In an attempt to return to the era of traditional schools.

The story of the agreement between the Tehran Department of Education and the seminary to affiliate a certain number of public schools with the seminary is probably not in need of reminding, and esteemed readers may have already read about it in other publications or at least in this issue of the peace journal.

Based on this argument, there is no need to mention the commitments of the Ministry of Education towards the seminary sector, nor to address the fact that previously, the management of 4200 schools had been handed over to the seminary sector.

From this, we can focus on the background and consequences of the news without paying too much attention to it. Regardless of the practicality of such a plan, these actions can be seen as an effort to revive the culture and structure of home schooling, a structure that in the not-so-distant past was managed by clergy or their followers and gradually, with the rise of the Constitutional Revolution and later modernization of educational institutions, was taken out of the hands of the clergy through resistance. Although the phenomenon of religious rule is relatively recent in Iranian history, education and upbringing have already been tested with a religious model and by looking at its history and function, it can be understood to what extent this model has been effective and successful despite all the changes that have taken place. Beyond that, not only by examining the history of scholasticism in the Middle Ages in the West and also the seminaries in Iran, but more accurately by looking at the current experiences of countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan

The reader can easily make such an evaluation and there is no need to elaborate on it. It may be more appropriate to mention the history of the emergence of new schools in Iran and how the proponents of the old method, namely the traditional school, faced the modern education system. It seems that the recent document is also a continuation of this historical competition between the two mentioned methods.

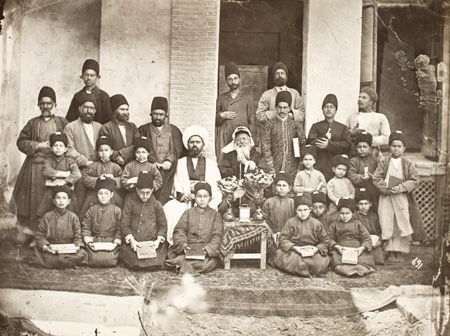

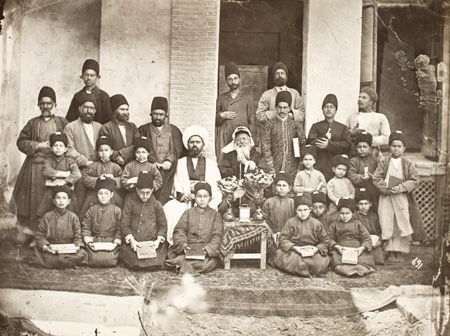

The establishment of a new method of education and upbringing in Iran is owed to Mirza Hasan Tabrizi, who later gained fame in Rashdiye. He was the son of one of the scholars of Tabriz and even at the age of twenty-two, he was the imam of a mosque in Tabriz.

Rashdieh, in her youth, read an article in the Soraya magazine that shook her deeply. The article stated: “In Europe, one out of every thousand people is illiterate, while in Iran, one out of every thousand people is literate. And this is a result of poor educational principles.” (3)

This text is about him thinking about reforming the education system in Iran. After traveling to Beirut, Istanbul, and Egypt and researching new teaching methods, he founded the first Iranian school for Muslim Caucasians in Yerevan. The people there were more eager to see modern Russian schools for education, so he was able to teach reading and writing to students in just sixty hours using innovative teaching methods. (4)

After four years of successful experience, Naser al-Din Shah, who returned from his second trip to France to Iran, visited the Roshdieh School while passing through Yerevan and asked Roshdieh to return to Iran to establish a similar school. However, the zealots explained to the Shah that establishing a new school would promote secularism and pose a dangerous threat to the monarchy. As a result, Roshdieh was caught up in the difficulties of founding a school in Iran for a long time. He finally established his first school in Tabriz in 1305 AH. The enthusiasm of the people to educate their children, and with such ease, caused the school market to thrive. However, the traditional school owners, who saw their shops empty and saw the progress of the new school as against their interests, became agitated and forced the Grand Mufti, one of the ignorant scholars, to declare Roshdieh an apostate and issue a fatwa

From then on, the story of life was a constant struggle between growth and decline, until the time of death. It was a story of perseverance and unity in the face of establishing new schools on one hand, and the condemnation and attacks on these schools by the traditionalists and their escapes and returns to continue their work. In this journey, he was beaten countless times, his hands and feet were broken, he was wounded by bullets, his schools were destroyed, and even several students were killed.

In a meeting that Roshdieh had for convincing the clergy, according to him, one of the gentlemen who had a higher position than his worth couldn’t restrain himself. He said, “If these schools are expanded, meaning all schools become like this school, after ten years, we won’t find a single illiterate person. It’s clear how much the market for scholars will thrive then.”

Mirza Hassan, the manager of Rashdiyeh School, went to Tehran after working hard to establish schools in Tabriz. The holy cries of the saints were raised that the end of time is near; a group of Babis and non-religious people want to change the alphabet and teach the children the book instead of the Quran. In a meeting, Sheikh Fazlollah Noori says to Nazem al-Islam Kermani about the new schools: “I swear to you by the truth of Islam. Are these new schools against the law? Is entering these schools equivalent to the decline of the religion of Islam? Does studying foreign languages, chemistry, and physics not weaken the beliefs of the students?” (6)

It now seems that attaching schools to seminaries is a continuation of the same concern of the clergy; of the impact of new schools on the decline of the religious market. But regardless of the correctness or incorrectness of this idea, the problem is the criticism that can be brought to this plan. It is clear that presenting such a plan has caused concern and dissatisfaction among teachers and major educational experts.

Critics have pointed out that entrusting the education of students to clerics is against the constitution; not only because if parents agreed with such plans, they would have sent their children to seminaries instead of schools from the beginning, but also because the education system is under the management and responsibility of the Minister of Education and even more importantly, the government, which has been entrusted with the people’s vote of confidence. “Seminaries have no place in the constitution and no authority is accountable to the people. It is not enough to say that the Minister of Education is overseeing this, as the explicit text of the agreement has given these rights to the seminaries. Right now, inspectors from the seminaries are going to schools in Tehran to enforce their rules. On what basis has the Minister of Education of the government entrusted the people’s right to oversee?” (7)

But despite the illegality of such an agreement, why is the academic community willing to implement such a plan? Critics accuse the seminary of seeking financial gain for their new clerics and recruiting new forces in an environment where there is no enthusiasm for young people to become students. It seems that this accusation is not only voiced by critics, but supporters of the seminary plan also confirm it in a different language.

But the fundamental question in this matter is: How can the clergy, despite having the most positions and government positions, mosques, radio and television, shrines, Basij bases, supervisory offices in the armed forces and universities, and so on, and despite having huge budgets, have been unsuccessful in attracting young people and even the general public to religion? How can they claim to be successful in schools? Undoubtedly, the answer of the clergy to this question cannot be easy, given their unsuccessful track record.

Hirana News Agency, 6th of Dey month, 1392.

BBC Persian website, 25 December 2013.

3- According to the free encyclopedia Wikipedia, the entry for Hassan Rashdieh.

4- Ajoudani, Mashallah, Iranian Constitutionalism, Akhtar Publications, Tehran, 1386, p.261

Previously, pages 265-267.

6- Kermani, Nazem Al-Islam, The History of Iranian Awakening, Part One, Volume One, Rudaki.

7- Ramazanpour, Ali Asghar, about entrusting children to clerics in schools, website of the Democracy Center for Iran, 18 December 2013.