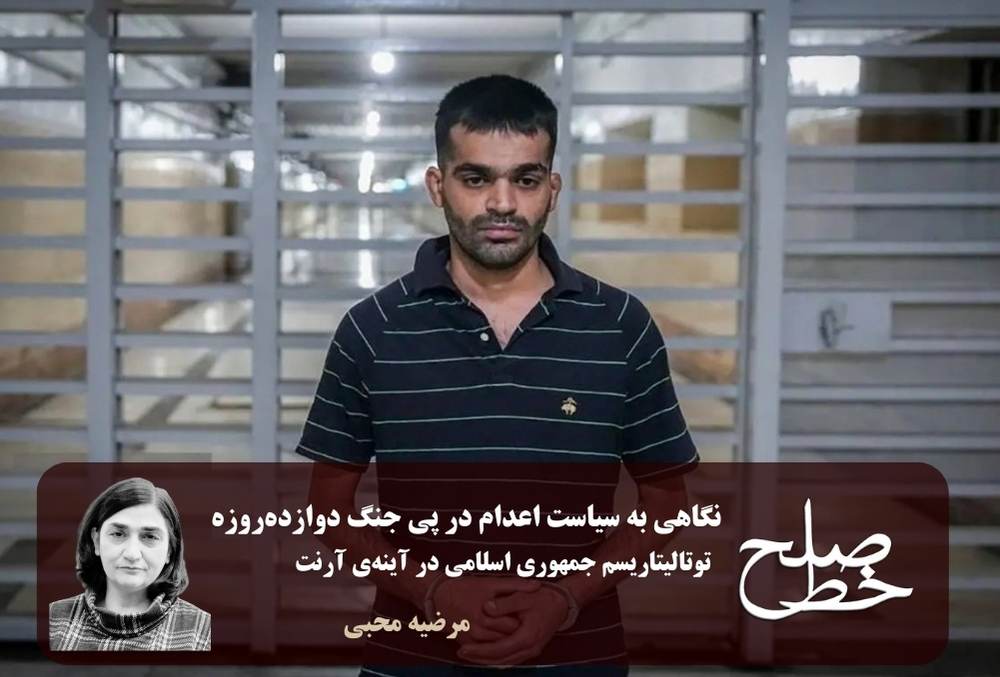

A look at the execution policy following the twelve-day war / Marzieh Mohabi

The 12-day war between Iran and Israel was one of the most intense military conflicts in the region in recent decades and marked the end of a dream for the leaders of the Islamic Republic to eliminate Israel from existence. This conflict began with Israel’s surprise attacks on nuclear facilities, military bases, and the assassination of high-ranking officers of the Revolutionary Guards, army, and nuclear scientists in an attempt to prevent Iran’s nuclear program. It continued with Iran’s missile and drone responses, leading to a worsening of the economic and social instability in the country.

In the past few days, the Iranian government has lost its atomic power plants – which had swallowed billions of dollars of the country’s budget and had turned into fortresses of unattainable ambition and repression. Prominent commanders and nuclear scientists were targeted and the tower of hopes and dreams that had imposed years of sanctions, international isolation, poverty, and hunger on the people collapsed. Structural crises became apparent to everyone and the last remaining faithful and loyal forces of the regime, with sadness and regret, discovered the inefficiency and empty hands of the military that they had been calling for years and promising superiority and victory. The crisis of legitimacy in the midst of this field was raised and the world became aware, but the Iranian government, following its usual habit, resorted to violence, creating an atmosphere of terror and intimidation and taking advantage of its powerful weapons. In this way, the security system turned to prisons, where groups of citizens are always held captive and used as “mourning birds” and “

The government, however, was unable to convince the public and the virtual space that they were spies. According to Article 501 of the Islamic Penal Code (Punishments and Deterrents): “Anyone who deliberately and knowingly provides plans, secrets, documents, or decisions regarding the country’s domestic or foreign policies to individuals who do not have the authority to access them, or informs them of their contents, in a way that constitutes espionage, shall be sentenced to one to ten years of imprisonment, depending on the severity of the crime.” The convicts were sentenced to death, but often did not have job positions that would allow them to access confidential documents or information, which is a material element of the crime of espionage, namely transferring these to the enemy. Nevertheless, the judicial and security apparatus of the Iranian government not only referred to them as “spies,” but also called them “enemies” and “corruptors on earth.”

In addition, widespread suppression and mass arrests have been carried out under the pretext of a strange phenomenon called the “Law on Combating Hostile Actions by the Zionist Regime against Peace and Security”. This so-called law is not really a law, as all its components violate the rights, freedoms, and security of the people and promote lawlessness. For example, in Article 8 of this law, it is written in a way that any judge can convict anyone as an example of it: “Any action, such as security, military, political, cultural, media, propaganda, economic and financial assistance, directly or indirectly, in support or strengthening of the Zionist regime is prohibited. The offender shall be punished with up to five years of imprisonment.” This law does not define any clear boundaries or definitions of the crime. The term “indirect assistance” in this definition is not clear and it is not known what supporting and strengthening the Zionist regime means. This phenomenon did not end there, and the

Hannah Arendt argues in “Totalitarianism” that totalitarian regimes create a climate of fear and eliminate any form of opposition in order to maintain their power. These regimes neutralize any potential resistance by destroying individuality and creating a homogenous society. In this framework, political executions after the 12-day war, under the pretext of implementing the law of retaliation or corruption on earth, and the widespread detention of at least 21,000 people, aim to prevent any resistance to the government’s policies. According to official statements, 21,000 people have been arrested as suspects after the war. The charges brought against these individuals, along with the widespread arrests and propaganda efforts of the government, have created a climate of fear in the public and revived memories of the 1988 massacre of political prisoners. The source of this claim is an article by the Fars News Agency, which praised the 1988 executions as “successful” and called for their repetition. (1).

Hannah Arendt emphasizes that totalitarianism targets not only real opponents, but also the potential for opposition. (2) Reports of the detention of individuals who were simply arrested for protesting against the damages of war or criticizing crisis management support this view. These actions create fear and terror, pushing society towards passivity and eliminating the possibility of forming critical discourse.

The corruption of evil and the bureaucratization of violence.

The concept of “banality of evil” by Arendt, which was raised in “Eichmann in Jerusalem”, refers to crimes committed by ordinary individuals, not necessarily evil, within a bureaucratic system. (3) Arendt argues that these individuals, by blindly obeying orders and accepting the ideology of the regime, participate in these crimes. (3) Regarding the executions after the 12-day war, the judicial power of the Islamic Republic, judges, security officials, and government media – such as Fars News Agency – played a role in normalizing violence by justifying these executions as “necessary for national security” or a “successful historical experience”.

Arendt believes that in such systems, individuals are more focused on carrying out orders and accepting official narratives rather than critical thinking. (3) Judges who issue death sentences or officials who carry out these sentences likely see themselves as mere “employees” fulfilling their duties. This normalization of violence, as Arendt warns, is the most dangerous feature of totalitarian regimes, as it eliminates individual responsibility and turns crimes into a routine bureaucratic process. The unrestrained violence of the government, starting from detention and torture and ending in execution, is interpreted by Hannah Arendt’s theoretical framework. Arendt draws a clear line between power and violence, arguing that power comes from the support and consent of the people, while violence is used when a regime has lost its legitimacy. (4) The 12-day war has exposed the deficiencies, complacency, and structural corruption of the government and exacerbated the crisis of legitimacy. Public dissatisfaction with the government’s warmongering, irresponsible ideological interventions in other countries,

Arnt warns that the use of violence instead of power is a sign of fragility in totalitarian regimes. (4) Swift executions without fair trials, along with the detention of thousands, not only did not strengthen popular support, but rather isolated the government further and proved Arnt’s words that “violence, unlike power, cannot provide a strong and stable foundation for governance”.

Propaganda and the Dualism of Friend-Enemy.

Arendt emphasizes the role of propaganda in justifying oppressive actions in the origin of totalitarianism and believes that totalitarian regimes use propaganda to eliminate critical thinking and create obedience. (2) In Iran, government media tried to justify executions and arrests by creating a dichotomy of “friend-enemy” and labeling opponents as “traitors” or “agents of foreign enemies”. During the war, the concept of patriotism was revived and used by those who were not truly patriotic and did not limit their actions to their country, but rather those who were so immersed in political Islam that they considered the presence of the Islamic nation as their homeland, not their own country. This discourse, by labeling opponents as foreign threats, attempted to mobilize public opinion and suppress any criticism. Arendt argues that such propaganda, by simplifying reality and creating imaginary enemies, eliminates the possibility of public discourse. (2) In this regard, justifying executions under the pretext of “national security” or “defense of the

Political executions after the 12-day war between Iran and Israel, from the perspective of Hannah Arendt’s theory, are examples of mechanisms of suppression in a totalitarian system. These actions, carried out with vague accusations and without regard for fair trial principles, were an attempt to strengthen control through fear and elimination of opponents. (2) The concept of banality of evil shows how ordinary people in a bureaucratic system contribute to the implementation of violence. (3) Arendt’s distinction between power and violence also reveals the fragility of the government in using suppression instead of gaining popular legitimacy. (4) Propaganda, by normalizing these actions, helped to strengthen the totalitarian space. (2) However, as Arendt warns, relying on violence instead of power can lead to even greater instability; especially in a situation where the international community has condemned these actions. This analysis shows that political executions are not only a violation of human rights, but also signs of a deeper crisis in Iran

Notes:

1- Why should we repeat the experience of the executions of 67? Fars News Agency, 16 Tir 1404.

2- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Translated by Mehdi Tadini. Tehran: Parsa Publishing, 1396 (2017).

3- Arnt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Translated by Zahra Shams. Tehran: Borj Publishing, 1396.

4- Arnt, Hannah. Violence and Thoughts on Politics and Revolution. Translated by Ezatollah Fooladvand. Tehran: Khwarizmi Publications, 1358.

Tags

Fire extinguisher Marzieh Mohabbi Peace Line 172 Twelve-day war