Group of activists with ten years of experience in sustainability and collective work/ Ali Kalaei

“From the ashes of every great event, something is born that may continue to evolve. The phoenix is born from its own ashes; each time, this new phoenix may take on a different form, but the continuation and evolution of the same story that existed yesterday and has now emerged in a new form today.”

Years ago, during a time when the candle of the reform government was about to go out and the fear and hope of the early days after the June 76 revolution turned into the autumn of a new structure of government and the complete closure of the space, a group of young people rose up and started a movement that continues to this day. In the final days of the reform government, a generation was raised with all its weaknesses and strengths, who had learned and believed in civil society, civility, and modernity. A movement began that ultimately led to the sitting of Ahmadinejad on the throne in the month of Esfand, and he was referred to as the president, even though many did not believe in his leadership. This movement aimed to promote human rights and expose the blatant and hidden violations of human rights in Iran. Despite all the hardships and conflicts, this movement continues to this day and has achieved remarkable success compared to other non-governmental and independent organizations in Iran.

“این تصویر نشان می دهد که یک زن جوان در حال خواندن کتابی در حیاط خانه است”

This image shows a young woman reading a book in the courtyard of a house.

Street Activities of Volunteer Forces Collection – 1388 – Photo from the Archive of Human Rights Activists in Iran.

The years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency were a test for independent civil institutions in Iran. Many were forcibly shut down by the regime’s security forces. Others voluntarily closed their doors due to the oppressive security environment. Some also abandoned their work and left their newly established institutions alone and abandoned, seeking other opportunities. However, there were a few independent civil institutions that stood against the anti-civil wave that had gained new life with the new government. Despite the constant pressure and occasional confrontations with the regime’s security forces, they insisted on transparency and continuing their work in a civil manner.

In those years, independent human rights institutions were present at the national level. However, from the writer’s perspective, three of these institutions stood out and had a more prominent presence in Iranian civil society. The “Association of Human Rights Defenders,” which has been and still is an association of elites, but according to the writer, despite its valuable human and specialized resources, lacked connection with the lower layers of Iranian society. The “Human Rights Reporters Committee,” which initially was a student committee and later, after its members graduated and based on the principle of honesty with the people, took off its student title, was also a human rights institution that, despite its lack of members, provided many services to promote the discourse of human rights and spread news of human rights violations in Iran. The “Iranian Human Rights Activists Group,” which, with its expansion, had become one of the most influential human rights institutions in Iran (alongside the two aforementioned institutions and others). These three institutions, alongside

“این عکس یک منظره زیبا از کوهستان است”

This picture is a beautiful landscape of the mountains.

Shahin Najafi expresses his support for this institution by wearing the t-shirt of the activists’ collection – 1389 – Photo from the archive of human rights activists in Iran.

Undoubtedly, the presence of organizations and other influential institutions such as the “Association for the Defense of Prisoners’ Rights”, of which our esteemed professor Mr. Emad al-Din Baghi was one of the founders, the Committee for the Follow-up of Arbitrary Detentions, the Commission for Human Rights, and other human rights organizations and independent institutions in Iran, cannot be forgotten. However, despite their serious presence in the field of assisting prisoners, both politically and non-politically, they have violated their rights, either fully or to a lesser extent, in terms of news and information dissemination. It is this characteristic of being a voice for the voiceless that distinguishes the human rights activists in Iran and the Human Rights Reporters Committee from other groups and organizations.

With one year left until the 88 elections and the rise of public mobilization, it seems that both groups of activists and the reporting committee have come to the conclusion that transparency should be their main focus. Therefore, both groups took action to publish the names of their members in the virtual space; with the aim of promoting transparency in a human rights institution and preventing any misuse by individuals under the name of these two well-known and widespread groups.

But none of us, neither the friends of the human rights activists nor people like me who were serving on the Human Rights Reporters Committee, could have even guessed the severity of the 88 hurricane, when the demon of tyranny would come and swallow up all the activists, with massacres and destruction, whose names have been published.

They ask Mr. Banisadr if it is true that the revolution is eating its own children? And he, who is the first president of Iran, says that we were not eaten by the revolution. We were eaten by Mr. Khomeini!

Human rights groups and independent civil institutions that resisted during the years 1984 to 1988 can be considered as the founders of the 1988 uprising in Iran. The discourse that had spread in Iran in this regard was the result of the efforts of these young people who stood tall day and night, despite threats and scattered and occasional attacks by the security forces of the theocratic regime, and remained committed to their human rights duties. In fact, in an analytical view, a part of the preparation of the social body for an uprising (which was consciously present in the general body but unconsciously in the leadership and elites) should be attributed to the efforts of these independent human rights organizations and the youth who, by publishing news of blatant and hidden human rights violations in Iran and becoming the voice of the voiceless in society, had made people aware of what was truly happening and the underlying issues.

This is a picture of a beautiful flower.

The winners’ plaques and coins of the 1378 Blogging Competition – Photo from the archive of the human rights activists in Iran.

These institutions were so insistent on their ideals that they first started with themselves in order to promote transparency in the social and civil sphere, and by publishing the names of their activists, they became a model for transparency in the public and civil society.

It may be necessary to explain a little more about this impact here. If we consider the 88 uprising in the context of Hadi Saber’s approach, one of the historical moments of freedom, equality, and brotherhood in Iran, in a modeling, we can refer to two ascending and descending curves for this uprising and a peak point on the curve. In the ascending curve, between the previous and current peaks, social, civil, and democratic forces, advocates of human rights, equality, and brotherhood are in a minority position compared to the body of society. But by preserving the torch and the ideal and moving the society and educating it towards the point of liberation, they lead the peak of this process forward. These efforts, despite sometimes being scattered, turn the potential energy accumulated in the ascending curve into kinetic energy and from the peak point, the event (in this case, the 88 elections) descends on its own and suddenly brings a flood of events with it. In the

The mentioned organizations and institutions of human rights are one or more groups of carriers of that stone that are supposed to be led towards the peak of justice by them, in order to make a change in the descending path of society. If it is said that the group of activists, reporters’ committee, or the like were effective in the background of the 88 uprising, it is with this analysis and for this reason.

But the general uprising of the people in 1988 and the subsequent attack of the entire system of the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist on the existence and non-existence of Iranian society tried to break the integrity of these human rights institutions. In fact, if these organizations and human rights institutions were subjected to beatings, confrontations, pursuit, torture, imprisonment, and a thousand and one tragedies after the 1988 uprising, it was not because they were weakened and vulnerable after the rapid events of 1988, but because the demon of tyranny was trying to silence the groups that he felt were spreading civil and rational discourse and human rights in Iranian society. His goal was to silence them and suppress the entire uprising, which was on the verge of becoming a movement. In fact, the broad and extensive security apparatus tried to swallow and destroy these groups. But the victory was not for the security apparatus, but for these human rights groups.

“این عکس یک منظره زیبا از کوهستان است که در آن آسمان آبی و ابرهای سفید به تاریکی کوهها میچسبند.”

“This photo is a beautiful landscape of mountains where the blue sky and white clouds cling to the darkness of the mountains.”

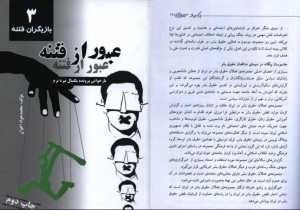

A group of activists targeted and accused by the security apparatus: A middle page and the cover of the book “Crossing the Sedition: A Re-reading of One Year of Soft War” published by the Student Basij in Iran – 1390.

In Esfand 88 (February/March 2010), there was a time when in the course of encounters with all civil activists in all fields, the patience of the security forces of the coup regime finally ran out and with a massive and widespread crackdown, they arrested all those who were associated or members of the group, whose names had been published from the leader to the members in the organizational chart of the group. In fact, here the coup regime is taking advantage of the transparency of the human rights activist group and using it as an excuse to arrest all of its members. This arrest is actually a security and forceful measure to disable the group and prevent its activities. However, this attempt failed and the security forces were defeated by the force of honesty, determination, and perseverance of the human rights activist group in Iran.

After that blow, although the transparency of announcing the names of activists no longer exists and the possibility of such a thing is not available, and perhaps in a general critique, the publication of names by the two groups affected by the 88 strike (the group of activists and the reporting committee) was premature and based on a summary of the current situation, but the work of the human rights activists, despite all the irregularities, disrespect and tragedies such as the loss of the late editor of Harana, the late Seyed Jamal Hosseini, continues with full strength and steadfastness.

Perhaps in general, a few issues can be considered as strengths of this collection. Of course, not all issues mentioned are unique and the points raised have come to the mind of the writer. Perhaps if another person wrote this, other points would also be mentioned by them.

The most prominent strength of the activists’ group, according to the writer’s belief, is its ten-year continuity. The collective work experience among Iranians has shown that standing and working together for ten years, with the Iranian mind, land, and conscience, is a very significant event and remains something similar to a miracle. The individualistic traits of Iranians and our lack of compatibility with collective work are not hidden. From historical, cultural, and psychological criticisms of Iranian society, from Seyed Ali Jamālzādeh to Mehdi Bāzargān and Hassan Narāqi, to efforts to criticize the collective work mentality in Iran by Tāqi Rahmāni (whose compiled sessions in the virtual community with Malaysian activists), all have tried to trace and understand this trait and negativity and lack of collectivism in Iranian collective work and to understand why in other countries, in the West and East of the world, people come together in a collective work and by gathering and empowering collective forces

Another important point is the common value of this collection and only one or two similar collections (which unfortunately have often been stopped at some point in time and continue to exist in a frozen state) is the voice of the voiceless. The human rights activists in Iran have been able to have a presence and influence in both prisons and remote areas, despite being far from the center and communication, and be the voice of those who previously had no voice. Although this ability has been somewhat reduced by the expansion of ethnocentric media (which is also the result of heavy security pressure on the activists and the connection of ethnocentric media with the local people in that specific region), the credibility and efforts of this collection to maintain these connections and preserve the principle of being the voice of the voiceless continues. This principle is one of the main reasons for the anger of the Iranian government towards this collection and similar groups in recent years.

One of the characteristics of this group is its structure and organization. Although this structure and organization may sometimes suffer from bureaucratic diseases, it provides a commendable order that can move forward in a creative (not mechanical) system. The experience of traditional collective work in Iran is a council. One person is the mediator and center of the council, and they are the first and final decision maker, while the rest, without any hierarchy, participate in whatever task is at hand (not necessarily what they are obligated to do or capable of doing). This bureaucratic disease (which was effective in pre-modern times in Iran and is still used in traditional councils today) becomes a violation of its own purpose in modern organizations and institutions, sometimes leading to dangerous internal conflicts, collapse, or freezing of the relevant institution or organization. This means that one person, thinking of themselves as the founder of the council (institution), issues a decree that either must be followed or results in conflict (in a situation where there is no structured

“متن راست چین”

“Right-aligned text”

The tomb of Seyyed Jamal Hosseini – city of Nusaybin, Turkey – photo from the archive of the Human Rights Activists Collection in Iran.

It has been ten years that the human rights activists have continued their work. Along this path, the security forces of the Islamic Republic have repeatedly accused them of baseless charges. From associating them with certain political groups to trying to destroy the moral reputation of these active forces. Unfortunately, not only the loyal security forces, but also some hasty friends have been and are involved in this path. However, the performance of this group – with all the mistakes it has certainly made and continues to make – is not only defensible, but also commendable, as it is in accordance with a rule that has no wrong unwritten dictate, and the dictate that you have written and the work that you have done is certainly wrong and mistaken. The expansion that this group has created for itself, not only in its own media and its own theory (with the monthly magazine of Khat-e-Solh) but also at other levels of the Fourth Pillar Committee, and its efforts to combat filtering,

It has been ten years since the establishment of this organization. We hope that in another ten years, this organization will still stand strong and continue to be dynamic and creative, and that it will be able to celebrate the 20th anniversary of this youth institution for human and civil rights in Iran. May that day be a sign of less heavy-handed security measures and may this organization and others serve as supporters for the expansion of the discourse of democracy and civil society in Iran, allowing for the presence and all-encompassing activism to thrive.

Created By: Ali Kalaei

Created By: Ali KalaeiTags

Ali Kala'i Monthly Peace Line Magazine Population work The human rights activists group in Iran.