The story testifies / Alireza Ismailzadeh

Literature has recorded the first execution to the last massacre.

You must have heard this sentence many times: “Their work is finished.” From the mouth of a taxi driver, a working woman, a daily wage laborer, or a student who has confidently set a deadline: “They won’t see the end of 1401,” “Next year in Aban,” “Soon,” or even when you say it yourself, involuntarily to a stranger on the street: “The invaders will leave this land.” The shortening of the time gap between nationwide protests in Iran from 1388 to 1401 and the recent protests being called a “revolution” by the protesters themselves is a clear indication that these sentences have become a public demand today. The increasing demands of different segments of society on one hand and the constant suppression and imposition of various forms of oppression (class oppression, gender oppression, ethnic oppression, religious oppression, etc.) on Iranian citizens by the government on the other hand are the main reasons for the people of this geography to be in

In this note, we will discuss some of the most prominent oppressions in the past forty years through reviewing some of these stories.

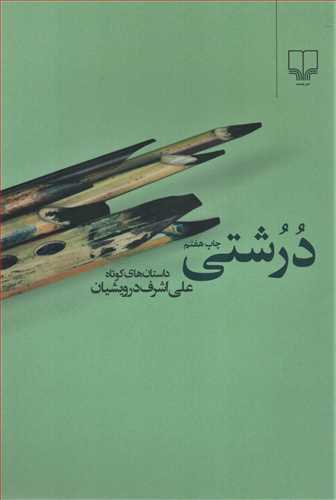

“Size”

Ali Ashraf Darvishian and the Suppression of Kurdistan.

The conquerors, wherever they went, brought flowing water, but the destroyers brought a river of blood. He was one of the destroyers. In every corner of Tehran, he spilled blood; from the “Rafah” school to Shahr-e-No. He poured blood on every land he saw; from Shiraz to Kermanshah, from Khorramabad to Ahvaz, from Gonbad Kavus to Sanandaj. A potential threat that the 1957 revolution made into a reality. He used to say: “My revenge is not for myself; I will take it for others, for the oppressed, for the helpless, for the innocent.”

He, who was the ruler of the law, takes photography with him on his fifth journey to Kurdistan in the month of Shahrivar in 1358 (1979) to document what he intends to do; with a clear conscience and pride in his crimes, with a smile towards the camera, over the corpses stained with lead…

A few days later, a photo from that day will be published in Ettelaat newspaper; a photo without the photographer’s name, which will be printed on the front page of the world’s most reputable media a few days after its publication in Iran; with the title: “A Fire Squad.”

Coarseness.

Ali Ashraf Darvishian’s narrative is “The Fire Brigade”.

Coarseness.

It begins on a rainy and scary day; in a space where “the sky was dark and stormy”. The story is narrated through the eyes of a child, and who is more vulnerable than children to describe fear?

The child is busy cutting reeds to make a thick pen in a corner of the swamp. From a hole in one of the cut reeds, he looks beyond the swamp and sees what is taking shape in the murky space, which is actually the same image that Jahangir Razmi captured from the rain of arrows; “a group of fire” that was dramatized in the minds of the impoverished: “Three dusty jeeps were standing there and people were disembarking with black rains…”

The black-clad ones, with their checkered faces, disembarked eight people from the jeeps. Their eyes were covered with white strips and behind the pouring rain, which was pouring madly, they quickly lined everyone up. The first person on the right was tied up and blood was dripping from under the bandage….

The crystal rods of the chandelier make the rain tremble.

The pressure and impact of the bullets threw the third and fourth person, who were young, thin, and frail, into the air for a moment…

As the black cloaks pass by, “Khaleh Siavakhsh” appears. He sets fire and sits with the young boy. Khaleh, unaware of what has happened, is busy making a flute with reeds stained with blood. When he finishes his work, the boy hears a strange melody from the other side of the reeds: “Play the flute, play the flute/ How beautifully you play the flute/ Play in the alley and in the market/ They killed me in the reeds.” The dervishes, with the sound of the flute and the terrified mind of the boy, give him back his life, once again showered with arrows.

“Mirage is infidel.”

The breeze of the dusty and the prisons of the sixties.

“Torture must hurt the skin, pass through the flesh, and break the bones.” These words were spoken by Mohammad Mohammadi Gilani, the religious ruler and head of revolutionary courts, in an interview with Kayhan newspaper on September 28, 1981, regarding the method of flogging prisoners.

“Miraei is an infidel.”

“It begins like this: ‘Suddenly, I felt like a dog. Not a literal animal, no! On the contrary, a submissive and unfortunate creature.'” A sudden and shocking start that has more similarities to the end of a story than its beginning. That is why the story, instead of moving forward, constantly escapes to the past to explain the transformation of the narrator into a dog; not so distant past in the same place: a prison.”

Nasim Khaksaar knows that the formation of animals in her story is a victim of the policy of rehabilitation in the prisons of the 1960s. A disabled human, who gives up his past for escape and liberation from prolonged torture, denies his past and ends up seeking refuge in the arms of the torturer: “My real father is Haji Agha.” Who doesn’t know that Asadollah Lajvardi, the head of Evin Prison in the early 1960s, liked to be called “Haji Agha” by the prisoners.

In the story of “Khaksaar”, among all the tortures used during the stages of repentance, the focus is on “whipping”; a deadly torture that according to Mohammad Gilani should make the skin hurt: “Who should I tell the truth to; it wasn’t me. It was my body. Oh, my skin, it was my skin. Then Haj Agha arrived like angels. With my free hands, I held onto his knees and begged: Haj Agha; don’t leave me alone.” Haj Agha was there to accept the repentance of a prisoner and cover his naked and skinless body with animal skin.

If before the revolution of fifty-seven, we were faced with dualities such as prisoner-guard, tortured-torturer, detainee-interrogator inside prisons, after this event, another element is added to these dualities and sits between them; the phenomenon of the new arrivals that grows mostly in the prisons of the sixties: repentance…

Repentance is the third element that was added to the prisons of the 1960s. He is both a prisoner and a guard, a detainee and an interrogator, a victim and a torturer. He can sleep in the same cell as his former comrades and betray them. He, who was once under the executioner’s sword, is now an empty being devoid of emotions, shooting the salvation arrow at those who have resisted wearing the animal skin too much.

»

“Spirits are bodies.”

“Shahriar Mandanipour and Executions of 1967.”

Choosing a perspective for writers who want to narrate a crime in their story is one of the most difficult parts of storytelling, especially if the crime goes beyond the individual’s personal sphere of action. Often, writers do not use omniscient knowledge in such situations for two main reasons: firstly, because the inability to describe the victim’s inner thoughts and feelings leads to less empathy from the audience, and secondly, because the unreliable narrator is contrary to the characters who are always honest. This is why in such stories, we are mostly faced with a first-person perspective, and it is the victim who describes the events.

There are crimes in history that, although they occurred at a specific time, their tragic consequences continue for years and decades, constantly adding to the number of victims. The massacre of political prisoners in the summer of 1967 is one of these crimes. Shahriar Mandanipour was involved in these crimes.

“Spirits and bodies.”

It refers to this crime and one of its subsequent victims.

“Spirits and bodies.”

It is shining. A pioneering short story that demands a place for reconstruction. If writers in the stories written in the early years after the 1960s, become the narrators of prison spaces and the executions of prisoners, and lament for the East and other mass graves, Mendonipour in…

“Spirits and bodies.”

She has abandoned crying, taken the criminal as a target and attacks towards him. She no longer goes to the cemetery or writes a description of the families, but cleverly enters the criminal’s house and disturbs his life.

The story narrates the fear and anxiety of an interrogator – one of those torturers who in the summer of 67 would hang the noose around the necks of the condemned. But the narrator is not a killer, it is his wife; a religious woman who witnesses the entry of unfamiliar objects into their home; objects that terrify the man; objects that are released from the fists of the condemned when they gasp for air; fragments of a shell, a sprouting potato, a pine cone, a child’s quince, a crow’s feather, a piece of fabric, and so on. Objects that serve as a warning: we have been summoned, be afraid for you will never be safe.

«

«

It was autumn.

“Mohammad Rahim, brotherhood and the killings of chains.”

“We, as writers, express and publish our feelings, imagination, thoughts, and research in various forms. It is our natural, social, and civil right for our writings – whether it be poetry or fiction, plays or screenplays, research or criticism, and also translations of other writers’ works from around the world – to reach our audience freely and without any obstacles. Creating barriers to the publication of these works, for any reason, is not within the jurisdiction of anyone or any institution.”

Their main goal in signing and registering their names at the bottom of this paragraph was, as they wrote, “to remove the obstacles to freedom of thought, expression, and publication.” However, they were a barrier to the oppressive regime; writers who had the courage to speak out and deny. Shortly after this outcry, which became famous as the “Statement of One Hundred and Four Writers”, security forces began a new project of removing obstacles; projects whose start date we do not know, but the first victim among the signatories of the aforementioned statement was Ahmad Miralai, on November 2, 1995.

Mohammad Rahim’s Brotherhood in the Short Story.

It was autumn.

It has narrated that day…

The story is divided into two parts. The first part seems to be a true account of the news of the disappearance and subsequent murder of Mir Aalaei, and his brother’s presence in the forensic medicine department. The second part is the story written by the narrator – who is actually Mohammad Reza Aalaei – from the time of Ahmad’s departure from home to the moment of his murder. In the first part, there are many witnesses; from Aalaei himself to acquaintances who had connections with Mir Aalaei, they narrate what happened before the murder and ultimately on his body.

From the threats: “One of the interrogators who had asked why I had signed the open letter protesting the imprisonment of Saeedi Sirjani, said: ‘This is my professional duty. I will continue to fulfill this duty from now on’.”

Since the time when “nothing had yet fallen as the murders of the chain of tongues” …

From seeing the injection spot on the left arm: “But the injection spot couldn’t be forgotten.”

Part Two (Description of the Writer’s Murder) But there is no witness. It is the narrator who, through the same injection site on his arm and with the help of his imagination, writes a story about the kidnapping and killing of Mirali. From 7:30 am on November 2, 1995 until some time later; the moment the syringe fell into his left hand..

«

Empty benches.

Hossein NoshAzar and suppression of the November 98 protests.

The Islamic Republic, in its forty-four years of existence, has never been oblivious to oppression and violation of human rights, and has been busy collecting a complete collection of crimes, similar to professional collectors. Among all the inhumane actions committed by the rulers of this land, perhaps the most despicable is their treatment of children. The use of children for military purposes, deprivation of education for various reasons, and alarming statistics of child labor, among others, show that in the government of the Islamic Republic, even the most backward and inhumane laws have not lost their function for children. The arrest and execution of Mona Mahmoudnejad at the age of sixteen and her execution at the age of seventeen for being a Baha’i in the early 1990s is a clear example of this claim.

Since the beginning of the 1957 revolution until now, the suppression and direct killing of children has been carried out through methods such as execution in prison and continuous street massacres. However, the extent of these crimes has reached a point where even the rulers cannot deny them, as seen in two historical periods: the mass execution of political prisoners in the summer of 1967 and the suppression and killing of protesters in November 1998.

As far as we know, during the nationwide protests of November 1998, at least twenty-two children under the age of eighteen (twenty-one boys and one girl) were killed by military-security forces(1) and hundreds of other children were arrested and tortured throughout Iran. Hossein Nushazar in the story.

Empty benches.

The narrator becomes a child in November.

The story begins in a school, continues on the street, and ends in homes that are no longer safe. It is told from the perspective of a teacher who is also the father of “three girls on the verge of maturity.” In the school, the teacher is faced with an empty seat of a student, on the street he witnesses the murder of a fourteen or fifteen-year-old child, and at home he is afraid for his daughters. The story revolves around loss; the story of a child killed during the November 1998 protests in the city of Shahriar. Nushazar summons the past with a description of the empty seat of the killed child at the beginning of the story, then continues with the present by describing the moment of another child’s death on the street, and finally, by depicting the narrator’s fear for the future of his children, he warns of the dark and dead future of all the children of this land.

Note:

1- The information of 324 identified casualties of the November 2019 protests.

International forgiveness.

November 25, 2021.

Tags

7 Peace Treaty 1397 Ali Ashraf Darvishian Alireza Ismailzadeh Chain killings coarseness East Empty benches Executions of the 1960s Hossein Azarnoush It was autumn. Mahsa Amini Mohammad Reza Akhavat Nationwide protests November 98 Shahyar Modnipoor Spirits and bodies Woman, freedom of life