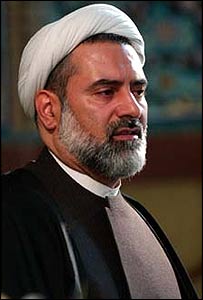

Women’s rights in Islam in conversation with Mohsen Kadivar

Dr. Mohsen Kadivar is a researcher, writer, religious thinker, and reformist political activist. After the February 1979 Revolution, he left his studies in engineering unfinished and began studying religious sciences in Shiraz in 1980. In the middle of Khordad 1360 (June 1981), he went to the seminary in Qom and is considered one of the students of Ayatollah Montazeri and the youngest Iranian religious scholar.

I had a conversation with Mohsen Kadivar about women’s rights from the perspective of Islam and also the differences between traditional juristic views and modern religious thinkers.

Mr. Kadiour believes that the meaning of freedom of dress is not “absolute freedom” and says: “There should be no common ground between different Islamic perspectives!”

Mr. Kadiour, does Islam have compatibility with what the free world and women’s rights activists consider as the rights of Muslim women, or does Islam have a special and different definition for “women’s rights”?

Firstly, in both sides of the issue, there is not as much clarity as is presented in the question. The rights of Muslim women in the free world and women’s rights activists are represented by a diverse spectrum of radical, moderate, and conservative views. Muslims are also divided into three groups in this regard: traditional conservatives, moderate extremists, and radical reformists. Each of these three groups also represents a spectrum.

Secondly, I can only compare my understanding of both concepts, considering that there are also other opinions from both sides. What is recognized in the moderate view of human rights and the rights of Muslim women is compatible with the moderate view of human rights among Muslims. In the book…

The rights of people.

(1387) I have discussed this topic in detail. It is sufficient to refer to its introduction.

Thirdly, all human rights are subject to not causing harm to others and not conflicting with public health, ethics, and safety. From an Islamic perspective, the exercise of rights for both men and women should not violate modesty and chastity. Islamic standards of modesty or chastity require limitations in the gaze and clothing of believing men and women. Modesty is a constant moral value in Islamic law. If this principle is observed, Islam has no problem with any of the rights of Muslim women as far as I understand.

On your personal website, we sometimes come across fatwas that do not differ much from the views of traditional authorities in that field. For example, regarding women’s clothing, you have forbidden women from wearing tight jeans and have not even considered the social norm in this regard. What is the reason for this strictness?

Firstly, there is no requirement for there to be any agreement between different Islamic perspectives. It is not the case that traditional authorities are always conservative and non-traditional ones are always liberal. In “Islamic Values and Laws,” traditional scholars who are conservative have similar views to moderate and extreme scholars. However, traditional authorities often consider the rulings of past jurists as established principles, while I, based on specific criteria that I have stated in my principles of jurisprudence, believe in much more time-sensitive and variable rulings than the traditional perspective. I also believe that many of the established religious rulings are based on the customs and norms of a specific time and place, rather than being absolute. However, it is clear that unlike radical reformists, I do not believe in a version of Islam without sharia, and as a result, I do not consider all jurisprudence to be incidental, variable, abrogated, and related to the past. Therefore, my religious stance falls between these

Secondly, the human rights system is not like democracy and secularism, which can replace religions, beliefs, schools of thought, and ideologies. According to the standards of human rights, democracy and secularism have the right to follow any religion or belief and to respect and recommend valid religious and ethical standards in their own religion and belief. In such a way that if someone is not practicing their religious teachings or is generally non-religious, in all three cases, it is a fundamental human right that no one can be forced or punished for their religious or non-religious beliefs and actions. If the declaration and recommendation of these religious and ethical standards are not accompanied by coercion and worldly punishment in case of violation, it cannot be considered a violation of human rights simply because some people do not agree with these standards.

Thirdly, even in the narrowest secular perspective where religion is considered a personal matter, the voluntary and free observance of religious teachings does not have any connection to human rights and should not be challenged or criticized.

Fourthly, a young girl has asked me about her religious duty regarding a specific type of clothing. I have also mentioned “without specifying any examples” the guidelines of Islamic dress according to my understanding. A believer who trusts the Islamic verdict of a mufti acknowledges their expertise in this matter, and someone who for any reason does not accept their opinion or fatwa is not obligated to follow it. Unless someone invites a non-believer to follow the mufti’s opinion!? It is not clear to me how this question relates to human rights. It is not intended for the “ideology of human rights” to replace Islamic law and the Jewish tradition.

Fifthly, it should be known that in a place where religious law has established values and obligatory rulings, the customs of society – even non-Muslim society – are not reliable. The instances where customs are referenced in the principles of jurisprudence have been carefully determined. Do you expect the values and established Islamic rulings to be subject to the dominant customs of non-Muslims?

Is the right to freedom of dress for women recognized in Islam? For example, according to the early history of Islam, is there any information about how the Prophet dealt with women who did not want to adhere to the accepted dress code after the revelation of the verse of hijab?

Your question has two parts. In response to the first part, I must say that the concept of “absolute freedom” of dress is not what is meant, as in all societies, there are certain limitations on the dress of citizens, both men and women. For example, in America, appearing naked in public is a crime. The minimum dress code in public varies in different cultures. On the other hand, no one can be forced to wear a specific uniform or use a specific color in their clothing.

Islam has considered modesty and chastity as a necessary introduction for both men and women believers (not just women), requiring a minimum level of covering. This minimum, in my understanding, for Muslim women is to cover from the neck to the knees in a way that the natural adornments of the body are covered. By observing this minimum, Muslim men and women are religiously entitled to a relative freedom of dress. This obligation is a religious obligation, not a legal or punishable obligation.

In any society, the minimum coverage depends on the legislator and the accepted culture. The minimum legal coverage should be less than the minimum religious coverage, so that, firstly, the freedom of believers is meaningful, and secondly, the rights of non-believing citizens are also respected. In any case, “

Compulsory hijab is devoid of valid religious justification.

(July 2012).

But regarding the second question: after the revelation of the verses about hijab, there is no evidence of disobedience and lack of observance of Muslim women from Islamic standards on one hand, and coercion and punishment of violators by the Prophet (PBUH), Imams (AS), or Caliphs on the other hand. Furthermore, my latest views on women’s hijab can be found in the series of articles “

A reflection on the issue of hijab.

(1391) is available for study.

Can a woman remain a Muslim without following the social and religious laws related to women, even if she does not want to?

This issue is not specific to women. Both men and women are subject to this ruling. It is a practical aspect of Islam. A Muslim is someone who, firstly, believes in Islamic beliefs, secondly, does not deny practical rulings and obligations of prophethood, and at least performs some of the rituals and acts of worship of Islam, and thirdly, does not neglect some of their religious duties. Even if they do not fulfill some of their religious obligations, they are still considered Muslim. And since they have not explicitly or practically denied the two testimonies, no one has the right to consider them non-Muslim.

In other words, there are two types of Muslims: first, the active Muslim who is called a believer, and second, the neglectful Muslim who does not fulfill certain religious duties. If a Muslim neglects certain religious obligations, it is acceptable only if they are an expert in religious sciences. Otherwise, their excuse for neglect is only valid if it is justified by a religious scholar (mujtahid) as a valid reason for neglecting that religious duty.

Should human rights be limited and restricted within the framework of Sharia laws in the eyes of a faithful Muslim, or vice versa?

Firstly, ten years ago in the writing “

Human rights and religious enlightenment

(Sun, summer 1382, and then the book “Human Rights”, 1387) In detail, I have argued for the precedence of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights over the dominant understanding of the Sharia (traditional Islam). The reason for this precedence is the rationality, fairness, morality, and effectiveness of the principles mentioned in the declaration compared to some past fatwas that have been repeated without new reasoning in different circumstances and beyond the initial context.

Secondly, if we consider the values of morality as the basis of the law (not the legal system), then it is clear that for a faithful Muslim, the adherence to these fixed moral values is not negotiable and their acceptance of human rights cannot contradict these fixed moral values. This is my perspective on the law. It is clear that the discussion is about the rights of Muslim humans, meaning the cases that are recognized as valid international documents, not everything that is introduced as human rights without a valid international document.

Mr. Kadyor, as a man, does he have the right in Islam to determine the type of clothing and behavior of his wife?

A marriage contract has rights and responsibilities for both parties, if no conditional clause is included in the contract, the couple cannot expect more than their religious rights from each other.

B. Islamic rights (to the extent of my understanding) have not given any specific right to men in this matter, although it has set responsibilities for both spouses in this regard. In other words, a husband does not have authority over his wife to determine her fate without her consent and free will.

The minimum requirements for the coverage and interactions of a married person are religious matters that cannot be increased or decreased by the man or woman. The religious beliefs and level of commitment of each couple determine these minimum requirements.

As a Muslim, husband and wife can use the obligation of enjoining good and forbidding evil, just like other Muslims, towards their life partner. However, fulfilling this obligation is different from the mutual rights and responsibilities of marriage.

It is clear that married life requires mutual understanding and agreement, regardless of legal requirements.

And in conclusion, what is the difference between the fundamental principles of traditional jurisprudence and the religious jurisprudence of modern thinkers like you?

Firstly, traditional jurisprudence has confined itself to “ijtihad in branches”. The epistemological foundations of this type of ijtihad are world-view, epistemology, anthropology, and theology, which have not been subject to “critical reinterpretation”. In this approach, the Quran is the “book of law” and the Sharia is the “legal system”, and the book and tradition “extracted from history” are referenced. The right of reason in ijtihad has not been practically observed and the ethical and just nature of fatwas has not been the concern of the jurist’s inference.

Secondly, my understanding is based on “ijtihad in principles and fundamentals”. “Ijtihad in principles” means using ijtihad in the principles of ontology, epistemology, anthropology, and theology, and paying attention to the achievements of moral philosophy, legal philosophy, political philosophy, and overall sciences related to the subject of religious rulings. “Ijtihad in fundamentals” means using ijtihad in the fundamentals of jurisprudence, such as paying attention to the principles of hermeneutics, taking a “historical perspective” on the text, re-reading the text in its context, viewing the Quran as a “book of guidance” (not a book of law), viewing Sharia as “moral values” (not a legal system), and adhering to the four principles of being rational, just, moral, and more effective than rival solutions in the process of deducing religious rulings.

Thank you for the opportunity you have given us.