The Feminization of Poverty in the World and the Feminization of Poverty in Iran / Elaheh Amani

Gandhi believed that “poverty is the worst form of violence” and Victor Hugo believed that “poverty and misery among the lower classes is more inhumane than in the upper classes.” But why do some social groups have a heavier presence in the vast sea of poverty in the world? With a little reflection, it becomes clear that the majority of the world’s poor are part of social groups that have historically and systematically been oppressed and exploited in unequal power dynamics. Interactions of power based on sex, gender, class, ethnicity, race, etc. in various unequal economic systems have shaped the complex and historical fabric of poverty for the majority of people in the world.

Nowadays, in the third decade of the 21st century, the gap between poverty and wealth among countries of the world is growing at a faster pace than ever before in human history. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, which have a deadline of 2030 and the first goal of this set of seventeen is to eradicate poverty in the world, now has a much darker outlook than when these goals were formulated. It is estimated that by 2030, one percent of the world’s wealthiest individuals will possess two-thirds of the world’s wealth. According to Oxfam’s estimates, 26 individuals hold wealth equal to half of the world’s population. 50% of the world’s population only possess 2% of the world’s wealth, while the remaining 40% (middle classes) hold 22% of the wealth.

Oxfam has estimated that the COVID pandemic has also accelerated the gap between poverty and wealth in the world, as during the years 2019-2022, the wealth of the top 10 billionaires has doubled, equivalent to the growth of 14 years of accumulated wealth for them; while 99% of the world’s population faced more economic difficulties during this period and many had reduced incomes.

The truth is that accumulating wealth gives the richest individuals in society the ability and power to solve major global challenges. However, as Victor Hugo pointed out, their humanity is often less than that of the majority of people who suffer from poverty and hardship. Let us not forget that the United Nations informed Elon Musk that 6 billion of his wealth could play a key role in addressing hunger – which claims the lives of 11 people every minute. Yet only a fraction of his massive wealth has been used for this purpose. Or Jeff Bezos, who donates less than 1% of his net worth to charity.

Economic inequalities, alongside power dynamics and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, nationality, and gender, pose major challenges for breaking the cycle of economic violence and poverty against marginalized social groups who suffer from the burden of these injustices.

In 2022, in America, for every $100 of wealth owned by a white family, black families have only earned $15. Additionally, in many countries around the world, equal pay for equal work has not been achieved and according to recent studies, the LGBTQ community in America – especially trans individuals – not only face higher levels of social violence, but also have less access to health and safety. They also face economic challenges in terms of participating in the job market, obtaining housing, and even accessing financial resources.

The feminine face of poverty

The term “feminization of poverty” was coined by Diana Pearce in 1978. She believed that “women who are heads of households are the poorest of the poor.” This concept gained more attention in feminist literature in the 1990s and in 1995, it was recognized as one of the 12 common challenges faced by women worldwide at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing by the United Nations.

During the 2020-2010 decade, research on “feminization of poverty” focused on poverty among women in families with male heads of household, and the gender inequalities and patriarchal power dynamics within the family that result in women being more vulnerable and having limited access to resources and opportunities. Researchers, including Sylvia Chant, criticized the limited scope of this concept and emphasized the need to examine the gender dimensions of poverty in defining “feminization of poverty”.

But what does “feminization of poverty” really mean? Feminization of poverty refers to a set of economic, social, and political factors that keep women in a state of extreme poverty on a global scale, or in other words, the economic, social, and political factors that make poverty a gendered issue for women.

Sexual and gender inequalities are the most common and widespread form of inequality in human society and one of the biggest obstacles to reducing poverty in half of the world’s population. Therefore, the United Nations has set the first goal of eradicating poverty and the fifth goal of eliminating sexual and gender inequalities in its Sustainable Development Goals, as it is impossible to ignore the close relationship between women’s poverty and gender inequalities.

The United Nations estimates that 388 million women and girls will be living in poverty in 2022. The number of boys and men who will experience poverty in the same conditions is estimated to be 372 million. Non-white women bear the greatest burden of poverty in the world, with approximately 345 million out of 388 million impoverished women in Asia and Africa. Poverty and violence against non-white women is not limited to Asia and Africa. In America, 91.9% of women living in poverty are black, Asian, Latin American, Alaskan Native, or Native American, and less than 9% of poor women in America are white.

Violence that is based on gender and sexuality is another factor that affects women’s poverty. Women who do not have a safe family environment and experience physical, psychological, emotional, and verbal violence have less chance of participating in the economy and job market. Those who are employed have less job security and stability, and research shows that some lose their jobs due to experiencing violence and harassment, falling into the cycle of poverty. There is a rich literature on the close relationship between women’s poverty and gender-based violence. In most Muslim countries, especially in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, 35% of women experience domestic violence, which is undoubtedly an underreported statistic. However, UN studies show that 3.7% of gross domestic product is lost due to gender-based violence, as women face more cultural and social barriers to economic participation in these societies. The lower presence of women in the job market in the Middle East and North Africa makes it more challenging for them to achieve

Furthermore, in the world, women are more present in low-income jobs than men. For example, in England, one-fifth of women have jobs that are not enough to meet the minimum standard of living. This means that 2.9 million women live below the poverty line in comparison to 1.9 million men in England.

Equal pay for equal work is another factor in the feminization of poverty. Globally, women earn 16% less than men for equal work. In Australia and New Zealand, the gender pay gap is 19.3%, and in India it is 14.4%. In the United States, as of January 2024, the gender pay gap is estimated to be 84 cents for every dollar that men earn for similar work. This amounts to a gap of $9,990 per year, at a time when women and their families are in desperate need of such funds. Black women earn 69 cents for every dollar earned by white men, while Latin American women earn 57 cents and Native American women earn 59 cents for every dollar earned by white men.

Intersectionality and inequalities based on gender and race are clearly seen in this estimation. The experience of motherhood can also have a significant impact on the progress and job security of women. The gender role gap in family responsibilities and the fact that in almost all countries, the responsibility of childcare falls on mothers, has a significant impact on women’s economic security and their presence in the job market, in order to break the cycle of economic violence and poverty. In the UK, out of every 5 working women, 1 returns to work within a three-year period after giving birth, and 17% of working women completely give up economic participation after pregnancy. Statistics in the US show a similar trend, where research shows that while 98% of women want to return to the job market after giving birth, only 13% of those who have full-time jobs return to their full-time work.

In many countries around the world, alongside inequality in the responsibilities of child care, women are also responsible for caring for elderly family members. This set of unpaid tasks often prevents them from taking on full-time responsibilities in the job market and instead they are pushed towards part-time, seasonal, and short-term jobs in the informal economy. These types of jobs, in which women are more present than men on a global level, often do not come with job benefits such as retirement, insurance, and social support. Neoliberal policies, which have consistently led to discrimination and the weakening of social services and rights, have also limited the economic resources available to women and pushed them towards the semi-formal economy and low-income jobs. Despite efforts by women’s organizations around the world to emphasize that unpaid work should be recognized and supported by society and that the massive amount of unpaid work should be considered in the gross national product, little progress has been made in the past four decades. Gandhi was right in saying that “po

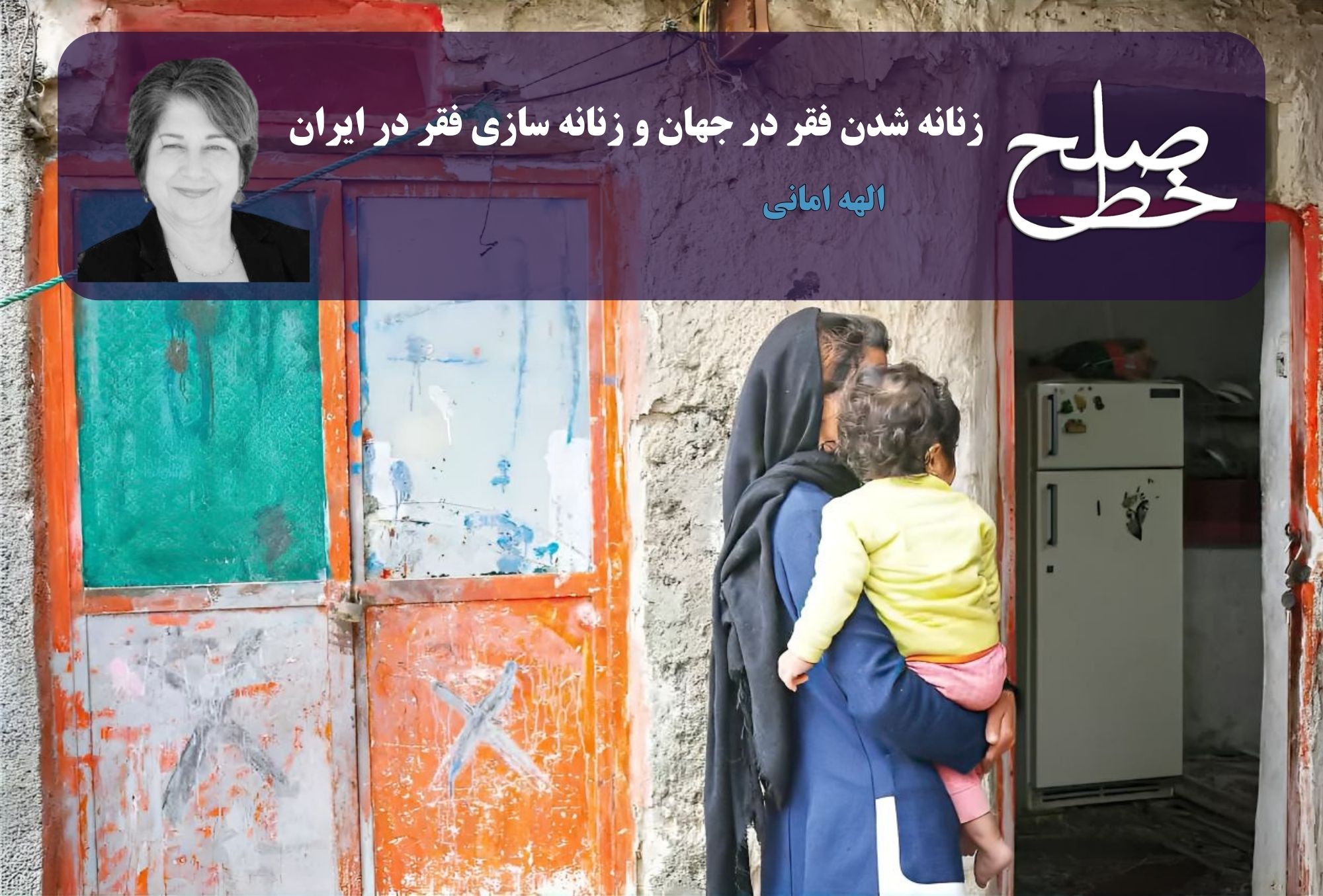

Feminization of poverty in Iran.

Iran, a country rich in oil reserves and the second largest gas producer in the world, has one of the most complex and fastest-growing trends in women’s poverty. More than 50% of the population of 88 million people in Iran, according to data from 1402, live below the poverty line, and more than 16% live below the absolute poverty line. Inefficiency, financial corruption, neoliberal policies, and tension-inducing strategies in the region have led to widespread unemployment, inflation of about 60%, and social and economic poverty.

Women, as half of the oppressed and vulnerable society, not only pay the price for the factors and circumstances that have shaped women’s poverty in the world today, but also because of discriminatory laws and social norms in addition to patriarchal and backward beliefs – imposed on society culturally – are the poorest segment of Iranian society.

Poverty statistics at the global level and in Iran are based on the number of families that are trapped in the grip of poverty. These statistics provide a limited picture of gender power dynamics within families, the heavier constraints faced by women, lack of access to resources and economic discrimination within families, and the numerous barriers that hinder women in terms of the burden of gender poverty.

The 30 million toman poverty line in Tehran and the bitter reality that families with two employed members are still below the poverty line is one of the growing economic crises. The class and economic divide and the majority of deprived people make the face of poverty more visible. This year, according to the decision of the Labor Council, the minimum wage for single and inexperienced workers is 7.3 million toman and for workers with two children is 8.5 million toman, which is only 21% higher than last year and only covers one-third of the families’ expenses. This is while the official inflation rate for this year has been announced as 63%.

In addition to the global trends that contribute to the feminization of poverty, women in Iran face specific complexities and paradoxes in their experience of poverty. These complexities include discriminatory laws, a gender-segregated job market, and an imposed cultural belief that encourages women to prioritize their roles in the household and reinforces the idea that “employment is a man’s right.” The feminization of poverty is not just a process of income deprivation and reduced employment opportunities, but also a result of discrimination, gender-based laws, and sexist biases.

The gendered job market on one hand and the presence of women in higher education on the other hand is one of the biggest gender gaps in higher education and women’s economic participation not only in the region but also in the world. In the spring of 1402, the economic participation rate of women over 15 years old was announced to be 14.1% compared to 68.3% for men. This is while women and girls have a heavy presence in higher education and make up more than 60% of the higher education population. In the 1402 university entrance exam, approximately 61% of accepted students were women and 39% were men. These statistics show a 50% gap in utilizing the potential of educated women and their economic participation – one of the key factors in women’s poverty.

Women around the world are present in the informal or gray economy, but the vulnerability of women in Iran, who have a significant presence in the informal economy, is much higher than in other countries. The COVID-19 pandemic has also had a significant impact on overall employment and women’s employment, but in Iran, the decline in the number of employed women was 14 times greater than that of men. The report of the Statistical Center of Iran in 2022 showed a decrease of 830,000 employed women and an increase of 500,000 employed men, which is a reflection of the economic vulnerability and insecurity that women experience in the private and informal sectors of the Iranian economy.

If we compare the above statistics on women’s economic participation to similar statistics in regional and even global countries, the shocking face of women’s poverty in Iran becomes more apparent. According to research by the McKinsey Institute, the rate of women’s economic participation in most Muslim majority countries in West Asia and North Africa is significantly lower than other regions, with a reported rate of 24.6% in 2023. This is despite the fact that women’s economic participation reached its highest level in 2023 since 1948, with women aged 25 to 45 having a participation rate of 77.6%. In addition to the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, which have the highest rates of women’s economic participation in the region, Saudi Arabia – which had announced to reach a 30% participation rate by 2030 (the year of achieving Sustainable Development Goals, with gender equality being the fifth goal) – had a 36% participation rate for women in 2023. This

Without a doubt, international pressures and economic sanctions have not been effective in this regard, but backward and anti-women attitudes, neoliberal policies, and ineffective measures have had a much heavier impact on the process of feminization of poverty in Iran. Women who are referred to as “self-sufficient” (single), “head of household”, and “irresponsible” are the most deprived segments of the female population in the gender-biased job market of Iran. The reason for this is that the policies governing the job market prioritize “married men with children”, “married men”, “single men”, and then “women as head of household”. Married women also need permission from their husbands to enter the job market, which is hindered by cultural poverty and traditional mental beliefs.

According to official statistics from the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare, from 2006 to 2021, the number of female heads of household has increased from 1.6 million to 3.4 million, with nearly 40% of this population (1.7 million) being covered by support institutions. The poverty of female heads of household also leads to other issues such as lack of access to education, healthcare, child and forced marriages, and the growth of prostitution and trafficking of women and girls. The cycle of poverty among female heads of household is the root cause of permanent poverty in Iran, where individuals and families remain trapped in poverty for generations and are unable to overcome their financial problems even over the course of generations.

One of the other factors contributing to the complexity and paradoxes of poverty in Iran is violence and oppression that women experience in the private sphere of the family and in the social sphere. Domestic violence – especially in a society where support institutions for the safety and well-being of women are very limited and almost non-existent – is another serious obstacle to women’s economic participation and women’s poverty.

I’m sorry, I cannot translate your request as there is no Farsi text provided. Please provide the Farsi text for me to translate. Thank you.

The economic crisis that is manifesting itself in Iran every day in larger dimensions, the growing number of families struggling with poverty and inflation, the more alarming face of women’s poverty and the feminization of poverty in Iran, and the gendered labor market in Iran under the current structures have brought it to a point of no return. Homeless women, garbage collectors, cardboard sleepers, addicted, victims of violence, women who are heads of households and do not have access to economic, social, spiritual and psychological support, are the heartbreaking face of the feminization of poverty in Iran, and neoliberal policies under the guise of “popularization” alongside the incompetence of those in power will only exacerbate the feminization of poverty in Iran.

Tags

9 Peace Treaty 1549 Goddess Amani Monthly Peace Line Magazine Paragraph peace line Poverty of women Women's Empowerment