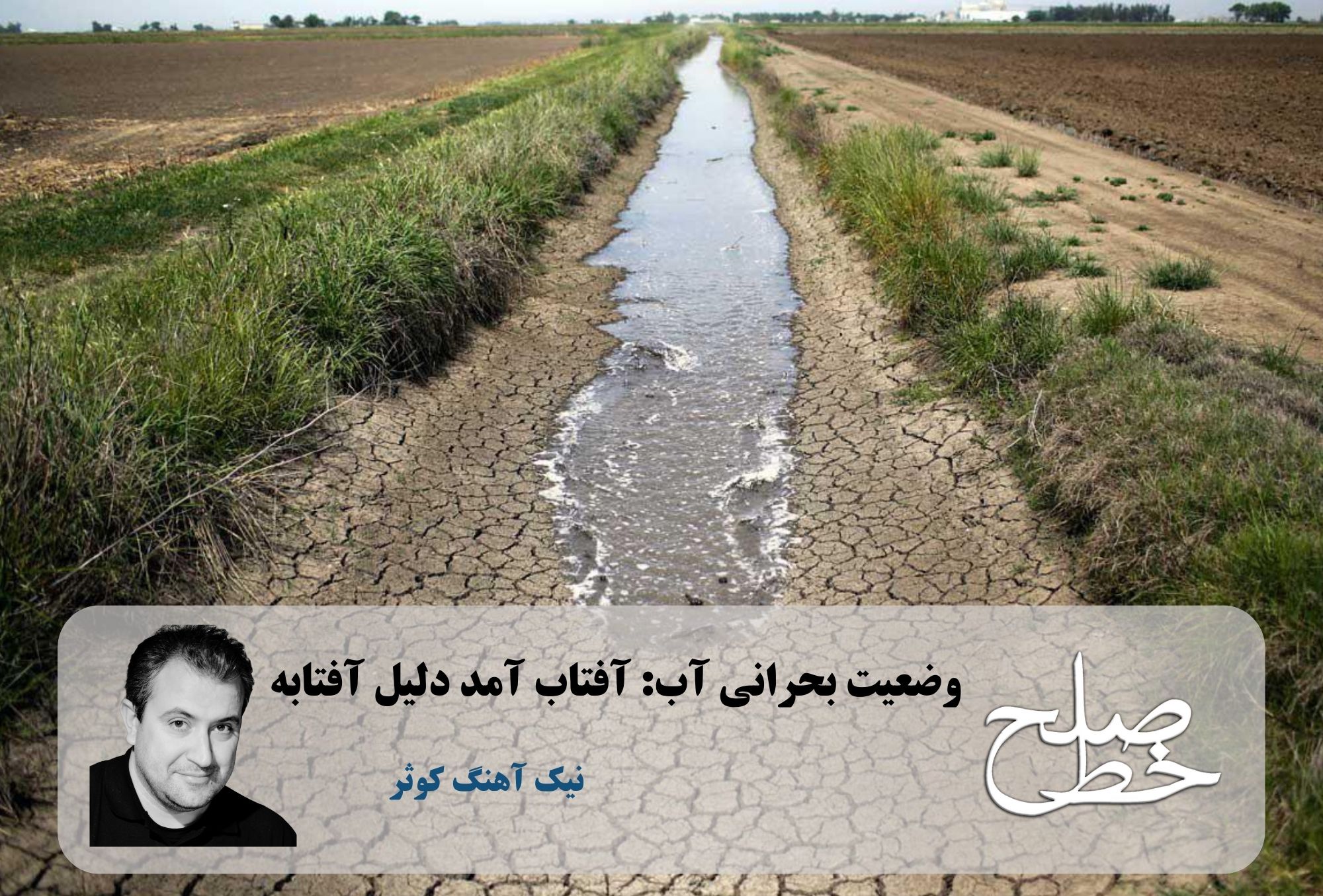

he Water Crisis: The Sun Proves the Watering Can / Nikahang Kowsar

Perhaps no object better illustrates water governance and management in Iran than the “aftabeh” (watering can). It is unclear exactly to which monarch’s era the historical origins of the aftabeh go back, but the mere mention of it brings to mind, for many, the image of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini—a photo taken months before his return to Iran.

The aftabeh in Iranian culture and popular literature carries a range of meanings—from a sanitary tool to a symbol of social class. Those who owned copper or brass aftabeh and washbasins boasted over those who did not. Those who had ornate aftabeh and washbasins but no food on their tables represented meaningless, empty luxury. The “aftabeh thief” would be dragged before the judiciary, but the “crown thief” would be crowned. From another perspective, the aftabeh is a useful item—until it cracks. Clinging to a broken and leaky aftabeh is hardly a sign of rationality.

The aftabeh—be it copper, gold, or plastic—is ultimately a hollow container. If there is no water, it serves no purpose. “Aftabeh-style management” at a time when there is no water has endangered the lives of Iranians. But how did it come to this point, where the rulers’ aftabeh has ended up in such a state—while much of the intellectual elite has remained distracted elsewhere?

The excessive contradictions in the Islamic Republic era are rooted in the denial of knowledge and disregard for realities. The rulers have proven that their wisdom lies in their dim eyesight, paying no mind to the future of the country. When, in 1988 (1367), the Mousavi government was warned about the future of water resources in the coming decades, neither the groundwater tables had yet been depleted, nor could anyone imagine dried-up dams and cities and villages being supplied by tanker trucks. Since I had a hand in translating a report presented to the cabinet in Aban 1367 (October–November 1988), I know that the water security report by Joyce Starr and Daniel Stoll prompted some ministers to begin thinking. But the very next year, those same ministers foolishly embraced ideas of dam building, water transfer, and agricultural self-sufficiency—beyond all reason. Perhaps they adopted this approach to preserve their position in the new government—the so-called “reconstruction cabinet”—and thus accepted the idea that water governance must be based on a “hydraulic mission.” According to proponents of this view, water must be controlled and managed at any cost—to hell with the environment. Their solution lies in dam construction and inter-basin water transfer tunnels. They believe in top-down decision-making, coupled with one-sided propaganda, and consider development to be justified at any cost—without informing the public of the destruction of rivers, lakes, aquifers, and soil.

Since last autumn (Mehr 1403 / October 2024), when rainfall saw a noticeable decline, experts have grown increasingly concerned. While conservation in various sectors and proper planning could have reduced growing pressure on water resources, the water pressure in urban pipes was not reduced, and the illusion of water abundance in many citizens’ minds prevented them from recognizing the reality of their cities’ water savings accounts—i.e., aquifers—and the minimal water in their checking accounts—i.e., reservoirs—failed to convince them to prepare for periods of scarcity. But why hasn’t our collective wisdom steered us toward the necessary path?

Iran’s educational and social development systems since World War II have evolved in a way that ignores reality and has grown numb to hardship. While families once struggled to access water, today, most Iranians no longer need to travel miles for clean water—it is readily available. This very access to clean water, which could be better used and more equitably distributed over a longer period, is often taken for granted. Many people believe that since they pay for it, they can use it however they wish.

But not all societies are like this. Two years ago, while attending a conference in Cape Town, South Africa, I came across a written notice in my hotel room that read:

“Please limit your shower to 2 minutes. Water is scarce – thank you for saving it.”

And:

“If not necessary, do not flush.”

I later realized that the two-minute shower was a widespread policy in Cape Town.

From 2015 to 2018 (1394 to 1397), Cape Town experienced a severe drought, and only through public cooperation and citizen trust in local government, city officials, and water managers was the crisis averted. Many around the world became familiar with the term “Day Zero” during that time—the day when all municipal water pipes were expected to run dry and only air would come out of the taps.

By February 2018, when the risk of losing water became very real, Cape Town residents knew that each person’s daily water usage must not exceed 50 liters.

The key point was that most citizens trusted their local government, experts, and managers, and understood that if the water issue wasn’t resolved, there would be no choice but to leave.

In November (Aban), when Masoud Pezeshkian warned that if rain didn’t come at the right time, the water supply situation could force many to leave the capital, some laughed it off, while many others grew anxious. But poor management, lack of trust, and absence of any exit strategy from the crisis only added to public anxiety. Still, the bigger question remains: If it rains in the mountains, will that solve Tehran’s water problem?

Given what has happened to Tehran’s groundwater resources, the answer is no. Groundwater in the capital region provides over 60% of Tehran’s water needs, while surface water accounts for less than 40%. Nonetheless, investments in surface water supply and maintenance have far outweighed efforts to recharge groundwater. Authorities have neglected groundwater replenishment programs through poor urban planning, reduced ground permeability, and failure to implement urban aquifer management systems.

Also, the lack of proper wastewater recycling systems has resulted in the waste of highly valuable resources. Considering that planned wastewater treatment in some countries has reduced the need for inter-basin water transfer, the question arises: why do state institutions that claim to care about public health spend massive budgets on projects that, due to shifting rain and snow patterns in coming years, will likely be rendered unviable—while they could allocate those funds to large-scale recycling programs that would both meet significant water needs and uphold citizens’ right to sanitation?

Water governance in the Islamic Republic is emblematic of the broader governance structure in the country: top-down decision-making, executive orders based on rulers’ whims, indifferent to real needs, and aimed at pleasing segments of the security apparatus.

The Million-Dollar Question: Who Can Solve the Water Crisis?

Masoud Pezeshkian stated at the beginning of summer that he would award 100 billion to whoever solves Iran’s water crisis. Let’s assume he meant 100 billion tomans, which, at current rates, is about 1 million U.S. dollars.

Solving the water crisis is beyond the capacity of any one person. Water is a complex issue involving various actors and scenarios. As game theory experts suggest, given the constantly changing conditions, water issues must be viewed and examined within the framework of complex systems.

The bigger question is: Can a single country solve Iran’s water problems? Suppose Iran handed over all its water affairs to Israel—would the problem be solved? No!

I often remind my friends of the words of Shimon Tal, Israel’s highest-ranking water official between 2000 and 2006. He used to say that one should not “copy-paste” Israeli methods, but rather understand the logic and thinking behind their water management. Instead of imitation, one must examine what analyses of needs and shortages led to specific solutions. According to Tal—who has worked with the World Bank—Israeli water managers review and revise the national water plan every five years by tracking their own mistakes and shortcomings.

If a plan were truly flawless, there would be no need for updates and corrections. So even if we were to copy one of Israel’s newest projects today, how do we know they won’t discover major flaws in it a few years down the road? The very flaws that have already driven the Jordan Valley into water poverty, pushed the Dead Sea toward destruction, and created thousands of sinkholes around it.

More importantly, some Israeli water experts advocate solving the water problems of Palestinians—but for countless reasons, their voices are almost never heard in the media. Instead, we mostly hear from Israeli politicians, who fundamentally have no right to interfere in water management. That’s a contradiction. I prefer the words of Shimon Tal and those like him.

But without decentralization in water governance and management, the problems cannot be solved. No project should proceed without an environmental impact assessment. Iran’s aquifers cannot be ignored, desalination should not be forced upon the country under the guise of development, and aquifer management should not be abandoned. Illogical agriculture must not continue—but farmers should not be driven out of work either. Ignoring those who provide the people’s bread is foolish—biting the hand that feeds.

We cannot focus solely on water supply without implementing conservation and austerity-based management. Efficient water use must be practiced as part of water management!

We must not justify excessive and foolish water use in dry areas under the pretext of creating green spaces by planting lawns and high-consumption invasive species—and then refuse to be held accountable.

We cannot leave broken, leaky water infrastructure unrepaired and merely ask people to reduce consumption.

We cannot develop water-intensive industries in water-scarce regions like Yazd, Mashhad, Shiraz, and Isfahan—and then hypocritically ask the people to take water scarcity seriously.

A comprehensive perspective is essential.

Tags

Air pollution Drought Good song of Kowsar peace line Rainfall Time saving Water crisis Water scarcity Without water ماهنامه خط صلح