The story of the pain of defending in the judicial system of the Islamic Republic / Ali Kalaii

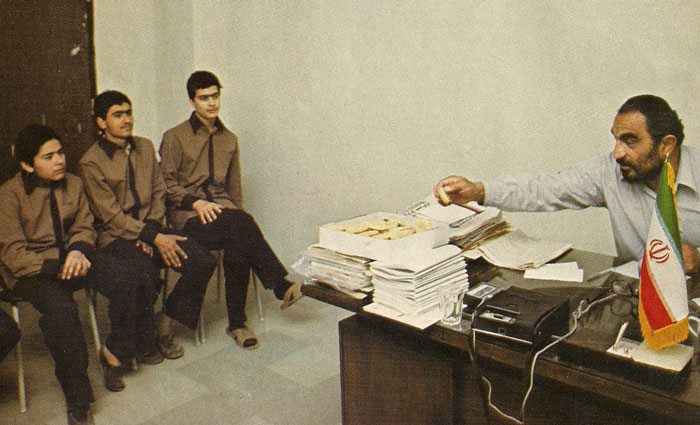

This is a caption

Every person, when accused of a crime, has the right to defend themselves based on human reason and logic. Whether their defense is audible or inaudible is another matter. But the principle of the matter cannot be violated. The principle that is also mentioned in the first clause of Article 11 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This clause explicitly states that: “Everyone charged with a criminal offense has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a public trial where all their rights to defend themselves are guaranteed.”

But the story of defending oneself against false accusations in Iran after the victory of the revolution in February 1979 is of a different nature. It is a bitter story that even clashes with the fundamental principles of the constitutional laws of the post-revolutionary system. Article 35 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran explicitly recognizes the right to defense and, due to the specialization of legal matters in the modern world, considers the issue of hiring and appointing a lawyer as a legal right for individuals who are knowledgeable about laws and legal provisions. This article explicitly states that: “In all courts, the parties have the right to choose a lawyer for themselves, and if they are unable to choose a lawyer, facilities must be provided for them to appoint a lawyer.” However, this article designates the issue of the court as the place for choosing a lawyer. That is, before that, in the preliminary investigation stage, there is another matter involved. The same stage that, due to the lack

We follow the story from the days after the revolution. Days of rooftop schools and executions with the identification of Khalkhali; and then the days after Khordad 60 and the arrests of hundreds and thousands of Iranians. Minute courts and death sentences and counting three hundred and four hundred bullets released by prisoners who later, after being released, spoke of the tragedy. Courts and executions that in Mordad and Shahrivar 67, in Iranian prisons, took the lives of thousands of Iranians. But was this fundamental right, meaning the employment of a lawyer and the presence of a lawyer, raised in those days, both in the preliminary stage and in the court stage?

“Taqi Rahmani, a national religious activist who was imprisoned during those days in the prisons of the Islamic Republic, does not consider the issue of lawyers to be raised during that time and says: “Even this issue did not cross my mind.” Reza Alijani, another national religious activist who was also imprisoned during the 1960s in the Islamic Republic, tells us that: “Neither the issue of lawyers nor the courts had any resemblance to the courts of present-day Iran.” Alijani also says that: “The accusations were not based on legal grounds and common interrogation methods were considered as charges.” In response to a question about whether the demand for lawyers was raised or not, or if this issue was even considered, Alijani says: “No, it was not. Under torture, you no longer think about lawyers. It’s like asking someone who wants to arrest you for a warrant and they show you their weapon.”

We asked this question from two women who were members of left-wing groups at the time. Monireh’s brother describes the situation of lawyers in those days and years as a “joke” in his conversation about peace and talks about the “courts” that lasted only a few minutes, where the religious judge was also the prosecutor. He explains the situation of those days as follows: “Most lawyers retired during that period, the Bar Association was dissolved, and many lawyers were forced to leave the country.”

But Mrs. Saberi is a different kind of human. A mother with two children who can’t even find the time to gather basic supplies for her young children’s treatment in prison. Mrs. Saberi, whose husband Abbas was one of the executed in 1988, like other prisoners of that time, has no access to a lawyer and generally rejects the discussion and relevance of a lawyer, saying: “We were arrested, interrogated, and then they would call us and take us somewhere where there was no court. They would read the charges and without letting you speak, they would give a sentence and sometimes these sentences were not even communicated in writing.”

Saberi also says: “They didn’t let us at all. They would ask us some questions and if we said anything, they would hit us with the same case. In this situation, we couldn’t speak to a lawyer and it was impossible to bring it up. We knew we had to have a lawyer and according to international standards, we had to be tried. We knew all of this, but they never allowed us to speak. When they arrested me with my two children and wouldn’t let me breastfeed them, what more can I expect from this situation?”

This lady admits that during those years, the prison guards and court officials never considered her (according to her own words) as a “human” and would tell her that she was among the “forgotten”. Saberi believes that the reason for this lack of recognition is the difficult and harsh conditions and gives the example of the peace line: “When Kianouri was arrested, everyone would declare that they should be tried according to international standards and with a lawyer. But even they were not given this right. Even someone like Kianouri did not have the right to a lawyer.”

This suffering woman, who has lost both her husband in the executions of ’67 and her two children who were raised like the essence of life in the prisons of the Islamic Republic during the 1980s, says that in response to every question and demand, the answer of the prison guards was: “Do you think you’re in a hotel?!”

But being sentenced and imprisoned was not only limited to adults. Javid Tahmasbi, a fifteen-year-old, who has spent the years between 1960 and 1965 in prison for supporting the organization of Mujahedin-e Khalq Iran, also has his own account. This account is not just that of a prisoner, but of an individual who has transformed from a 15-year-old child to a 20-year-old adult in prison. Crossing the age of eighteen is a memorable milestone for a person, and Tahmasbi’s passage through the prisons of Iran has taken place during this time.

Javid Tahmasbi, emphasizing the “humorous” nature of the court proceedings during that time, considers the duration of trials to be between two to five minutes. He, who was arrested in November 1981, speaks of the peace accord: “The group of detainees during those years were individuals between the ages of thirteen to eighteen, and at that age, they generally did not know anything about the law to demand anything.” He continues: “The religious judge, such as Mohammadi Gilani (whose verdict was signed by the religious leader, Ruhollah Khomeini) and interrogators like Sadeq Asadollah Lajvardi, known as the “Tiger of the Judiciary,” played the role of all judicial authorities, and the lives of individuals were in their hands.”

Tahmasbi also says that he was a witness in the trial of Dr. Mohammad Maleki, the first president of Tehran University after the victory of the revolution, who spent the years 60 to 65 in prisons of the Islamic Republic. He (Tahmasbi) was shown as a black mark in the court. Javid Tahmasbi talks about the absence of a lawyer in the court for someone with an academic rank and university position like Dr. Maleki, and quotes, “They only read the verdict and filmed.”

What can be observed from the coordinates of the testimonies of the five witnesses of the prisons of the 1960s and during the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran based on the principle of guardianship of the jurist, is that the demand for this human right was not imaginable or imaginable at that time and its demand was considered a bitter and oppressive joke. The prisoners of that era did not have the minimum basic rights of a prisoner, which is the right to have a lawyer, and this meant the suspension of one of the human rights of individuals in those days and the violation of one of the most fundamental rights of a human being.

But we follow the story after the death of the founder of the Islamic Republic system. The war has ended. The massacre of the 1960s and 1970s – which Reza Alijani, a nationalist religious activist, considers an Iranian Holocaust – has taken place and a great genocide has occurred. It is a time of construction and a new leader. But it seems that this fundamental right is still ignored and unread.

Taqi Rahmani, who is currently a witness and prisoner in jail, says: “After the year 1368, the discussion about lawyers came up, which was another form of occupation, and this time it was due to the arrival of Galindoople to Iran, and in this way, lawyers were hired.” This means violating the basic human rights of individuals, and this time it was through manipulation and forcing a lawyer to confess; a person from the ruling class who, according to Rahmani, showed “compassion” or tried to make the accused express regret in order to receive a lighter sentence, all out of fear of inspectors and special reporters of the United Nations. This means that the legal and judicial institution, which is supposed to be impartial and speak based on legal arguments, had turned into another element of the ruling class at that time, in order to suppress and deal with political opponents in a different way. In the previous decade, they would kill, but now they take

Another point regarding these years is the return of Assadollah Lajevardi to the management of Evin Prison. Evin, which had reduced the number of political prisoners through mass executions in the summer of 1967, is once again under Lajevardi’s control, who had been removed from his position by the Supreme Judicial Council in December 1984. Lajevardi’s return is not just the return of one person, but the return of the same atmosphere that dominated Iranian prisons in the early 1990s. The same level of violence and cruelty. The case of the “90-signature letter” criticizing the policies of Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was the president of Iran at the time, and the subsequent arrest and physical and psychological pressures described in the book “Haji Agha’s Guest,” are only a part of the dark actions of those years; and it should be added that the president at the time, Hashemi, and the head

June 1976 marks the beginning of another uprising; the demand for basic human rights. Since December 1977 and the events of the political assassinations in the fall of that year, which became known as the chain murders, the issue of hiring lawyers once again became a matter of life and death. The Bar Association took a breath and step by step moved towards becoming a center for lawyers’ rights. Although independent lawyers have also paid the price for their independence and refusal to accept the rule of the government (such as being imprisoned, like the lawyers of the chain murder cases), they still stood their ground and continued on their path.

If in the first decade, the approach was to eliminate lawyers and massacre prisoners, and in the early years of the second decade, it was the era of white torture and occupation lawyers, then after Khordad 76, the stand of lawyers and their clients on one side and the intimidation of the entire judicial system, which also closed down the prosecutor’s offices, and the judge became everything except a judge. The prosecutor and the judge became one, and Saeed Mortazavi and Haddad in the era of Mohammad Yazdi went on a rampage. To the point that Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, who was appointed by the leadership of the system as the head of the judiciary or, according to Dr. Abdolkarim Soroush, the butcher’s power, spoke of taking over the ruins and gave the news of new reforms in the judicial system.

The struggle between independent lawyers and defendants continues and persists against the lawless rule and unjust judges of the revolutionary courts. In the years after June 2009, if before that, every now and then a famous lawyer was arrested (like Shirin Ebadi in the case of “Tape Makers”, Nasser Zarafshan, the late Saffari, Dr. Dadkhah and others), this time strange and bizarre sentences were issued, and even the suspension or revocation of lawyers’ licenses, or attempts to approve the qualifications of lawyers by a non-lawyer entity, other than the Bar Association, were made to deprive defendants, activists, and all those who needed legal defense in the courts of the Islamic Republic of their fundamental and legal right to have an independent lawyer. The sentences of Dr. Saeifzadeh and Abdolfattah Soltani, or the imprisonment and suspension of the esteemed lady Nasrin Sotoudeh, and the harsh treatment

In addition to being informed about current events and decisions, during the post-revolution period of Bahman 57, the accused did not have the right to have a lawyer during interrogation. This means that during interrogation, the interrogator, the detainee, and the interrogation room were all under the control of the security forces from 209 to 2,000 to 36 in Seoul. Recently, and under the new Criminal Procedure Code, this right was suddenly given to the defendants. A strange matter in the judicial system of the Islamic Republic era. But with a caveat. A caveat that smells of a return to the era of occupied lawyers or even not having a lawyer at all.

This clause states in simple language that in cases of security offenses or organized cases (such as parties, groups, and organizations that often engage in political activities and are closely related to the current government), the accused can choose a lawyer from among the approved lawyers by the head of the judiciary. The names of these lawyers are also supposed to be announced by the head of the judiciary.

The subject is simple. In crimes that the government considers as security-related, but in reality are political, the judicial system does not trust all lawyers. This means that after more than three decades of violating the rights of lawyers and the principle of advocacy, and after confiscation, imprisonment, suspension, revocation of licenses, and thousands of tragedies for lawyers and political activists, the judicial system and the appointed leader of the regime still do not have confidence in all lawyers in political cases. Therefore, it must take matters into its own hands and put obedient groups, who are sometimes even more severe than the prosecutor, against the defendant. A political defendant in detention has two options: either to face interrogators and torturers alone, or with a lawyer who has been approved by the filtering system and is essentially aiding and abetting the torturers or approving their actions.

“The purpose of this article is for the authorities to make efforts and attempt to nullify the new law and some of its provisions that are in favor of the defendants. Secondly, to return the political defendants to the era of pre-reform, the era of absence or domination of lawyers. Independent lawyers either have to comply with the approval of the head of the judicial power, in which case they are no longer independent, or they are removed from the field of involvement in political cases where political, social, human rights, civil activists, etc. require their essential presence.”

The history of judicial encounters in the Islamic Republic is a history of violating the most fundamental human and civil principles. Even when political activists are supposed to feel safe, a clause brings everything back to square one.

And it seems once again the words of Asadollah Lajevardi, the prosecutor of the Black Decade, are echoing in my ears, who used to say about the defense of prisoners during those years: “In anti-revolutionary crimes, there is no motivation for lawyers to defend these gentlemen (referring to accused individuals of groups such as Mujahedin and Fedayeen). Because one must have a certain belief in armed movement against the system in order to take on the defense of a defendant and come and defend them.”

On that day and in the sixties, no one had the courage to defend the accused, as with this argument, it was possible for the lawyer to suffer the fate of his client. It seems that the same literature is still prevailing and our lawyers are still suffering from the same calamity. There is no trust in the lawyer, because the logic is that if a lawyer accepts someone’s case, then they have at least a minimum of shared opinion with their client! What a baseless argument. An argument that goes against the spirit of the main principle of lawyering and its legal foundations.

But if only there was a bit more independence in the judicial systems of some neighboring countries of Iran, such as Turkey or some Islamic countries like Malaysia, within the Iranian judicial system. On that day, perhaps the luck of political activists would have turned and maybe, just maybe, they would have felt a sense of security against the powerful and lawless security apparatus of the Islamic Republic from various institutions. But it seems that the air is still cold and the heads of independent activists and lawyers are still being held tightly in the grip of cowardly oppression in various fields.

For more information, you can refer to:

1- Lajvardi’s speeches on YouTube

2- La’jvardi’s return to the head of Evin Prison on the Iranian History website

Created By: Ali Kalaei

Created By: Ali KalaeiTags

Ali Kala'i Javid Tahmasebi Magazine number 51 Monireh Brothers Monthly Peace Line Magazine Mrs. Saberi Reza Alijani Taqi Rahmani ماهنامه خط صلح

![Ali-Kalei[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Ali-Kalei1.jpg)