Child Labor in Iran: The Silent Outcry for Social Justice/ Hossein Yazdi

The phenomenon of child labor in Iran serves as a full-length mirror reflecting entrenched economic injustice, educational inequality, and foundational flaws in social policymaking. Drawing on official statistics, global reports, and reputable research, this article demonstrates how institutionalized poverty, forced migration, and ineffective protective legislation push children into the hidden labor market. This process not only violates the fundamental rights of children but also entrenches class disparities and endangers social stability. The goal is to deeply examine the issue, explore its causes and consequences, and offer practical, sustainable solutions for achieving social justice.

Introduction

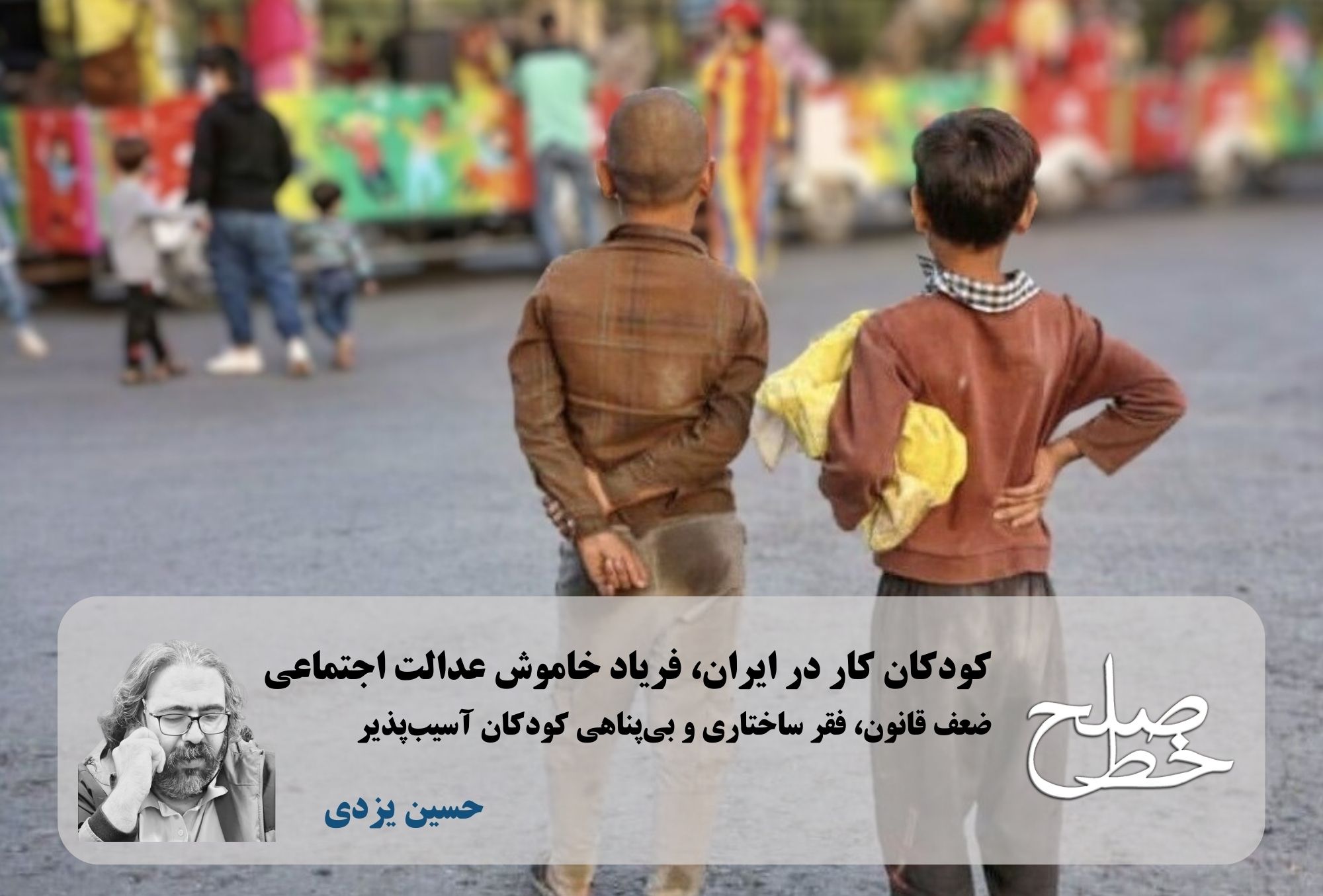

In the back alleys of Iran’s major cities, working children—tired-faced with small hands—paint a bitter portrait of profound social divides. These children are direct victims of ineffective economic policies, relentless inflation, and the unequal distribution of opportunities. Each day that this issue is overlooked, a new generation becomes ensnared in the trap of poverty and deprivation. Child laborers are not only the muted whispers of justice but also a warning bell signaling the collapse of social cohesion and the rise of class tensions.

Methodology

This research is based on secondary data analysis. Information has been drawn from official sources such as the State Welfare Organization (1) and the Statistical Center of Iran (2), international reports from UNICEF (3, 4, 5) and the International Labour Organization (6, 7), as well as academic studies. Key indicators—including poverty rates, school dropout figures, and internal/external migration data—have been analyzed to reveal the connection between these factors and the intensification of class inequality.

Root Causes of Child Labor Growth

A) Structural Poverty and Livelihood Crisis

Inflation exceeding 40% in recent years, coupled with widespread parental unemployment, has forced families to exploit their children’s labor. This further entrenches the cycle of poverty and transforms today’s child into tomorrow’s unskilled laborer. (2)

B) Inequality in Access to Education

Unequal access to quality education deepens class divides. While children from affluent families enjoy superior educational resources, those from lower-income households are often deprived of schooling before the age of fifteen.

C) Migration and Vulnerable Children

Migration from rural to urban areas and the influx of foreign nationals, particularly from Afghanistan, leave children defenseless against exploitation. Over 80% of street-working children in Tehran are non-Iranian and lack legal protection. (1)

D) Legal and Supervisory Gaps

Article 79 of Iran’s Labor Law prohibits the employment of children under 15. However, its enforcement is weak and selective. Family-run workshops and the informal sector are exempt from this law and are largely unregulated. (6)

Alarming Statistics and Realities

According to the State Welfare Organization (1403/2024–2025), 12,663 active child labor cases have been registered, with 60% being Iranian and 40% foreign nationals. (1)

In Tehran, over 70,000 child laborers have been identified, 80% of whom are non-Iranian. (1)

Unofficial estimates suggest between 1.6 and 2 million child laborers nationwide, marking a 9.6% increase over the past decade. (7)

Nearly one million children dropped out of school in 1404 (2025), the majority due to the need to work. (2)

These figures reveal not only a humanitarian disaster but also sound an alarm over looming social fragmentation.

Long-Term Consequences

Physical and Psychological Harm: Working children are exposed to long hours, toxic substances, street violence, and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.

Persistent Class Inequality: Deprivation of education condemns these children to low-value jobs in adulthood, perpetuating generational poverty.

Erosion of Social Capital: Early exposure to discrimination erodes public trust and lays the groundwork for social unrest.

Practical and Immediate Solutions

A) Targeted Livelihood Support: From Temporary Aid to Economic Stability

Targeted economic support is one of the most effective ways to prevent children from entering the labor market. Structural poverty—driven by over 40% inflation and parental unemployment—forces families to exploit child labor. (2) A practical solution is to allocate direct subsidies to at-risk families, not as temporary handouts but linked to employment programs for parents.

For example, UNICEF’s model in Iran since 2019 emphasizes “case management”: early identification of vulnerable families, economic status registration, and referral to social services for empowerment. (5) The main challenge remains corruption in subsidy distribution and insufficient coverage (only 40% of the social budget reaches impoverished families). The proposed solution is to create a national database to track households, monitored independently by NGOs, ensuring a minimum standard of dignified living and liberating children from labor.

B) Inclusive and Flexible Education: A Bridge Toward Equal Opportunity

Educational inequality deprives children from lower-income classes of schooling beyond age fifteen, pushing them into cheap labor markets. (3) Part-time education programs and flexible schooling must be implemented in underserved areas, such as the urban margins of Tehran. A successful example is UNICEF’s 2019 initiative in Jordan, which educated minority children and reintegrated them into the formal school system.

A similar model in Iran could integrate vocational training (e.g., digital skills) for child laborers to break the poverty cycle. The challenge is the 1 million school dropouts reported in 1404 (2025), (2) largely due to forced labor. A recommended solution is government investment in “alternative education” programs supported by the International Labour Organization (ILO), with conditional scholarships that prohibit child labor. This approach not only compensates for deprivation but also strengthens human capital for a more equitable future.

C) Rigorous Enforcement of Laws: From Paper to Practice

Article 79 of Iran’s Labor Law prohibits the employment of those under 15, but its weak and selective enforcement perpetuates exploitation. Over 15 organizations (including ministries of labor, education, and municipalities) are involved, but lack of coordination has caused 32 separate “child collection” campaigns to fail. (3)

A practical solution is to establish independent monitoring units with international participation (e.g., the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child) and impose strict penalties on violating employers. One alignment measure is with ILO Convention No. 138 on the minimum working age, which prohibits hazardous work under age 18. (6)

The main challenge is the inconsistency between domestic laws and international standards (e.g., the definition of “child” based on Islamic maturity). The solution is to withdraw Iran’s reservations to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1994) and train judges for uncompromising implementation to eradicate exploitation.

D) Protection for Migrant Children: Solidarity Beyond Borders

Over 80% of street-working children in Tehran are migrants (mainly Afghan) and lack legal protection. (1) Forced migration turns children into modern slaves, and national discrimination restricts their access to education and healthcare.

A proposed solution is to guarantee equal rights through integrated programs modeled after UNICEF’s initiatives for minority children. (5) The challenge is the economic crisis (including sanctions), which has made migrant families even more vulnerable. A practical response is to collaborate with international organizations to establish gender- and age-sensitive support centers, along with health and education insurance. This not only upholds human rights but also strengthens social solidarity.

E) Civil Society Engagement: The Driving Force for Change

Civil society—from NGOs to the media—must play a key role in raising awareness and pressuring policymakers. NGOs in Iran have managed to return 3–4% of working children to school, but government restrictions limit their broader impact. (3)

A proposed solution is to strengthen labor unions and civil movements to monitor child labor programs, inspired by international models such as UNICEF’s violence prevention initiatives. (4) The main challenge is the suppression of activists (e.g., labor protests). A viable solution is to apply international pressure through human rights reporting and financial support to NGOs for local programs. This grassroots participation can drive change from the bottom up and sustain justice.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of child labor in Iran stems from dysfunctional policies, institutional injustice, and neglect of children’s rights. It is not only a humanitarian crisis but also a threat to peace and social sustainability. Only through fundamental reforms, rigorous enforcement of laws, structural coordination, and active civil society participation can we dismantle the cycle of inequality and shape a just future for the next generation. The time for action has come—to turn the muted voices of these children into a powerful call for social justice.

.

.

Tags

Child labor Class division Discrimination Hossein Yazdi Inequality Layers of sediment Social justice Social stratification Unemployment ماهنامه خط صلح