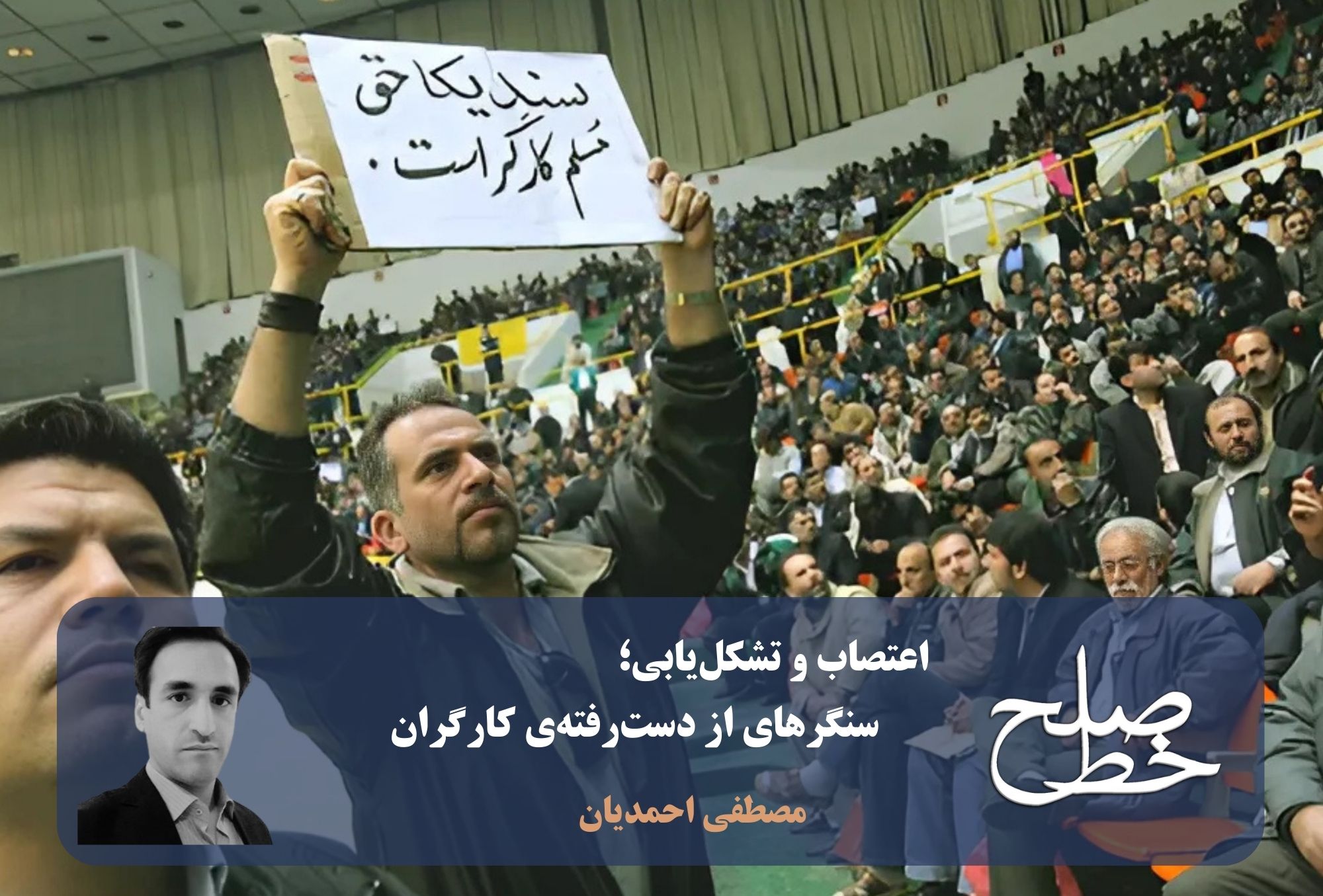

Strikes and Organizing; The Lost Fortresses of Workers / Mustafa Ahmadian

Nearly a century has passed since the fourteen-day nationwide strike of printing workers and the prolonged strike of oil industry workers in Abadan between 1300 and 1404 (1921-1925). These were the first genuine and official strikes in the labor movement in Iran. Subsequently, between 1304 and 1320 (1925-1941), widespread strikes occurred, which faced the harshest attacks from Reza Shah’s regime, targeting national parties and progressive unions. These attacks culminated in 1310 (1931) with the passing of the Law on the Punishment of Conspirators Against National Security and Independence, also known as the “Anti-Communist Law” or the “Black Law,” which intensified the security atmosphere and the repression of national and labor movements.

However, following the decline of the first Pahlavi regime, the years 1320 to 1332 (1941-1953) can be considered a period of flourishing for the Iranian labor and union movements. This period coincided with the expansion of machine industries and the growing number of workers, leading to the establishment of the Central Council of United Workers’ and Toilers’ Unions in 1323 (1944) and the passing of Iran’s first labor law in 1325 (1946) by the National Assembly.

The United Workers’ and Toilers’ Unions, with over 300,000 workers under a unified banner, enjoyed international support and laid the foundation for significant strikes and labor movements during that time. The six-day strike of 1,000 workers at the Kermanshah oil refinery and the massive strike of thousands of workers in Aghajari in 1324 (1945) were among the most important events of this period, which also carried political demands, opposing American and British forces. Ultimately, this movement faced extensive attacks and clashes with the Central Council of United Workers from 1327 to 1329 (1948-1950) by the ruling powers, in collaboration with American and British forces. This led to the banning of union activities under the pretext of the attempted assassination of Mohammad Reza Shah, and the continued repression of the labor movement saw large-scale strikes and bloody protests, resulting in the deaths of eighteen people, including three children, according to some historical accounts. The major achievement of this period was the passing of the law nationalizing the oil industry in 1332 (1953).

The years leading up to and immediately following the 1979 revolution—from 1355 to 1360 (1976-1981)—marked a second period of flourishing labor movements. After the revolution, two groups of labor organizations became active in the country. The first were the labor unions, which, drawing on their previous experiences, continued their activities and reorganized in the new, more open environment. The second were the labor organizations emerging from the revolution itself, which saw controlling and organizing the workers as part of their revolutionary mission. After the passing of the law establishing Islamic labor councils in 1363 (1984), labor strike centers fell into the hands of revolutionary committees, and labor organizations were dissolved one by one. Union offices and protest sites were taken over by revolutionary forces, eventually leading to the establishment of the Workers’ House and the passing of the Labor Law in 1369 (1990), which, in some respects, was a clear regression from the earlier labor laws of 1325 and 1337 (1946 and 1958).

Since the passage of the latter law, the management of labor affairs for three decades has been in the hands of individuals such as Alireza Mahjoub, Hossein Kamali, Ali Rabiei, Abolghasem Sarhadi Zadeh, and Ahmad Tavakoli, all of whom went on to hold key ministerial and high-level positions in the country.

Aside from the tumultuous conditions of the 1980s, the resurgence of labor protests in 1396 and 1398 (2017 and 2019) marked the beginning of a new phase of worker subjectivity and consciousness, sparking a renewed spirit of independent labor protests. The peak of this could be seen in the Mahsa movement in 1401 (2022), especially in the new era that followed in the past two years, which continues to this day, as workers have not abandoned the streets. Over the past two years, some reports have recorded more than 1,460 large-scale labor protests and strikes, with widespread protests by various labor groups and retirees occurring in just Shahrivar 1403 (September 2024).

In analyzing labor law with a historical approach to the goals and principles of labor movements over the past century, the overall Labor Law passed by the Expediency Discernment Council in 1369 (1990) can be viewed as rooted in an idealistic and purely religious perspective. In this view, workers’ rights and priorities are subordinated to the Islamic model of wealth production, earning lawful sustenance, and defending productive foundations, rather than the defense of workers’ rights.

In the Labor Law, contrary to International Labour Organization Conventions 87 and 98, workers’ rights to strike, protest, and unionize are either prohibited or entirely unrecognized. The right to form unions and independent associations is only defined and interpreted within an Islamic and jurisprudential framework. Whenever the subject of organizing comes up, it is limited to joining one of the Islamic labor councils, guild associations, or workers’ representatives, all of which are overseen by government officials. The regulations and statutes governing these organizations are entirely drafted and regulated by state bodies and the Ministries of Labor, Health, and Interior, and these unions and associations are largely dependent on government and supervisory agencies. This can be inferred by reviewing Article 130 and subsequent articles of the Labor Law.

Although Article 26 of the Constitution recognizes the right to peaceful assembly, protest, and demonstration, the Labor Law makes no reference to this important right. These rights, however, are essential tools for workers in bargaining, organizing, and advocating for their demands against employers, industry owners, and governments, and they are vital to workers. Thus, one of the main criticisms of the labor system is the failure to adhere to the Constitution in all tangible and practical matters regarding workers’ rights. Issues such as free education, social security, free healthcare, the right to adequate housing, and the right to peaceful assembly and independent unions are acknowledged in the Constitution, yet find no suitable reflection in the Labor Law.

Article 7 of the Labor Law and its two associated notes also endanger workers’ job security. According to Note 2 of this article, in cases of ordinary, continuous work where a time period is specified in the contract, the contract is deemed temporary. This contradicts the logic accepted in Note 1 of the same article, and the prioritization of temporary contracts over continuous work is neither logically nor legally justifiable. This has led to widespread unemployment and the dismissal of many workers, as employers exploit the temporary nature of work contracts. Even the General Board of the Administrative Justice Court confirmed the temporary nature of these contracts in its unified decision 179, issued on November 12, 1996.

Another flaw in the Labor Law is its exclusion of many of its provisions from workers employed in free trade zones. This leads to the daily exploitation of more than one million workers engaged in hazardous and physically taxing jobs under the worst living conditions in these areas, where employers easily evade their obligations to these workers.

The scope of the Labor Law’s exceptions extends much further, encompassing Articles 120, 188, 189, 190, and 191, allowing for deviations from its general principles. Foreign workers, those engaged in various agricultural sectors, individuals covered by special laws, and workers employed in workshops with fewer than ten employees are excluded from the law’s coverage.

The Labor Law also has shortcomings in terms of the lack of protective mechanisms for workers, a lack of transparency in drafting contracts, the absence of oversight over verbal agreements, and the lengthy process of handling disputes in dispute resolution forums.

Therefore, the current laws have fallen behind the demands and transformations of the times, particularly concerning the inadequacy of wages, the lack of alignment between salaries and living costs, and the rampant exploitation by employers and industrial owners, all of which impose a double burden on workers and exacerbate the irreconcilable conflict between labor and capital.

Given all these problems, the emergence of recent protest movements is not coincidental; it is born of an essential and material need grounded in reality. Over the years, the labor force has encompassed the widest range of classes and social groups. If in the 1980s and 1990s the protests were limited to certain groups, such as the Syndicate of Workers of Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company and teachers, today all segments of society suffer from dissatisfaction and the deepening class divide, and every individual or group under any labor, contractual, or employment law finds themselves in genuine connection with the broader protest movement of the working class.

The government and legal responses to these growing demands have always been inadequate, uncertain, and disappointing. These legitimate demands have accumulated and taken on a nationwide dimension, in some cases even aligning with global labor movements.

Existing labor movements, aside from the Workers’ House and co-opting groups that do not represent workers, are now operating in a sensible and rational alliance. The workforce, alongside existing semi-official unions and labor activists, has shown solidarity in the face of any arrest or repression of members across any group or sector. Over the past few years, despite pressure, threats, arrests, convictions, and exiles, workers have stood firm on their goals, demands, and expectations, refusing to compromise. While certain factions seek to fragment worker unity through opportunistic and self-serving views, creating divisions between workers, activists, and unions, workers have awoken from this slumber thanks to their growing consciousness and the power of modern communication tools. They now possess a clearer historical understanding of their position and circumstances.

The result is a concrete, externalized understanding by workers of their situation and others, as well as their place in the system of production and the process of alienation.

In a philosophical sense, once workers become aware of their own existence, their inherent social value, and their position in relation to capital and capitalists—and once this awareness becomes widespread to the point of manifesting externally—they transform their own subjectivity, as Lukács puts it. When workers recall their own existence and compare their free time with the value derived from the product of their labor, or when they assess their own worth as human beings in relation to capital, they achieve awareness, and their consciousness deepens.

Workers seek to elevate their position in relation to capitalist forces, industrial owners, and the tools of production, even in opposition to governments and conciliatory workers’ representatives. They aim to take away the power of representation from those who misuse it. Thus, a sole focus on technological growth, developed industries, or adding restrictive laws and regulations—without addressing workers’ real demands or ensuring their livelihood—is a one-sided approach that will ultimately lead to the destruction and divergence of production and industry.

What Are Workers’ Demands?

It’s perhaps not far-fetched to say that the entirety of workers’ rights revolves around the right to independent unionization. The right to unionize, to organize politically, and to claim an identity is the fundamental right from which other rights—freedom of speech, protection from arrest and prosecution, political rights, the right to strike and protest peacefully—all stem and develop.

The state must not only legally recognize and validate the right of workers to unionize but also actively remove the barriers to strikes and protests. Creating false scenarios, prosecuting, fabricating charges, imprisoning and exiling labor activists, and disrupting their gatherings are difficult and oppressive responses to workers’ legitimate needs and demands.

Why do the government or the Supreme Labor Council feel entitled to impose slave-like wages that push millions of families toward ruin and exploitation?

Sustainable production and employment cannot be achieved through the means of meager wages and the slave-like living conditions of workers.

Women, too, are true and steadfast allies of the labor movement, and their voices of protest—given the specific challenges they face—are even more pronounced among female workers. Thus, the elimination of gender-based laws and anti-women regulations, as well as the eradication of gender discrimination in factories, have always been key demands of workers.

The movement of solidarity and support for workers has now extended to other sectors, promising a fundamental transformation. The distinguished record of the wage-earners’ and laborers’ movement has opened a specific social path, and the accumulated demands of the past few years have increased the expectation of policy changes. Yet hundreds and thousands of strikes and protests have remained unanswered. The labor protest movements, both civil and industrial, have even spread among official government employees.

The powerful strike movement of a vast number of workers for wages, against poverty, discrimination, and exploitation, in protest of the Supreme Labor Council’s decrees, and against wage repression and the empowerment of contractors and middlemen in the labor sector, remains alive. The low standard of living for workers, delayed wages, the erosion of housing rights, and the violation of the principles outlined in the Constitution have led to a kind of double oppression, marginalizing the poor and subjecting workers to extreme exploitation and violence.

The reality is that merely expressing demands through petitions and statements has not had much effect. Promoting and expanding strikes and protests, however, is a useful strategy for bargaining power and achieving change.

The goal of employers has always been to take away workers’ basic rights—such as freedom of speech, unionization, and political organizing—and to enact decrees that not only fail to protect these foundational rights but also perpetuate the status quo and hopeless conditions. Keeping up appearances and offering false hope to workers, sending legal or judicial representatives to negotiate on their behalf, are nothing but empty promises.

It seems, therefore, that there are unresolved issues in the country’s laws and its production and economic systems. Continuing the current situation will only lead to further exploitation of workers and deliver a fatal blow to production, employment, and investment. Providing an appropriate response to these conditions, amid rising inflation and soaring costs of goods and services, is an urgent necessity.

Tags

Discrimination Independent organization Labor strikes Mine explosion Miners Mustafa Ahmadian Paragraph peace line Peace Treaty 162 Tabas Mine Workers' rights Workers' union ماهنامه خط صلح