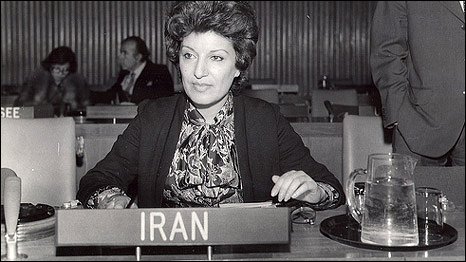

Mahnaz Afkhami: Emphasis should be on a society with justice and fairness.

Mahnaz Afkhami was the head of the Women’s Organization during the Pahlavi era and the Minister of Women’s Affairs in the last three years of that period.

Mahnaz Afkhami, who has a high level of education from reputable universities outside of Iran, is a living example of the elite generation that emerged during the Pahlavi era and laid the groundwork for many modern and progressive activities in Iran before the January 1979 revolution. With the inevitable downfall of the Pahlavi monarchy, she left Iran. Currently, Ms. Afkhami is the head of an active non-governmental international organization in the field of education and women’s rights, called the “International Organization for Education and Cooperation of Women,” with its headquarters located in the United States. She is also the founder of this organization.

I had a detailed conversation with Mahnaz Afkhami on the sidelines of a conference in New York on “Women in Leadership and Decision-Making Roles”. We asked her to tell us a little more about herself and how she became the second female minister in Iran.

He believes that beyond individual successes and progress in a specific field, the emphasis should be on pioneering leadership and creating a society with justice and fairness.

You are the second female minister of Iran, after Mrs. “Farrokhro Parsa”. How did this happen and what process did you go through? How did Mahnaz Afkhami choose this path?

From January 1, 1976, I was appointed as the Minister of Women’s Affairs and this was the first time that someone was appointed to such a position in Iran and the entire region; of course, now there are about 100 people in the world who hold a similar position, but at that time it was not very common and as a result, because it was a new and innovative effort towards equality, it provided the opportunity to present new ideas and establish a new framework for work in order to create conditions in the government where we could work better on women’s issues and we took full advantage of this opportunity to the best of our abilities.

Mrs. Farokhro Parsa was the Minister of Education and the first woman to serve in the cabinet. She was a role model for me and when I joined the Women’s Organization as Secretary-General, the issue of a Ministry for Women was brought up. She showed great kindness and welcomed me to work in the field of women’s rights at a national level. In a conversation I had with Mrs. Parsa, I made some requests. As she was in the cabinet at the time, I asked her to collaborate with the Women’s Organization in promoting education for women on a larger scale and to take steps towards changing the textbooks and the role of women in them. In those textbooks, especially in the first few years of elementary school, women were always portrayed in a very traditional and limited role; for example, women were seen with an apron in the kitchen while men came home with a briefcase from work, or a girl would throw a ball up a tree and when it got

Please tell us a little about yourself, your education, and who has been your biggest motivator in your family or outside of it.

I was born into a family that was involved in agriculture (especially my father and my paternal family), but they were relatively well-off. My mother, however, came from a wealthy family and was more focused on academic work, writing, and research. She was one of the first women to attend university and my grandmother was also one of the first women in Kerman (where I was also born) to have her own job as a seamstress and manage her own life, despite being divorced from her husband. Both sides of the family had strong and independent women, and for example, it was not a problem for the women in the family to take on the role of managing inherited land or agricultural resources. As a result, my parents always believed that my sister, brother, and I should pursue higher education. I studied in high school in America and my major was English literature. After returning to Iran, I taught English literature at the national university and became very familiar with the issues facing young girls

In any case, after the conversations we had with these girls, we decided to form a student girls’ association and always organized lectures in it and invited people with opinions to speak, and the girls themselves were constantly discussing and exchanging ideas. The members of this association quickly expanded to 400 people, and this gradually led me to become more involved in women’s activities and join the Women’s Organization. My joining the Women’s Organization was also through getting to know the Shah’s daughter, Ashraf Pahlavi, who was then the head of the Women’s Organization and also the head of Iran’s delegation to the United Nations.

I asked, why is the discourse of successful Iranian women who hold key roles in society important and what message does it ultimately want to convey to society?

In my opinion, this has two aspects; first, that women, who make up more than half of the world’s population, should have their voices heard and play the role they should in decision-making. Second, the way women face issues and how they manage and lead has recently changed and is generally different from what we are used to. It is good that this management style, which I am not saying all women have, but it seems that most of them do, is utilized and we can benefit from this great force. Regarding the success of women, aside from individual achievements and progress in a specific field, my emphasis is more on the perspective that a woman can have and be a pioneering leader; what she wants, why she wants to take on leadership, what she wants to do, and what impact she wants to have in shaping society and how she can create a fair and just society.

Your discussions lead me to this question: How much can society and environmental conditions contribute to the success of a woman, like yourself, in fulfilling her role?

Well, in many societies, there is a huge difference between classes, or the facilities available to those who are from a wealthier class are not comparable to those who are poor. In America itself, one of the fundamental issues currently, unlike what existed in the past, is that the difference between the highest level and the top one percent, who, of course, some of them are in the middle class but a considerable number of them are practically poor, is very high; so that the top one percent can provide all kinds of facilities for their children and send them to any school or university. Those who come from poorer classes and their number is also very high, for example, are in a situation where their parents are not together at all or if they are, they do not have enough facilities and literacy to provide an effective culture for their children. But well, all the importance of female leadership and leadership that seeks justice is in trying to increase these awareness and facilities at the societal level so that

We should not equate the successes of individuals, namely women, and even a significant number of women, with what society makes available. When you look at the relationship between the individual, society, and government in Iran, you see that Iranian women are living under extraordinary difficult conditions. Various forms of sexual apartheid and restrictions, such as segregation in public spaces, the inability to travel freely, and even the right to choose one’s field of study – which has certainly improved compared to before – have made Iran one of the most backward countries in terms of upholding basic rights that a woman, as a human being, needs. This is why the situation is not easy, but the Iranian people are incredibly intelligent, curious, and hardworking, with a great history of striving, and have always wanted to learn from and teach others; for example, while the laws in Saudi Arabia and Iran may be the same regarding women, an Iranian woman is not the same as a Saudi Arabian woman. In the worst

Can Iranian women who are successful outside of the country be considered as suitable role models for Iranian women within the country, given the deep social differences and opportunities available in predominantly Western societies compared to the limitations and restrictions faced by women within the country?

100%, see for example our organization, which is the International Organization for Education and Cooperation of Women. For years, we have been producing educational materials for participatory management and leadership and publishing them in twenty languages, with Persian always at the forefront of the languages we work with. If Iranian women were able to participate in these workshops through the internet or in person, they would be incredibly creative and do a great job.

Another important point is that the issue is not about having a group of women take on management and leadership roles, but rather the type of management and leadership that matters. It is possible through creative teamwork, not individual achievements.

It seems that one of the problems of Iranian society, both before and after the 1957 revolution, is the balance of power between conservative and progressive forces. The first bill to support families was presented to the parliament in 1946 and was passed with amendments in 1953. However, even before that, lawyer Ms. Mehrangiz Manouchehrian, along with 19 other female senators, had proposed a bill to abolish polygamy. What happened to the fate of this proposed bill by Ms. Manouchehrian?

Mrs. Manouchehrian was an extraordinary intelligent, dedicated and top-notch lawyer. She did a great job in preparing this bill and sparked interest in others for this issue. But you see, the issue of rights is very complicated and the most conservative groups working in any government deal with legal issues and bills. It is generally a slow and conservative field that always wants the most, but you can’t always get the most. Mrs. Manouchehrian wanted to take a few women (of course all the enlightened women of Iran wanted this to happen), but you have to convince others as well and society is not always ready. It needs to be discussed, tested, until what one desires can gradually be achieved at a time when society is more prepared.

Well, a few years later, when Ms. Mehrangiz Dolatshahi brought a revised bill, it was accepted. A few years later, when I was working for the Women’s Organization, we worked on revising that law and were able to achieve many things, including limiting polygamy to two wives and only with the permission of the first wife, although this was not everything we wanted; we wanted polygamy to be completely abolished, but in those circumstances, this was the most we could achieve. If there had not been a revolution and everything had not gone this way, the next thing would have been that multiple women would have been completely eliminated; but keep in mind that except for Tunisia at that time, there was no restriction on polygamy in any Islamic country…

Apart from limiting polygamy to a second wife under the conditions I mentioned, the issue of child custody was also important. In the previous law, custody of the child was transferred to the paternal grandfather or the father’s family after the husband’s death. The issue of paying child support for the husband after divorce was initially such that the husband could pay for two months but then refuse to pay and the process would have to continue with court proceedings and the judge’s opinion, making it very difficult and almost impossible for women with less financial means. However, the next bill and its executive regulations were such that if the judge had made a decision once, they could enforce the same ruling in subsequent cases. Another issue was about women’s work. Women were required to get their husband’s permission. We tried very hard to eliminate this requirement, but it was not possible. The Ministry of Justice was not willing to back down on this issue. For example, it was said that a woman might decide to become

In your opinion, why do you think there was no immediate resistance against the cancellation of the Family Protection Law after the 1957 revolution? Do you believe the reason for women’s lack of resistance against the cancellation of the law was due to the societal belief that these reforms were imposed from above and women’s masses were not organized in independent organizations to support such a law?

These are myths that we ourselves have told, and now for various political reasons, we have taken away our sense of self-sufficiency and our sense of the importance of our vote and our own actions, and denied our own power. While all of these movements that have taken place at different stages for Iran have involved the involvement of the masses. Of course, by masses, I do not mean all the people in all the villages or all the corners of the country. Those who do not have access to communication facilities cannot play a determining role in these matters – at least not at the beginning. Usually, movements that lead to a political outcome are taken up by the middle class and a group of intellectuals. The same was true for the issue of education; it is true that Reza Shah played a significant role in putting his power behind this issue, but it was not possible without women wanting it and pursuing it. Or in the case of the stages of women’s suffrage, women made efforts

You may have attributed many of the achievements that women themselves had achieved during this period, and some of which were taboo in society, to the struggle against conservative forces towards the royal family. This may have caused a kind of rift between the women’s organization and the mass of women who were sometimes opposed to the royal family. How do you view this issue today?

The movements related to women were never comparable to what we see in the Third World, even today. One million people were working with the Women’s Organization every year. Every woman, from Mrs. Manouchehrian to female lawyers, journalists, and poets, all collaborated with the Women’s Organization. This means that almost no one in Iran refused to lend a helping hand and cooperate. However, there were groups that were active outside of Iran and were not willing to value or acknowledge anything that was happening in Iran. Regarding the Family Protection Bill, even years after the revolution, we had many discussions with friends who were involved in anti-government activities abroad, until they finally agreed to come and see for themselves the progress that had been made in this area compared to other countries.

Based on your experiences in the field of working on women’s issues in Iran and internationally, if you were to identify three weaknesses that we should work towards improving in Iranian society, what would those three weaknesses be?

The most important issue regarding women is legal and legislative restrictions, and unfortunately, despite decades of effort, women have not been able to work in this field, even during the presidency of Mr. Khatami, when it seemed that reforms were underway. After two terms of hard work, he was unable to even change the legal age for marriage to an acceptable age. Unfortunately, the major issues are legal and legislative, and this is also related to the religious foundation chosen for governing the country. It is not a simple matter and I cannot imagine that without changing the constitution and without a general review of the constitutional foundation, the situation of women can be significantly improved. In almost every field where equality or participation is mentioned, there is a legal barrier that has not yet been overcome. If there have been any changes, they have been small. The issue of buying back all government employees was also on the agenda, and the issue of academic majors that were closed to women has also made some progress, but

The second and third issue is that we return to a culture of social participation and a healthy culture of giving and taking in politics; far from slogans, myths, and creating heroes or villains. This means creating a sense of responsibility in society among individuals so that they see themselves as responsible citizens and make fair judgments. This issue must become a social culture, because each individual in society must accept this culture in order for us to implement it in society. I believe we have the intelligence and talent to handle this, and the main issue is that amending the constitution is necessary.

Do you, as a successful Iranian woman, feel responsible for empowering women within the country, either individually or organizationally? If so, please provide a brief description of its goals, actions, and impacts.

Well, the organizational work that I am currently involved in is related to this. We have both online courses and textbooks in Persian. These educational classes and books have been prepared in various fields, including management, political leadership, horizontal leadership, combating violence against women, how to use technology to equip and educate people in Persian. These have been tested and implemented and are accessible to individuals. Of course, in some specific courses, it is more possible to do this inside Iran, and in some courses, it is much less possible. One of the important things is that fortunately, there is a lot of exchange between Iran and outside of Iran, and what is learned outside is transferred inside as well. Groups working outside are always prepared to use these inside, and hopefully, if the space becomes more open, it will be very helpful to be able to work more widely inside.