“What have women done for the revolution, and what has the revolution done for women?”

Iran before 22 Bahman 57

In the years before the revolution, there were no special organizations or associations for women in Iran. The revolution also did not initially have any special intentions for women. It was a general revolution against the dictatorship of the Shah and its associated relationships. The revolution aimed for freedom, a better life, and the full participation of women in economic, social, and political spheres, as well as achieving equal rights for women and men. It was a mass movement in which women and men actively participated and were partners in the revolution. “All together” was the backbone of the revolution. In this atmosphere of “all together,” women’s demands and attention to their desires were somewhat ambiguous. Interestingly, even in the culture of protest in society, which was heavily influenced by the fervor of the revolution, whether in political groups such as Marxist or Islamic, or in the intellectual space of poets and writers, women and men actively participated. During the revolution, no one could even imagine how, in a very short period

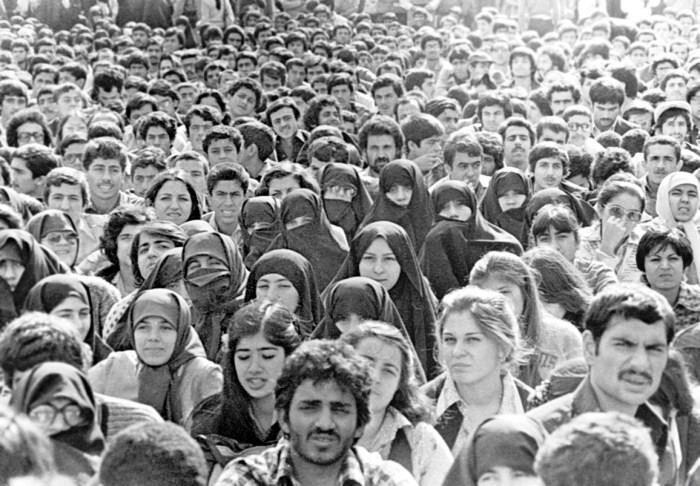

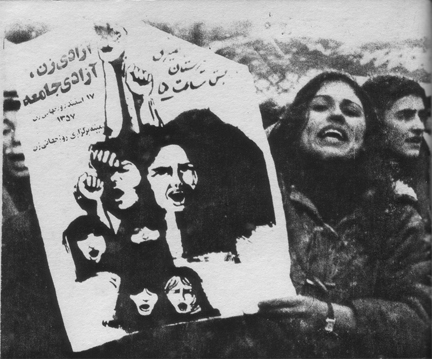

Women played a significant role in the 1957 revolution and in the fight to overthrow the Shah; whether in the midst of protests outside the boundaries, in marches and strikes, in fortifications and university poetry nights, or in political groups of that era, women had a prominent role. It is not enough to say that women participated and had a prominent role, this does not fully acknowledge their contribution. The 1957 revolution was the first major political experience for women in the history of Iran and, in terms of participation and presence, it was fundamentally a feminist revolution. In fact, the hardworking women and students were the main pillars of the 1957 revolution.

A brief look at the pre-revolution era in the field of women’s issues.

1307- Women have gained access to educational scholarships for studying abroad.

1314- The first co-ed elementary school was opened with the discovery of the veil.

In 1317, women, without any restrictions, found their way to the University of Tehran.

1323 – The Compulsory Education Law was approved.

The High Council for Women’s Societies was formed.

1341 – Women were granted the right to vote.

In 1342, women were elected as representatives to the parliament.

In collaboration with various women’s associations, the “Iranian Women’s Organization” was formed in 1345.

1346 – Women’s entry into the political staff of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

– Women were granted the right to serve as judges and join law enforcement forces.

– The Family Protection Law was passed.

1347 – The first female prime minister joined the government.

– The law for women’s social services was passed.

– The first family welfare center was opened by the Iranian Women’s Organization.

In 1347, women joined the ranks of the Revolutionary Guards.

In 1349, women were elected as members of the city, county, and provincial associations.

In 1354, the Family Protection Law was revised and Iran participated in an international women’s conference. The first woman reached the position of advisor minister for women’s affairs.

1357- The national action plan was approved.

In this year, two million Iranian women were officially employed. 187928 women were studying in universities and in specialized fields. 146604 women were government employees, of which 1666 held managerial positions. 22 women were members of parliament, two were senators, one was a minister, one was an ambassador, three were deputy ministers, one was a governor, five were mayors, and 333 women were representatives in county and city councils.

It must be emphasized that although women were forced to wear the hijab before the revolution, it did not mean that there was enlightenment among women and they were consciously encouraged to enter the social sphere. During that time, the dominant mindset among women was the necessity of fulfilling the traditional roles of being a cook and a mother. This view still existed during the revolution.

Iran after 22 Bahman 57:

The “dictatorship” and “dualistic” monarchy government collapsed and was replaced by a government born out of revolution. The first remarks regarding women’s basic rights to choose their attire were made by Mr. Khomeini on February 16th, 1979 at the Rafah School: “There should be no sin in the Islamic Ministry. Women should not come to the Islamic Ministries naked. Women can go, but they must be veiled. They can go and work, but they must be veiled according to Sharia law.” (Kayhan, February 16th, 1979, issue 10655, page 1)

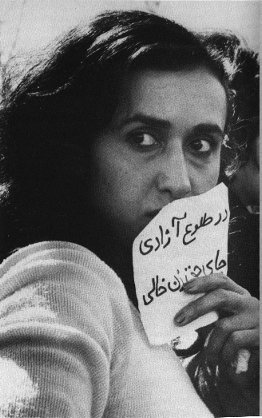

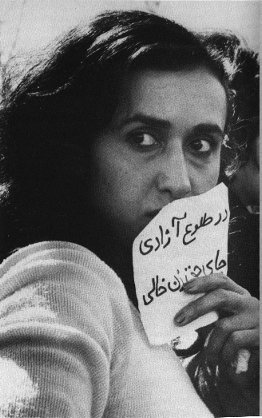

In the photo, it was evident that the wave of social protests had taken over. This was happening while the sound of their knives clashing against women and government newspapers could also be heard.

Following the issue of hijab and the expression of different opinions by clerics and officials, different sections of the society had different positions on this issue. Among them, religious people supported Islamic hijab and considered those without hijab as disrespectful, causing disturbance in the country. Although there was no specific law for how to dress, these people believed that after the victory of the revolution, everyone should become religious or at least appear to be religious. As a result, after the revolution, if the Pahlavi government was removed from Iran, the people themselves, who naturally had different tastes and interpretations of religion, became divided. In the midst of this, since the religious forces were more numerous and were supported by the clergy, they were able to take control of the affairs. For this reason, other groups who considered themselves involved in the victory of the revolution demanded to present their opinions in the structure of government and legislation, and saw the absolute rule of the clergy as a violation of freedom and the fundamental

Experience has shown that when governments enforce something as mandatory without providing a platform for public acceptance and persuasion, it leads to a political culture and social approach that is contrary to the intended reaction and ultimately results in various forms of forced and hidden mobilization. Two concrete examples of this can be seen in relation to the phenomenon of women’s covering (hijab); both during the time when it was forcibly imposed by the order of the Shah and after the revolution when it became mandatory by the decision of the parliament and not adhering to it was considered a violation of public morality and a crime against decency.

According to Article 638 of the Islamic Penal Code, women who appear in public places and streets without observing the Islamic hijab will be sentenced to imprisonment from 10 days to 2 months, or a fine of 50,000 to 500,000 rials. This article is under a section that deals with the punishment of individuals who engage in forbidden acts or commit actions that, although not punishable by law, violate public decency.

Before the mandatory hijab, there were resistances from unveiled women. But after the hijab became a law and unveiled women were confronted and cleansed from workplaces, even opponents began to adhere to the mandatory hijab, to the extent that we no longer faced the phenomenon of unveiled women in society. However, due to disbelief, some groups of women gradually formed the negative phenomenon of improper hijab as a protest against it.

On the other hand, since the limits and boundaries of religious veil were not specified by the legislator and personal opinions were followed, gradually women were confronted for reasons such as not observing the veil or improper veiling.

Female employees who did not observe the hijab in offices, according to the law, were subject to written reprimands or dismissal from their positions as a result of administrative violations.

On this basis, it was because:

In the spring of 1358, the law of protection of the family was officially announced and gave way to civil courts, which entrusted the right of divorce to religious authorities.

In the spring of 1958, the age of marriage for girls was reduced from 18 to 13 years old. At the same time, girls who were married were prohibited from attending high school and a large number of them were deprived of education.

In the spring of 1958, women’s right to judgment was taken away. Women were no longer able to study in the field of judicial law and law interns protested and rebelled.

In the spring of 58, mixed high schools were also not spared from the “revolutionary” decisions and it was announced that these schools must be closed. As a result, high school girls who did not have an independent school were left wandering.

In the spring of 1958, the government took action to restrict the operation of childcare centers in factories and offices. The Central Bank, Ministry of Water, Planning and Budget Organization, Starlight and Mino factories were among them. These actions were met with protests from women.

In the spring of 1358 (1979), family welfare centers were closed and centers for child assistance and family planning were limited. Social workers who were employed in these centers were laid off from non-specialized services. Distribution of birth control pills was greatly restricted and only available to women over 40 years old. The Iranian government implemented all of these measures before drafting its constitution.

As mentioned, the dominant discourse during the 1357 Revolution was populist. This populism was also mixed with violence. The prevailing atmosphere, language, and leadership during the Bahman Revolution imposed a lack of attention towards women’s rights. When we look back from the platform of the future, we see that democratic demands and human rights were not addressed, and of course, women’s issues could not be at the center. After the Revolution, a significant transformation took place in the lives of Iranian women. Four major changes shaped the lives of Iranian women in a different way. In this regard, Mehrdad Darvishpour writes: “The four main axes of post-revolution politics regarding women were still in place:

1- Forcing the veil, 2- Separating women from men, 3- Emphasizing the role of women as mothers and wives, 4- Emphasizing the difference in privileges between men. (Women’s challenge against the role of men, page 73)

In 1982, the part-time work bill for women was passed and most women left full-time jobs and started working part-time. A retirement plan was established and women were able to benefit from retirement benefits and rights after 15 years of work. Women were asked to stay at home and open up opportunities for unemployed men. In the 288th session of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution in 1992, homemaking and raising children were recognized as the biggest responsibility and job for women. Most of the responsibilities of women were limited to feminine jobs such as midwifery and education.

Furthermore, according to Article 54 of the draft of the Islamic Labor Law, married women must have a work permit and social activities from their husbands when seeking employment and hiring.

Despite all the political and economic upheavals in our country, such as the Iran-Iraq war, men’s participation in the war, expansion of government sectors, urban population growth, and the need for cheaper labor for economic progress, the entry of women into the workforce and their collaboration with men was accepted. It is clear that education, knowledge, and skills in any field pave the way for this acceptance. While most men with high school education had a better chance of finding employment, women with the same level of education could not easily find work. Therefore, Iranian women made great efforts to attend universities and higher education institutions and rose up against staying at home and unemployment; to the point where the number of female students in every field exceeded that of male students.

A brief look at what happened to women after the revolution.

1358 – Cancellation of the Family Protection Law; Deprivation of Women from Employment in the Judiciary; Forced Veiling of Women; Separation of Women and Men on Beaches and Sporting Events; Women’s Protests Against the Imposition of Islamic Veil and Cancellation of the Family Protection Law.

In 1359, with the approval of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Khomeini is chosen as the Supreme Leader and Islamic laws and traditions determine the role of women in the family and society. With the start of the Cultural Revolution, universities in Iran are closed. Women are given the right to participate in general elections while adhering to Islamic standards.

1360 – The boundaries of women’s rights and freedoms are determined by the fatwa of the Supreme Leader, especially in cases of disagreement between the Islamic Consultative Assembly and the Guardian Council.

According to Islamic laws, women are deprived of the right to custody of their young children after separation from their husband; elementary and high schools are exclusively for girls or boys.

1362 – Special police patrols against non-Islamic hijab begin.

In 1368, the exclusive right of divorce by the husband is deferred to special courts, based on Islamic criteria.

In 1373, women are allowed to serve as legal advisors in specialized family courts.

1376 – The Human Rights Watch organization awards its prize for defending the rights of women and children to Shirin Ebadi; in the presidential elections, a large number of women vote for a candidate – Mohammad Khatami.

The 1377 law passed by the Islamic Consultative Assembly requires the presence of a female legal advisor in courts handling child custody cases.

In 1379, the number of female students entering universities is higher than the number of male students; female students at Qom University protest against being deprived of taking some courses due to the lack of female professors by holding demonstrations in front of the university…

Comparison of the current situation and pre-revolution status of women in Iran

After the revolution in Iran, a young mother was sentenced to death for killing a man who she claimed was attempting to rape her. The judge had said, “The way she was dressed had prepared the ground for his assault.” Many women have been sentenced to suspended prison terms for promoting egalitarian ideas, and the Guardian Council of the country has withdrawn from the 1981 United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

During the time before the revolution when women were granted the right to vote, the first protest was led by Mr. Khomeini. Polygamy had also become illegal and divorce laws were based on equality between men and women.

The revolution promised equality and justice for women, but after three decades, women are still deprived of both. Instead of following a flexible legal approach that is compatible with Islamic law and promoted by Ms. Ebadi, the Islamic Republic of Iran promotes what Farideh Ghirat, the leading advocate for women’s rights, calls the “dry bone version”.

After the revolution, Iran revived polygamy, made divorce almost impossible for women without the consent of their husbands, and condemned women as “adulterers” and subjected them to stoning.

Following the rapid growth of the population in the first decade of the revolution, family planning reduced the national fertility rate to two children. The average life expectancy for women is seventy-two years, which is two years longer than men. In 1975, the illiteracy rate among women in rural areas was ninety percent, and in cities it was over forty-five percent. Currently, the literacy rate among girls aged fifteen to twenty-four has reached ninety-seven percent. In previous years, the number of female students in state universities was higher than that of men.

Despite the increase in the number of educated women and considering inflation, there are not many families who can live off the income of one person. However, the economy is not able to create jobs to attract these women.

“A historical movement” has begun in Iran. Nowadays, many girls in different provinces of Iran are getting married to the boys they have chosen, not the ones their parents have chosen for them; a decade ago, this phenomenon was unknown. However, some parents feel threatened. In a tragic incident, a father from Shiraz prevented his daughter from pursuing her accepted Bachelor’s degree and burned her alive.

Before the revolution, two women were present in the government.

After a lot of conflict, the age of female maturity has increased from nine to thirteen years, and dowry is now considered due to inflation. Girls can also receive scholarships for studying abroad.

In the past few years, 150 women have been engaged in activities in non-governmental organizations in Iran.

The transformation of these institutions into effective supporters of women’s rights takes time, but these organizations provide a way for Iranian girls to introduce and express their identity.

Non-governmental organizations are highly vulnerable to the fear of conservatives in civil society.

Domestic violence, infidelity, and AIDS have multiplied several times.

The sale of family values in Iran has had consequences: one third of marital bonds lead to divorce, while twenty years ago divorce was rare. However, judges who show sympathy towards women seeking divorce are few. Women are often forced to give up their dowry in order to ensure their husband’s agreement to divorce.

Issues such as profanity and addiction are prevalent in Iran.

No one knows how many Russian women are in Tehran, although their presence on the streets suggests that their number reaches tens of thousands. There is also a debate about one issue: the majority of these women are self-sellers, girls who have fled from poor and destitute families, and their number increases every day and their age decreases.

In Iran, special attention is given to the poems of Forough Farrokhzad, an Iranian poet. Forough used to say:

Social changes in Iran have given new meaning to concepts such as religion, ethics, and love.

But after forty-five years have passed since his time, such statements can imprison the speaker, but the judges of the Islamic Republic cannot prevent the young Iranian women from solidarity with this perspective.