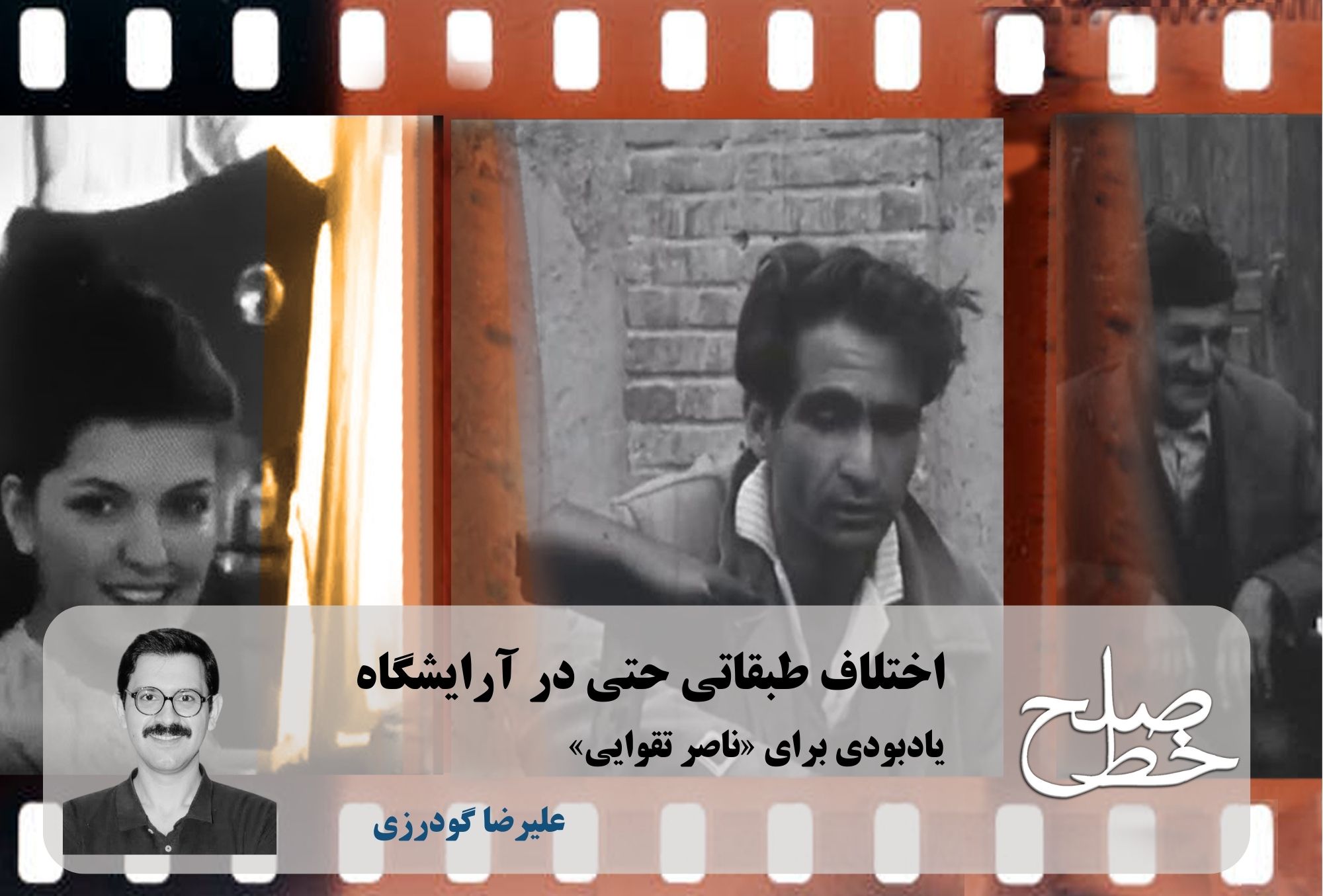

Class Divide, Even at the Barbershop/ Alireza Goodarzi

Last month, Nasser Taghvai passed away. For our generation, Taghvai was a director whose every film was made with a precise and committed eye on society, and the stunning details of his work spilled beyond the frame of cinema and television. For decades now, some of the catchphrases from his TV series Dāyi Jān Napoleon are still used in everyday speech. Had Iraj Pezeshkzad’s masterpiece not been brought to the screen by Taghvai, it might never have entered the collective memory of Iranians. May both their memories be honored.

Taghvai also worked in documentary filmmaking, and with the same attention to detail, he pursued topics that were uniquely his own. In all of them, there was a sharp focus on social dynamics. One such film was a short titled Sunshine Barbershop. And it really is a short film—less than ten minutes long—concise, relatable for everyone, and without a single scene or word that could be added to or taken away from.

We’re used to recognizing class disparity through neighborhoods and homes, cars, clothing, and food. But its manifestations go beyond these. Perhaps no one could have captured one such rarely considered form better than Taghvai. The film opens with a Bayat-e Tehran song to immediately set the scene. Images flash by of barbershops offering luxury services, all without narration, and then we are brought to the street-side barbershops.

The first thing that might strike a modern viewer is the lack of hygiene. A place beneath the open sky, under the direct sun, using the most basic tools—where one plainly dressed man grooms the face and hair of another, equally plainly dressed. There’s no hair dryer, no magazine with a woman on the cover. People haggle over price and tidy themselves up for a small fee.

But the class divide—or center and margin, or whatever we choose to call it—doesn’t end there. Taghvai includes a few brief interviews with these barbers, who have come to Tehran from other cities to make a living. They say there are no street barbershops in their hometowns, and that in Tehran they can work—just enough to scrape by, as one of them puts it, explaining how he left home behind and now works under the scorching sun. Meanwhile, there’s not a single word heard from the upscale barbershops. Taghvai doesn’t offer both groups equal opportunity to speak—because, fundamentally, these two groups don’t have equal opportunity in life. His decision is to give voice to those who have had fewer chances in society.

Given the lack of precise statistics in 1967 (1346), the year this film was made, it’s difficult to find any reliable index of inequality in Iran at that time. It seems that in the decades that followed, inequality slightly decreased, but it undeniably still exists and continues to ravage society. Meanwhile, during these decades, Taghvai worked less and less, and his camera no longer captured poverty and wealth, the contrast between barbers and customers from two different classes, or the difference between “Shazdeh Asadollah” and “Shir Ali the Butcher.”

Taghvai’s other documentaries also show his keen eye and sensitivity to human life. Beyond his more famous works, which are known to many, his documentaries offer admirable details of the simple, everyday lives of people. Perhaps his greatest artistic strength can be seen in his documentaries about Iran’s southern regions.

His film Minab Thursday Bazaar presents striking images of Minab and the traditional lifestyles of its people, showing a filmmaker’s sensitivity to a phenomenon that, in the era of Iranian modernization, few paid attention to. For those of us visiting Minab in a completely different era, the visuals of the environment—especially its people—are mementos left behind by Taghvai’s camera, capturing a centuries-old tradition that has since changed significantly over time (if interested, listen to the Megoon podcast episodes on Minab and its Thursday bazaar).

Also, the 1969 (1348) documentary Wind of Jinn (Bād-e Jen) can be viewed alongside Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi’s ethnographic account of winds and zār rituals—his book People of the Wind—as the best source for understanding this phenomenon within its traditional context. Such documentaries are invaluable, especially in our time, when such ceremonies are disappearing or undergoing significant transformations before they can even be visually documented. For Taghvai, human beings and their lives—regardless of origin or birthplace—were inherently interesting, and his camera saw the Rashti barber in Tehran, the bear-handler in Minab, and other simple facets of life with great clarity. He also saw and revealed class disparities with care, unlike many of his contemporaries who preferred to portray a particular class—those with cars and privilege—or romanticize poverty as colorful and heroic.

This brief note, under the pretext of class inequality, is a tribute to Nasser Taghvai. Please watch his short film, and recommend it to others as well.

Tags

Alireza Goodarzi Cinema Class division Naser Taghavi peace line Social stratification ماهنامه خط صلح