a representative in parliament, there are many challenges facing women. The Inter-Parliamentary Union has mandated all member countries to have at least 30% of parliament members be women, but in Iran, this number does not exceed 3%. The field of equal political participation, joining political parties, and reaching positions of policy-making is still accompanied by many obstacles and difficulties for women, and the tireless struggles of Iranian women to uphold their rights in various fields, including politics and management, continue for the advancement of the status of women in society and equality.

Sources:

1- “Abrahamians, Yerevan, Iran between two revolutions, translated by Ahmad Gol Mohammad and Mohammad Ebrahim Fattahi, 12th edition, Ney Publishing, Tehran 1386.”

2- Ahmadi Khorasani, Noushin and Ardalan, Parvin, Senator; The Activities of Mehrangiz Manouchehrian in the Field of Women’s Legal Struggles in Iran, Tous Development Publications, Tehran 1382.

3- Sanasarians, Elise, Women’s Rights Movement in Iran; Rebellion, Decline, and Suppression from 1280 to the 1957 Revolution, translated by Noushin Ahmadi Khorasani. Akhtaran Publishing, Tehran 1384.

Women’s Language, Issue 23, First Volume, 12 Shaban 1338 AH (lunar)

Language of Women, Issue 12, 23 Shaban 1338 AH (Hijri Lunar Calendar)

6- Mashirzadeh, Hamira, From Movement to Social Theory; A History of Two Centuries of Feminism. Shirazeh Publishing and Research, Tehran, 1381 (2002).

Created By: Elahe Emanian

Created By: Elahe EmanianTags

Condition Goddess of faith Monthly magazine number 55 Monthly Peace Line Magazine