Education Trapped in a Triangle of Inequality/ Reza Herisi

In the official discourse of development, the educational system is consistently portrayed as the engine of social mobility and the embodiment of meritocracy. Ideally, this modern institution is tasked with fostering talent by providing equal opportunities regardless of class, ethnicity, or geographic origin, thereby enabling a fair distribution of societal positions. However, accumulated evidence in Iranian society—from macro-level data to lived experiences—paints a different and troubling picture: a deep rift exists between this “promise” and “reality.” Rather than serving as a ladder of advancement for the lower classes, the education system has become an effective tool for reproducing and legitimizing the privileges of the upper classes. This begs the crucial question: through what structural, institutional, and economic mechanisms has Iran’s educational system undergone such a reversal of function? In other words, how and why have schools—originally envisioned as arenas of merit-based competition—turned into spaces where inherited and class-based privileges are entrenched? The answer lies in dissecting a “triangle of inequality,” which we will explore in the following sections.

To grasp the depth of the current crisis, it is necessary to trace the genealogy of the logic of class-based education in Iran. Historically, Iranian society has always exhibited a hierarchical structure, and education, as a result, has served as a tool for differentiation and the preservation of those hierarchies. In the relatively recent past, during the Sassanid era, society was strictly divided into four closed classes, and higher education—especially in bureaucratic and religious fields—was exclusively reserved for the ruling classes (nobles and Mobeds). (1) This rigid structure blocked any possibility of social mobility through knowledge. With the advent of Islam, although its egalitarian ideology could have challenged these structures, the pre-existing class logic was reconstituted in new form. The formal class system was replaced by the dichotomy of khawas (elites) and avam (commoners), and land ownership became the principal axis of inequality. (2) New educational institutions, such as the Nizamiyya schools, while seemingly inclusive, in practice limited access and the ability to pursue full-time study to those from economically and socially privileged families. These institutions mainly reproduced bureaucratic and religious elites and never evolved into universal mechanisms for educating the general populace. (3)

The paradox of “centralized modernization” during the Pahlavi era took this logic to a new level. The concept of “universal education” became a pillar of modern nation-state building, but its implementation was heavily imbalanced. The best schools, teachers, and resources were concentrated in the capital and major cities, creating a structural divide between the center and the periphery—a divide that persists to this day. (4) Simultaneously, the emergence of elite private schools and the trend of sending children of affluent families abroad sowed the seeds of modern educational inequality. During this period, education acquired a dual function: on the one hand, it offered limited pathways for upward mobility to the urban middle class, and on the other, it remained a powerful mechanism for reproducing the privileges of both traditional and emerging elites. (5) This historical background reveals that class-based education in Iran is not a recent phenomenon but the continuation and restructuring of a longstanding historical logic, reproduced over time in accordance with changing economic and political structures.

After the 1979 Revolution, and despite the official discourse’s emphasis on justice, the mechanisms of educational inequality were not dismantled. Instead, over the past decades—particularly under the influence of economic adjustment policies—they have become more complex and effective. Today, this inequality operates through three interlinked mechanisms that form what we call the “triangle of inequality”:

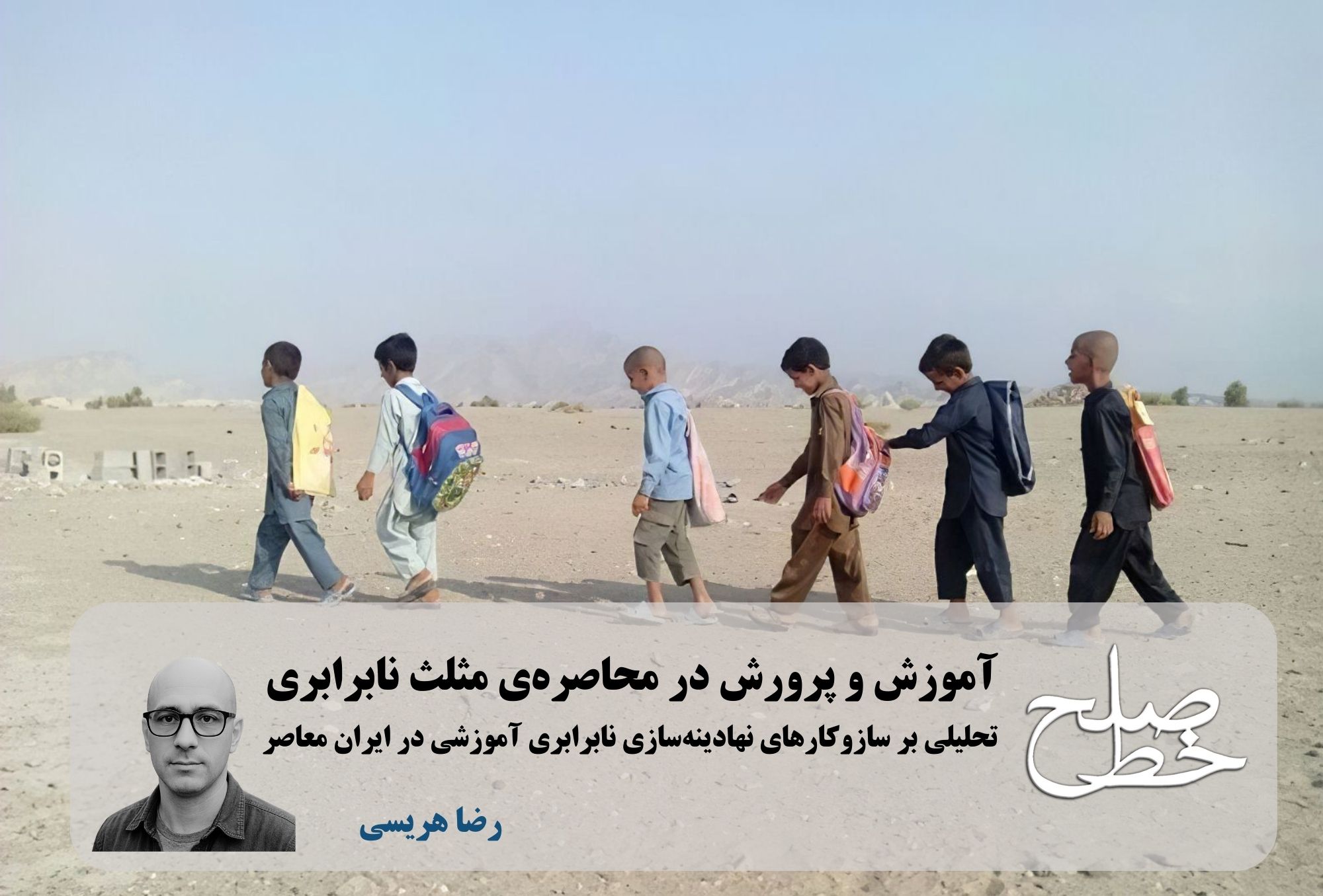

First Side: Structural Center-Periphery Divide and the Geography of Inequality

The first and most deep-rooted dimension of inequality lies in the uneven distribution of educational resources across the country. This historical gap is now traceable through tangible quantitative indicators. According to official statistics, the national average of educational space per student is about 5.2 square meters, yet this average masks a highly unequal reality. For instance, in a relatively well-off province like Yazd, the figure exceeds 7.5 square meters, whereas in the underprivileged province of Sistan and Baluchestan, it drops to only 3 square meters. (6) This inequality extends beyond physical infrastructure to include disparities in equipment quality, access to technology, and, most critically, the distribution of qualified teachers. Reports by the Parliament’s Research Center repeatedly show that many provinces suffer from severe shortages of specialized educators. (7) The consequences are devastating, leading to the highest dropout rates and numbers of out-of-school children in the country—figures consistently associated with Sistan and Baluchestan. (8) These statistics highlight that for an Iranian child, their “geography of birth” has become the most decisive variable in determining access to quality education—the first link in the chain of reproduced deprivation.

Second Side: Commodification and the Parallel Education Industry

Alongside the ongoing regional divide, the state’s retreat from its public service obligations has turned education into a commodity. The gradual erosion of the authority and quality of public schools has created a vacuum rapidly filled by a colossal “parallel education industry,” commonly known today as the “entrance exam mafia.” With a market turnover exceeding 70 trillion tomans, (9) this industry thrives on the belief that public education alone is insufficient for success in the entrance exam marathon. Exam prep classes run by self-styled “educational gurus,” mock tests, supplementary textbooks, and private tutoring have turned education from a public right into an expensive luxury. This process has transformed educational competition into a high-stakes contest based on economic capital, where victory is determined not by inherent talent but by a family’s financial means.

Third Side: Institutionalized Educational Segregation

If geographic inequality and commodification represent the two external sides of the triangle, the internal and completing side is the mechanism of segregation, implemented by the state itself through the creation of special schools (e.g., gifted, exemplary, and semi-private schools). Although initially established to identify and support exceptional talent, these schools have become central tools for reproducing class privilege. By attracting more capable students—who typically come from families with higher cultural and economic capital and represent less than 3% of the entire student population—and by allocating the best teachers and resources to these institutions, they have systematically drained regular public schools of their qualitative assets and institutionalized educational inequality. In the 2023 (1402) national entrance exam, over 80% of the top 3,000 ranks belonged to students from SAMPAD, exemplary, and elite private schools, while ordinary public schools—despite serving the majority of students—accounted for a negligible share. (10)

These special schools have become “exclusive clubs,” where entry depends less on innate talent and more on long-term family investments in the ancillary education market. Analyses of the 2024 and 2025 (1403 and 1404) entrance exams confirmed the effectiveness of this “triangle of inequality.” Official data shows that the combined share of SAMPAD and elite private schools in top ranks surpassed 95%, while ordinary public schools’ share fell below 5%. (11) Even more alarming, the policy of increasing the weight of final school grades in the 2025 (1404) entrance exam played an institutional accelerator role, structurally favoring well-off students who could invest more in exam preparation. As a result, in the 2025 entrance exam, the share of ordinary public schools among top ranks virtually dropped to zero. (12) These figures demonstrate that the education system is not only reproducing inequality but is actively accelerating class-based segregation and completely blocking paths to social mobility for the underprivileged.

In addition to the triangle of inequality rooted in economic and cultural capital (geographic disparity, commodification, and school segregation), there is a rentier logic embedded in higher-level policies that allocates approximately 30% of the most valuable seats in higher education to specific groups. This system, by introducing a flexible quota threshold and admitting candidates with significantly lower scores, not only undermines the principle of meritocracy but also intensifies pressure on middle-class candidates who lack economic or political privileges. As a result, the student admissions process has become a battleground where success is not merely a function of individual merit but the outcome of a complex interplay of financial means, geographic origin, and access to privileged quotas. This situation starkly illustrates the functional reversal of the educational institution.

The analysis presented shows that class-based education in contemporary Iran is neither accidental nor the product of isolated managerial errors. Rather, it is the structural and multifaceted outcome of three mutually reinforcing mechanisms: geographic disparity, growing commodification, and institutionalized segregation. These elements have combined into a destructive system that renders escape nearly impossible for the lower classes. A child born in a deprived area (first side) is excluded from competition. An urban middle-class student must enter the costly education industry (second side). Finally, the special school system, through student segregation, legitimizes these inequalities by labeling them “talent” and “merit” (third side).

This process has profound and damaging social consequences:

First, by blocking avenues of social mobility, it erodes social capital and delegitimizes the principle of meritocracy.

Second, by reducing interaction opportunities among students from different social classes, it weakens national cohesion over time.

Third, by undermining public education as an inclusive institution, it destabilizes the social contract between the state and citizens.

Ultimately, we can conclude that Iran’s educational system has historically drifted from its ideal function and now effectively contributes to the reproduction and deepening of inequality. This restructuring of inequality presents a fundamental challenge to the future of development and justice in Iran. Any policymaking aimed at confronting it must begin with a fundamental reexamination of the philosophy, structure, and economics of education—a reexamination that starts with acknowledging the painful truth that the school, once meant to be a tool of liberation, has become the most effective instrument of captivity within unequal structures.

Tags

Education and training Education budget Educational justice Gender gap peace line Reza Harisi School Social justice Social stratification Students deprived of education ماهنامه خط صلح