Those Who Love Death/ Arash Mohammadi

I.

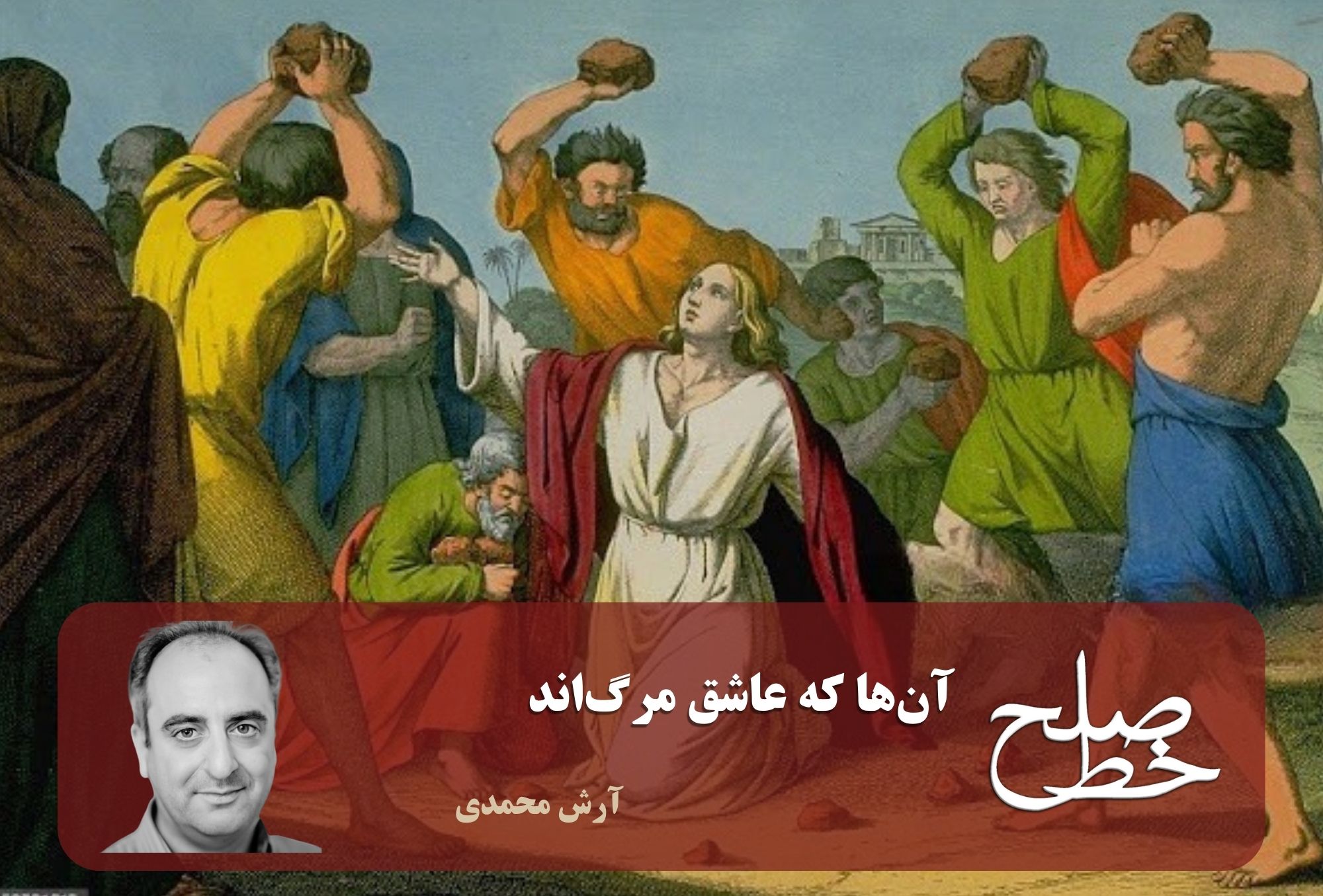

I was a child—perhaps ten years old. I can’t recall my exact age, but I vividly remember walking past the Baqi Cemetery when I heard a scream. A man and a woman were about to be stoned to death. Out of curiosity, I stopped to watch. The problem was that although a large crowd had gathered, I somehow managed to see the mutilated corpses of the two—right at the moment when it was all over and people were gathering the stones.

Now, when I look back at that day, I think to myself: how did that crowd of death-seekers manage to whitewash such a human atrocity? The truth is, as a child or adolescent thirsty for life, I saw no sorrow or regret in the faces of those onlookers. What I saw—what there was an abundance of—was the thrill of witnessing two deaths. The deaths of two human beings, of whom nothing remained but crushed faces and lifeless bodies.

II.

The reality is that after all these years, whenever I think of public executions, I am reminded of those two mangled bodies—of how people stood and watched and casually chatted about how such a death was “deserved.”

I think of the man and woman—who perhaps died the moment the first stone struck their skulls. But their memory, and the imagination of what may have transpired between them, lingered for days, months, and perhaps even years in the minds of those who had watched them die. I say “years” because five years later, when I was in the thick of adolescence, a classmate in our schoolyard recounted the very scene I had witnessed—with one difference: his account was laced with descriptions of the woman’s beauty, though all I had seen was her destroyed face.

III.

The truth is that if the Islamic Republic cannot today carry out executions as freely as it did in the 1980s, it is not because it doesn’t want to—it’s because it can’t. Back then, it could—because it felt the legitimacy and approval of a people who blindly accepted whatever it proclaimed.

I remember a friend whose brother had been executed for alleged cooperation with the Mojahedin. He once told me that the worst memory of his life wasn’t his brother’s death, but the nights of Iraqi air raids. He said, “Our neighbors threw stones at our walls and doors, accusing us of helping the enemy with targeting coordinates.” In those days, whatever the state said was taken as sacred by much of Iranian society. So now, when the regime no longer enjoys such legitimacy, it’s not that it doesn’t want to create mass graves for political prisoners—it simply can’t.

IV.

I’ve said all this to arrive at a brutal critique of Iranian society itself. The truth is that whether in this war-torn and rebellion-ridden Middle Eastern land—or anywhere else on this planet—as long as there is an audience, there will be public executions and state-sponsored killings.

If we still witness this corrupt and incompetent regime—despite all its failures, crimes, and layers of corruption—turning people into actors in its grotesque spectacle of death, it is because audiences still exist who are eager for such horrific endings.

The day Iranian society realizes that every execution, regardless of the crime or circumstance, is a form of state-sponsored killing—and refuses to bear witness—then we will no longer see such disgraceful displays.

The Islamic Republic can no longer send political prisoners en masse to the firing squad. Society will no longer tolerate such collective deaths. And so, the day a collective understanding is born—that every execution is a crime, and watching one is an act of complicity—we will see an end to public executions altogether.

Perhaps it’s time we became eager to witness life instead of death. Perhaps it’s time to dance in Azadi Square, rather than watch someone die.

Tags

Arash Mohammadi Baqi Cemetery in Qom Execution Execution in Malaam peace line Peace Line 173 Public execution Right to life Stone Violence ماهنامه خط صلح