The National Women’s Health Document and the Erasure of the Discourse on Violence/ Pardis Parsa

Recently, the “National Women’s Health Document” was issued by the President of the Islamic Republic and the head of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, with stated goals such as promoting women’s physical, mental, social, and spiritual health. Yet rather than being the result of engagement with the lived realities of women, the document appears to stem from a selective and ideological framing of the concept of health, turning the female body—due to its reproductive capacity—into a site of power and policymaking. At the same time, the critical issue of “violence against women,” one of the most serious threats to women’s physical and mental health, has been sidelined in the document. Its fate has been tied to a separate, stalled bill that remains entangled in bureaucracy and deep political disputes.

The Biopolitics of the Female Body

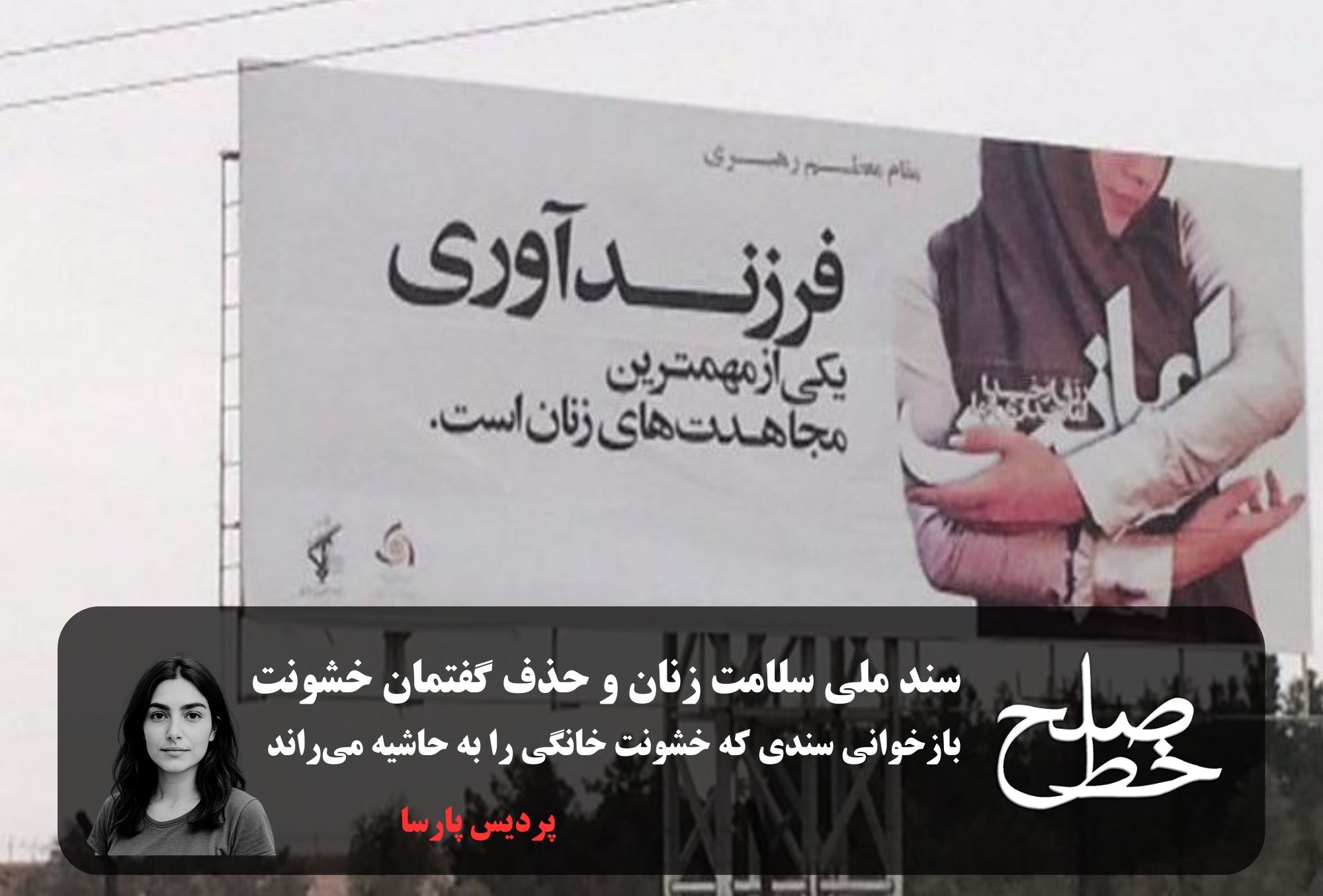

Population policies in post-revolutionary Iran provide a classic example of Michel Foucault’s concept of “biopolitics,” in which the population, as a biological entity, is subjected to the state’s surveillance and discipline. While in the 1990s population control policies were pursued with the aim of economic development, from the 2010s onward, with a shift in official discourse, the female body became a battlefield of power in the struggle against “population aging.” In this context, the National Women’s Health Document is not a health document but a security instrument designed to guarantee reproduction and preserve the traditional family structure.

Through medical and cultural systems, the state seeks to transform women into “disciplined subjects” whose primary duty is childbearing. Within this framework, any activity that strengthens women’s autonomy over their bodies—such as access to contraception or the right to safe abortion—is portrayed as a threat to national security.

This biopolitical management has manifested most clearly in the “Law on the Protection of the Family and the Youthful Population,” which has imposed severe restrictions on access to healthcare services. The elimination of free distribution of contraceptives and the increased difficulty of medical screenings indicate that the state is willing to disregard women’s health risks in pursuit of the overarching goal of population growth. Women’s health has thus been reduced to “reproductive health,” while their psychological and social dimensions are overshadowed by considerations of regime expediency.

For this reason, the state avoids seriously addressing the issue of violence against women, as doing so would require recognizing women’s “agency” and their “right over their own bodies.” If the government were to acknowledge women’s right to resist forms of violence such as child marriage or forced pregnancy, total control over their reproductive capacity would be disrupted.

Spirituality Instead of Justice

The National Women’s Health Document defines health across four dimensions: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. However, an analysis of these dimensions shows that the further one moves toward “meaning,” the more women’s suffering becomes abstracted and stripped of its material and political contexts. In the realm of mental health, rather than focusing on trauma resulting from domestic violence—identified in numerous studies as one of the most significant causes of depression and anxiety among women—emphasis is placed on general concepts such as “vitality,” “social hope,” and “strengthening the foundation of the family.”

The most critical aspect of this definition is the prominence given to spiritual health. In official documents, spiritual health often becomes a tool for encouraging women to adapt to unjust conditions. A woman subjected to chronic violence is called upon to exercise patience, spiritual elevation, and modest living, without any guarantee of her physical or legal security. Within this logic, suffering is viewed not as a sign of injustice but as a moral test. By excluding concepts such as marital rape from the sphere of sexual health, this approach effectively legitimizes and renders violence invisible.

The Deadlock of the Women’s Security Bill

One of the main reasons for the absence of the issue of violence in the Women’s Health Document lies in the prolonged and uncertain status of the bill that was meant to provide its legal foundation. The “Bill on Combating Violence Against Women,” drafted in the early 2010s, underwent substantive changes as it passed through various institutions. Even its title was altered to “Preserving the Dignity and Supporting Women and the Family” in order to remove the word “violence.” This political resistance stems from fear that explicitly addressing violence would weaken the traditional authority of men within the family, which is regarded as the core of political stability.

Iran’s legal structure—based on Article 1102 of the Civil Code, which designates the husband as the head of the family and in some instances grants him the right to discipline—constitutes the greatest obstacle to the explicit criminalization of domestic violence. Instead of challenging these barriers, the National Women’s Health Document, by emphasizing a “balance of rights and duties,” effectively endorses this unequal structure. Women’s rights activists argue that without adherence to global health standards and without the adoption of firm protective laws, any document in the field of women’s health will amount to a merely advisory and ineffective text.

Dissecting the Removal of the Word “Violence”

The removal of the word “violence” from the National Women’s Health Document and its replacement with terms such as “misconduct” in related bills constitutes a political strategy to erase the problem. From the perspective of the sociology of language, words carry legal weight and assign responsibility. The term “violence” denotes a structural phenomenon and a crime that obliges the state to intervene. In contrast, “misconduct” reduces the issue to individual or familial misbehavior. This change in terminology is an attempt to absolve the state of accountability for women’s physical security.

The sociological reason behind this omission lies in the fear of shattering the idealized image of the “sacred family” in official discourse. Acknowledging the existence of “structural violence” would amount to admitting the failure of the state’s cultural and educational policies.

The legal consequences of this linguistic shift are profound. When a judge or judicial officer encounters the term “misconduct,” their approach is steered away from deterrence and punishment toward reconciliation—often meaning the return of the victimized woman to her abuser. This manipulation of language effectively strips the law of its protective identity and reduces it to a symbolic text crafted to preserve political appearances. The removal of the word “woman” from titles such as human trafficking or acid attacks in recent years is part of the same systematic trend of concealing the gendered dimensions of crimes in Iran.

Weakening Support Structures

According to global statistics, nearly one-third of women in Iran experience violence from their intimate partners. Each year, more than 74,000 women seek forensic medical examinations related to spousal abuse, while estimates suggest that the actual number may be nearly 100 times higher. Reports also indicate a rising trend in femicide: between June 2021 (Khordad 1400) and June 2023 (Khordad 1402), at least 165 cases were recorded in the media—an average of one woman killed every four days. According to the latest reports, since the beginning of 2025 (1404), 63 cases of femicide have been documented. These alarming figures underscore the urgent need for strong support structures.

Meanwhile, “safe houses,” the primary shelters for women experiencing violence, face severe capacity shortages. Currently, only 31 safe houses exist across Iran, each with a capacity of twenty to twenty-five individuals. In a megacity such as Tehran, only three safe houses have been reported. Moreover, the State Welfare Organization has pursued a policy of transferring these centers to the private sector without providing adequate financial support. As a result, non-governmental centers face severe financial difficulties and security pressures, while the Welfare Organization’s attention to them has nearly diminished to zero. Official policy often prioritizes returning women to their families—even in high-risk situations—and focuses on “restoring calm” rather than protecting women.

This pattern is evident in other structures as well. “Social Emergency” (hotline 123), despite handling a high volume of calls—approximately 30 percent of which relate to domestic violence—suffers from budget shortages, lack of specialized personnel, insufficient vehicles and infrastructure, and the absence of legal authority for social workers, all of which severely limit its effectiveness. In many cases, social workers lack permission to enter homes and therefore lack the power to intervene.

Government budgeting further reflects evasion of financial responsibility in this domain. For instance, the provision allocating “one percent of institutional budgets to women’s affairs,” which could have provided sustainable funding for support programs, was merged into other cultural and ideological budget lines and effectively lost its function.

This evasion of financial and executive responsibility occurs while the budgets of propaganda and ideological institutions have experienced remarkable growth—such as a 975 percent increase in the budget of the Islamic Propaganda Organization. This budgetary gap sends a clear message: the state is willing to spend heavily to promote a particular lifestyle, yet it allocates no resources to protect women’s lives against the very patriarchal structures embedded in that lifestyle.

Confrontation with International Norms

The National Women’s Health Document reflects the state’s confrontation with global health and human rights standards. Members of Parliament and the document’s drafters argue that addressing violence against women reflects feminist perspectives and international frameworks that conflict with indigenous values. In doing so, the state draws clear boundaries against documents such as the 2030 Agenda and human rights conventions like the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women” (CEDAW), labeling any demand for women’s security as “cultural infiltration.”

Consequently, instead of adopting scientific and global definitions of mental health and social well-being, the National Women’s Health Document employs ambiguous terms such as “Sharia-based spiritual health.” This ideological definition paves the way for overlooking legally sanctioned forms of violence—such as compulsory obedience, child marriage, marital rape, or the right to discipline—since these are not regarded as violence within traditional interpretations.

This approach has led to the removal of concepts such as “gender justice” and their replacement with “justice based on innate differences.” From the perspective of the drafters, gender equality is a Western concept that leads to immorality and the collapse of the family. Within this worldview, legally sanctioned violence is not only not seen as violence but is considered part of the natural order of the family. In such a framework, a woman’s health is defined as her adaptation to this patriarchal order.

When the state refuses to join international treaties and even avoids using the word “violence,” it effectively shields itself from international oversight and human rights pressure. As a result, Iranian women are left alone in the face of structural violence, their voices drowned out by slogans of “maternal dignity.”

The issuance of the National Women’s Health Document marks a new chapter in the confrontation between the “ruling biopolitics” and the “lifeworld of Iranian women.” Despite all its claims, the document displays selective blindness toward the lived realities of Iranian women’s suffering. The absence of domestic violence from official definitions of health is a deliberate political choice aimed at preserving traditional structures of power within the family. As long as violence against women is not recognized as a public health crisis and policymaking is not redefined on the basis of individual security and human rights, women’s health in Iran will remain fragile and unequal. Correcting this course requires moving beyond an instrumental view of women and enacting firm protective laws that no longer regard the four walls of the home as a space for the unchallenged exercise of male authority. Health is a right that must not be sacrificed at the altar of political and ideological expediency.

Tags

Childbearing Domestic violence Michel Foucault National Women's Health Document peace line Peace Line 178 Violence Violence against women Women's body ماهنامه خط صلح