The Pain of Democracy in Iran / Reza Alijani

Comparison of Civil Society in Iran before and after the Revolution

The study of revolution and events of the new government is mostly pursued in a sociological and scientific manner, given the intensity of political pressures after the revolution and the treatment of opponents and critics, as well as the volume of executions. A general conclusion is drawn about the events after the revolution, which in my opinion, has a black and white image and is emotional.

After the revolution, many negative events have occurred; the intensity of violence against opponents and the number of executions are higher than before the revolution. In the field of women’s rights, the beginning of the Islamic Republic was much further behind than the end of the Pahlavi era. In addition, in dealing with certain ethnic and religious groups such as Sunnis, the government’s biased actions stemming from certain ideological and sectarian beliefs were more restrictive and severe than the previous government. However, we must also look at the bigger picture and consider the revolution as separate from the Islamic Republic in order to have a comprehensive understanding. For example, in the field of women’s rights, traditional customs, which made up the majority of society, opened up to their own new world after the revolution and their defensive guard was lifted. It can even be said that with the moral trust that traditional sectors of society had in the government and the new society, these types of families were allowed more presence and activity, such as higher

Even with negative emotions towards the actions of the Islamic Republic, it must be acknowledged that Iranian society has advanced significantly in the political realm. Press freedom, compared to three decades after the revolution, is more open and free, except for limited periods such as the nationalization of oil. With the exception of a period when a young Shah comes to power, especially after the coup of August 28, the political and media landscape of Iran, including civil society, has been a closed and government-made space.

Despite the fact that the leadership of the government gained power after the revolution, it has always been of a highly centralized nature and gradually took on a role similar to that of the Shah in the constitution. However, what actually happened was that even at the height of Ayatollah Khomeini’s popularity, he was unable to bridge the huge gap between himself and other political figures within the power structure. This gap existed during Ayatollah Khomeini’s reign, but even then, there were those who opposed him intellectually and religiously, and in the Consultative Assembly, around a hundred representatives voted in favor of the President, Ayatollah Khamenei, and against the Prime Minister, Ayatollah Mousavi, whom Ayatollah Khomeini had supported. Although this official opposition to Ayatollah Khomeini is considered, in a polarized atmosphere, it did not receive much attention from critics as a political and sociological element. In contrast, these types of

Monarchy and spirituality were recognized as two historical institutions in Iranian society, and the revolution caused the monarchy to collapse. The anti-monarchy revolution within itself was a complete rejection of absolute power, although the subsequent government, with religious biases and later with the power of oil and oppressive machinery, reconstructed this absolute power. However, in the fabric of society and even in certain layers of political power, this power gradually shattered like a broken crystal glass and dispersed. In fact, the current difference between Mr. Khamenei and other powerful figures is not the same as the difference between the Shah and his ministers, for example.

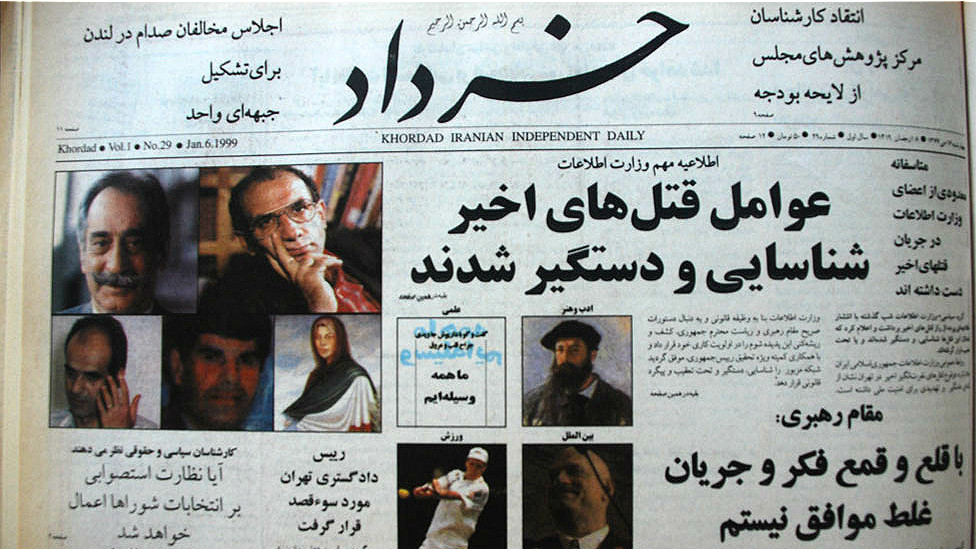

These conditions, of course, are conditions that have been imposed on the government by the general public and educated members of Iranian society; however, at that time there were also great journalists who tried to take advantage of the gaps in the political space, but the level of issues they raised and the quality, quantity, and layers they had to criticize are not comparable to the present. For example, during the period of reforms, with the revelation of the government’s covert operations in relation to serial killings and executions in 1967, the government’s behavior came into serious question. Just as with some cultural and religious discussions, the fundamental theory of the government, namely the principle of the rule of the jurist, came into question and lost its credibility. Overall, it must be said that although the space has become more closed in recent years, attention to the level of corruption in various political layers and attention to institutions directly under the supervision of the leader is much more than what was seen in the past.

During that time, there were various people’s institutions, such as a series of women’s organizations, which were either created by the government or closely tied to it. There were also charitable institutions, mostly affiliated with religious groups, or some scientific and research societies, which did not have much of a social participatory role. The most progressive associations were student, literary, and sports associations, and they did not have as much influence on society as they do now. However, today we have civil institutions in various layers of society that focus on preserving the environment or addressing social issues such as child labor, street women, and drug addiction. There are also civil-national institutions present in different provinces of the country, especially in Kurdistan.

Justice demands that we see these things; although it must be emphasized that these are not due to the kindness of the government, but rather due to the growth of civil society and its prosperity. A society that becomes prosperous exerts pressure and power, and this power no longer has the huge gap between the top and bottom of the pyramid, due to the occurrence of the revolution, and we see that every opportunity that arises reduces this gap and criticism becomes more serious or there is more diversity in it. As a result, due to qualitative growth, Iranian society has been able to put pressure on the government in various forms, both individually and collectively, in the form of civil institutions, and impose itself and the civil space – meaning the space between political power, citizen, and family – is a stronger and wider space compared to the pre-revolution era.

In regards to the discussion about women, we must pay attention to the fact that Iranian society during the revolution was a traditional society dominated by traditional values. During the revolution, 55% of Iranian society was rural and 45% was urban, and this 45% urban population was mostly traditional. Therefore, there was a desire for renewal in the more limited layers of women, who were also suppressed by the speed and intensity of the Islamic party. After the revolution, although leftist and secular women were forced to adhere to a series of red lines such as mandatory hijab in order to return to the public sphere, if we consider all women, we see that the majority of women who used to wear chador have now switched to wearing manteau, which is a step towards changing their lifestyle. This change can be considered as a universal change, from villages to cities. Despite the government’s efforts to impose its own version of hijab, in universities and offices, the style of dress is

All of these factors show that Iranian society has undergone a historical transformation; a society that was once disorganized and dominated by traditional values during the revolution has now become a modern society with a dominant modern outlook in the post-revolution era. This not only manifests itself in all areas, but also imposes itself on the government. In fact, the pressure from this civil society, under the pressure of the government and its repressive machinery, has transformed the society. This issue is rooted in other factors as well. Fundamental changes such as the shift towards urbanization, increase in higher education, growth of women’s social and cultural presence in education and employment, and rapid technological advancements and the subsequent rise of mass and communication media, are all examples of influential factors in this transformation. It is through these changes that society becomes aware of its rights and the citizen emerges as a philosophical subject, thinking for themselves and gradually distancing themselves from external authorities. The citizen also feels like a member of a larger society and as such

All of this reflects the changes and growth of Iranian society. Despite the fact that the government of Iran has always been a turbulent and abnormal government in the region, and there have been significant pressures resulting from challenges such as the revolution, hostage-taking, war, and nuclear policies, which have also affected the society, and this society has been struggling in recent years with very difficult economic conditions; but we are witnessing the rapid growth of this society under pressure. In this regard, we must emphasize the young generation, especially young girls who are very dynamic and active. About 70% of Iran’s population is under the age of 30-35; and based on this, sociologists like Habermas predict the future of Iran: “The young people of Iran will make its future.” And Allen Thorn says, “If you want to see how the future of Iran will be, look at what is going on in the minds of its young girls!”

So we see all of these in the fabric and structure of society, and civil society and different classes and layers of society continue their gradual and sometimes rapid movement towards it, and the government is still in the alley, for example, women can or cannot have solo performances, or are still caught up in the twists and turns of guidance and prohibitions and the like.

In the realm of women, I see revolutionary movements and advancements compared to the pre-revolution era that have no connection to the government. The government may hinder these movements, but they are so fundamental and powerful that they overcome government obstacles; such as the women’s movement, which has not only influenced power but also opposition and critics.

Of course, mentioning these issues should not lead to the incorrect assumption that we ignore the violation of human rights after the revolution or even see less of it compared to the Shah’s regime. It is like the story of the mouse and the cat of Abid Zakani, where when the cat became religious and Muslim, it would catch five mice at a time, or as Sharifati says, “Woe to the day when force is dressed in piety.” Now, force is dressed in piety and the level and extent of oppression and violence is even greater. The issues mentioned earlier were based on a bottom-up perspective. As mentioned before, with a comprehensive societal perspective, we cannot present a simplistic black and white comparison of before and after the revolution.

From this perspective, I also believe that Iranian society has experienced a leap in growth, despite all the pressures, oppressions, restrictions, and discriminations that are imposed and the stubborn resistance of those in power against the natural movement of society; these challenges and struggles are actually the pains of democracy in Iran, in an oil-rich country. Of course, the seeds of such growth were planted before the revolution and if it weren’t for the oppressions of the 1960s, it could have moved even faster and we could have witnessed the second of Khordad 76 at least a decade earlier.

The civil society of Iran and the spectrum of political participation have shown that they are willing to advance their demands peacefully, but a large part of the future of this matter is in the hands of the government. In essence, the key to the transition to democracy in Iran is more in the hands of the government than the society. This means that the society is moving forward and it is the government that can advance this process based on national interests and the overall well-being of the society, and allow it to progress. Otherwise, unfortunately, this cycle will be disrupted and it is uncertain how and with what process these demands will move forward.

Created By: Reza Alijani

Created By: Reza AlijaniTags

Civil society Democracy birth Magazine number 46 Monthly Peace Line Magazine Reza Alijani The Revolution of Bahman 57