From Execution Square to the Square of Distrust/ Majid Shia’Ali

After several decades of failure in economic development, democratization, and the strengthening of human rights observance, our society is now looking back at its previous experiences. Our society sees that despite experimenting with various revolutionary and reformist strategies, from parliamentary methods to violent confrontations, and experiencing multiple revolutions and social movements, it has still not achieved its desired outcomes. Alongside a growing sense of despair, a question arises in the minds of Iranians: What were the reasons behind the failure of these various approaches? Why have we still not managed to attain democracy, human rights, and sustainable economic development? One of the answers currently circulating among thinkers and concerned individuals is the emphasis on a particular component: that we have a weak civil society and low social capital. But what exactly is meant by this low social capital?

Contrary to the popular perception among Persian speakers, when we speak of social capital, we are not referring to influential and prominent figures in society, but rather to a kind of asset. The first theorist to seriously use this term in his thought was Pierre Bourdieu. With his Marxist mindset aiming to analyze class conflict within societies, Bourdieu used this term to identify a specific type of capital. He argued that the only capital accumulated in the hands of capitalists is not economic capital; there is another form of capital that can be converted into economic capital. Social capital is created based on the social relationships an individual has with others. This network of social relations, like a form of capital, can influence an individual’s economic gains. It can be invested in and increased. From Bourdieu’s perspective, social capital—like economic capital—is also concentrated in the hands of capitalists. They possess familial or friendly connections that assist them in future activities and distinguish their lives from those without such strong networks. The child of a wealthy family is likely to attend schools with other children of capitalists, build friendships with peers who will later become influential, and benefit from these networks for future advancement. Furthermore, they belong to families with good access to various resources and can use those due to family ties. They also join friendship clubs that strengthen these networks. On the other side of the spectrum, the children of weaker social classes have networks that lack resources at this level.

However, the use of the concept of social capital became more widespread through the work of another thinker. In the 1990s, Robert Putnam introduced this term into public discourse. In his view, the focus was less on individuals’ social capital and more on the social capital of groups and communities. This means that a group, due to its level of connectedness, mutual trust, shared norms of collective work, and so on, can achieve its goals more effectively. As he states: “By social capital, I mean those features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.” To better understand his point, imagine a team in which members have a high level of trust, cooperation is considered a core value, and there are complex and extensive friendship networks. Now compare that to a team lacking high trust, proper norms, and broad communication networks. It is easy to guess that the first team would achieve better results at lower costs. This perspective is also applicable at the national level. A society where people have more trust in one another, where norms facilitate cooperation, and where a wide range of formal (civil, political, labor organizations, etc.) and informal (sports groups, book clubs, friendship gatherings, etc.) connections exist, can achieve more with less cost.

This idea has attracted the attention of both 19th-century thinkers like Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill—who emphasized the importance of a society with various associations as the foundation of democracy—and more recent research which highlights its significance across various domains.

Various studies emphasize three key points: First, societies with higher levels of social capital experience greater economic growth; second, democracy is a product of societies with higher levels of social capital; and third, even health indicators are higher in societies with more social capital. Given the wide-ranging impact of social capital and the broad spectrum of problems we face, one could argue that the low level of social capital in Iran is a root cause of our various challenges. Therefore, it demands special attention.

In his famous work Bowling Alone, Putnam argued that the level of social capital in the United States declined over the decades leading up to the 1990s. He attributed this decline to the expansion of television and lifestyle changes: instead of joining local bowling teams or political parties, people sat on couches staring at their televisions. With the advent of the internet and social media, this deterioration of social capital has accelerated globally. Iran is no exception. Another factor affecting social capital in Iran has been the experience of authoritarian rule. Various studies show that people in Eastern European countries, after enduring decades of authoritarian governments, have lower levels of social capital compared to their Western counterparts. To these two factors, we must add economic stagnation. Research also shows that European countries experienced such a destruction of social capital after the 2008 economic crisis that they have not yet recovered to pre-crisis levels. Based on this, it can be surmised that more than a decade of economic stagnation and sanctions in Iran has severely impacted the level of social capital. For all these reasons, it is likely that our country has suffered from an undesirable level of social capital in recent years, and due to the importance of the matter, we are in need of rebuilding it.

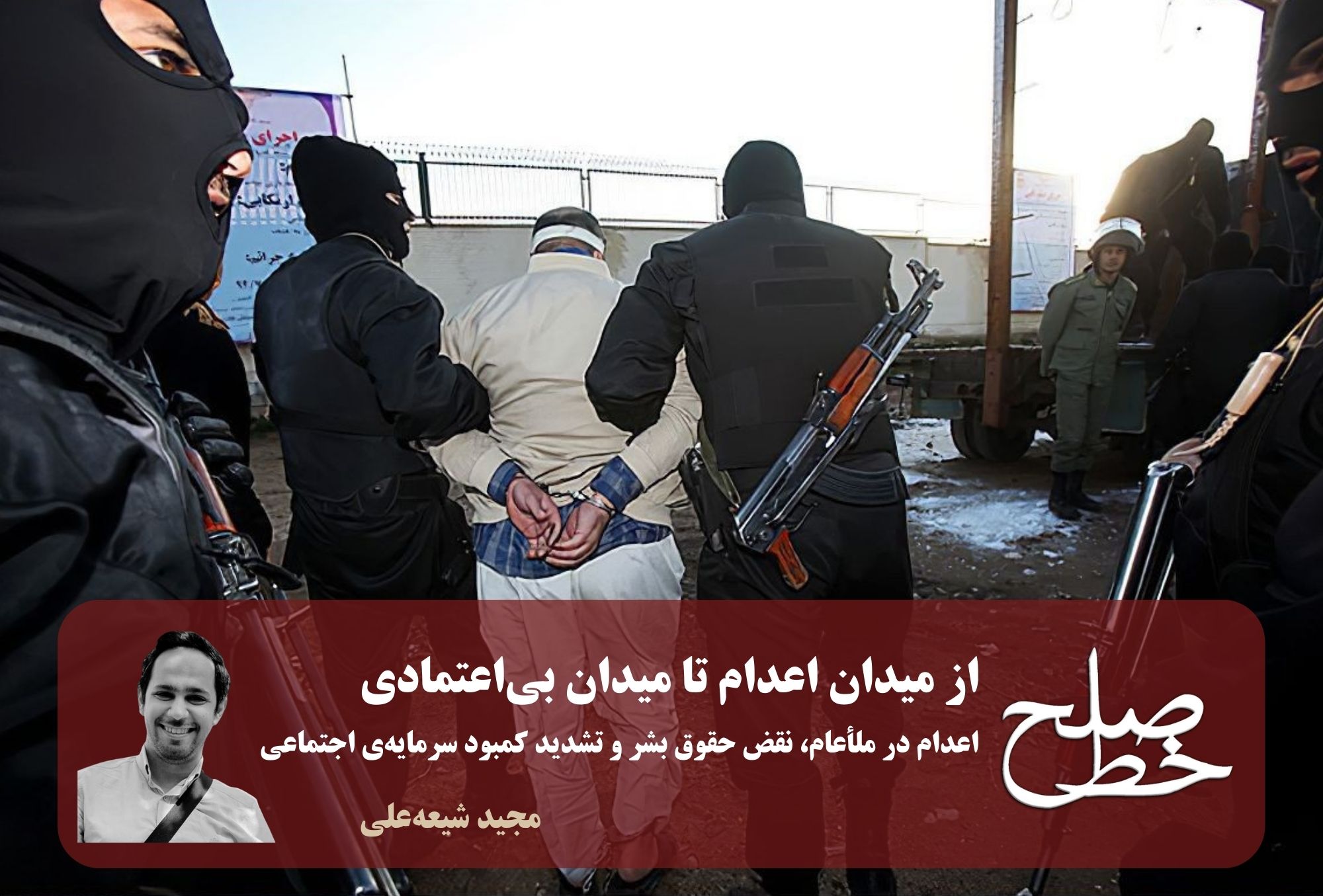

But the issue begins with this question: Do extremely violent actions by the judiciary—such as executions, especially in public—have an impact on social capital in Iran, apart from the fact that they are intrinsically a violation of human rights? In other words, does this violation of human rights lead to a reduction or at least a stagnation in the growth of social capital in Iran, and does this affect democratization and development in the country? To answer this question, we must examine two key issues: First, what is the relationship between violence and social capital? And second, does the judiciary’s performance impact social capital?

As might be expected, numerous studies have shown that social capital and violence (more specifically, homicide) have an inverse relationship in societies. That is, in contexts where homicide rates are high, social capital is very low, and conversely, higher social capital is associated with lower murder rates.

The next question is about the causal relationship between these two components. Is it that violence in society reduces individuals’ trust in one another and weakens formal organizations and informal networks? Or is it the low level of social capital that creates the conditions for violence and homicide? Sandro Galea and his colleagues studied the correlation between these two phenomena in the United States between 1974 and 1993 to determine the causal relationship by examining changes over time. They discovered a bidirectional relationship: both the increase or decrease in social capital can affect the likelihood of future homicides, and the rise or fall of violence can influence the level of social capital. However, among these, the more influential factor was the rate of homicide. In other words, increased violence is more likely to affect social capital than vice versa. Therefore, it can be assumed that the experience of blatant violence by a governmental body in a public square severely harms the social capital of Iranians.

In another study, Rothstein investigated the impact of government quality on social capital and measured how public trust in government affects social capital. He distinguishes between two parts of governance: one that includes politicians, parliament, the cabinet, and others, which citizens see as their representatives; and another that includes the judiciary, law enforcement, and similar institutions, which are expected to enforce the law. While trust in the first group does not significantly correlate with the level of social capital in societies, trust—or lack thereof—in the second group has a direct and serious effect on social capital. Rothstein writes: “Generalized trust is built upon trust in the impartiality and fairness of public [judicial] institutions and shapes most people’s trust in each other.”

Therefore, in a context where a significant portion of our society opposes all forms of execution and views it as a clear violation of human rights—especially when carried out publicly—such actions are seen as a blatant injustice by the judiciary and a grave crime. It can be assumed that increased distrust in the judiciary resulting from such actions leads to a decrease in interpersonal trust in society and damages the social capital of Iranians.

Based on the above, and due to both reasons—the promotion of state violence in society and the blatant display of injustice at the highest level by the judiciary—we are likely witnessing the serious destruction of social capital in Iran due to such actions. In effect, the already low social capital in the country is further eroded, and as a result, even the limited opportunities for democratization, economic growth, and development are lost. Thus, it must be stated that such actions are not only a blatant violation of human rights, but also inflict irreparable damage on Iranian society.

Tags

Distrust in relationships Execution Execution in Malaam Execution punishment Majid is a Shia follower of Ali. Majid Shia Ali Murder peace line Peace Line 173 Public execution Punishment Reproduction of violence Right to life Social capital Violence ماهنامه خط صلح