Torture Memoirs in the Three Decades After the Revolution / Ali Kalai

The text cannot be translated as it is an image and not written in Farsi. Please provide the text in written form.![Ali-Kalei[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Ali-Kalei1.jpg)

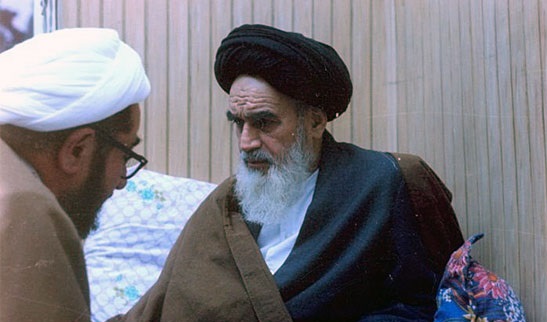

Ali Kalai

At midnight, he wakes up to the sound of rustling and incomprehensible noises. Cold sweat covers his body and fear takes over his entire being. He blinks his eyes twice to get used to the darkness of the night. He remembers what dream he was having. After months and years, the memories of those nights and days do not let him go. He falls asleep hoping that those days and nights will not haunt him anymore. But seeing them in his dreams tortures him. “Torture”; a word that perhaps should be written about.

The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment was adopted on December 10, 1984 and was implemented on June 26, 1987 by the General Assembly of the United Nations through Resolution 46/39, relying on the enforcement power of the convention. This global convention defines torture in Article 1 as “any act by which severe physical or mental pain or suffering is intentionally inflicted on a person for obtaining information or a confession from him or a third person.”

The statement is clear. Any behavior that causes suffering as explicitly mentioned in this article. However, sometimes those in power, authorities and oppressors seek justifications from the fact that it is a state of war or a special situation and that bombing may be possible, and torturing an individual and behaving based on torture with a suspect may lead to saving others. The same argument that led to the creation of Guantanamo after September 2001.

Furthermore, this convention does not authorize or justify the imposition or use of torture on any situation or individual in clauses two and three.

Materials and goods are completely clear and evident. Talking about ethical speeches of a moral philosopher and prescriptions of a religion is not the case. We are talking about a global convention agreed upon by nations after the traumatic experiences of two world wars and tragedies like Vietnam. The convention is popular during the Iran-Iraq war, at a time when Iranian prisoners are being tortured under the boots of the Iraqi regime’s intelligence. But it seems that these international laws should have been read much earlier; they don’t read them and sometimes even justify them years after the time of their commission. It was not long ago that Ahmad Farasti, one of the leaders of the Savak operations, was staring into the eyes of the audience and the camera on the BBC program, claiming that he did not know what torture was and saying that if someone is going to plant a bomb and we don’t know where it is, then we are justified in getting a confession from him. I wish someone was on that terrifying program to ask

When discussing a phenomenon of this global nature, one must either approach the discussion in a general manner and talk about overall concepts and situations, or if the intention is to focus on a specific topic, the discussion must directly address the designated subject. In the discussion of torture, let us not dwell on the experiences of other nations. Let us not just pass by, but rather let us pass through the realm that is our concern, the definition of our home, and the place of all our possessions, yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Torture in Iran also has a very long story. From political actions that are translated into punishment (and it was just yesterday in an era more than a hundred years ago) until today and until its yesterday. In the era of Iranian kings from the beginning of civilization. Its story in Iran is not a short one. But let’s also make a historical allocation and go to an era when the rulers in the era of modern humans, in the century of human civilization, wanted to rule. Their rule was not customary to do whatever they wanted to do in accordance with the customs of society, land and time. They spoke of goodness, justice and freedom. Of seeing the ruler and the other in front of the judge’s eyes. Of the kindness and kindness of their own rulers… But! Let’s take a step-by-step approach to three decades ago. That became our event.

More than three decades ago, a fundamental transformation took place in Iran. Under a regime where reading a thought-provoking book was considered a crime and the Joint Committee had prisons and SAVAK that burned people’s backs and ironed their skin. Vida Hajebi Tabrizi quotes a passage from Simin Daneshvar’s book “Judgment and Retribution” called “The Sleeping Beauty” about Fatemeh Amini. “I was peeling off the dead skin, as if I was cutting the threads of my heart. I was agitated and my hands were shaking. But my tears had dried up. Fatemeh was patient and didn’t say anything. She didn’t even flinch. One side of her body was paralyzed. I finished bandaging her wounds and reached her feet. The next day, I asked her: What did they use to burn you like this? She simply replied: They put me on an iron bed. The interrogator stood

The story is very clear. Tomorrow was supposed to come spring and we would be free and liberated. The devil was supposed to leave and an angel was supposed to come.

Revolution

The revolution happened and from the day after the revolution, instead of “Day of Mercy”, the “Day of Epic” began and the drums of resistance were beaten. It started from the rooftop of the Alavi school on the first night after the revolution and moved forward. However, on that day, few protested against the atrocities and there was no systematic structure of oppression. There were a few empty-headed individuals who followed Khomeini’s orders and scattered humans like autumn leaves on the ground and moved forward.

The process of events moved forward. We could write and speak about it from Bahman 57 to Khordad 60 for hours and pages. But let’s leave it for another time and reach a point where our topic, which is torture, was systematically implemented. And things got to a point where the deputy leader, in a short piece addressed to the leader, says, “It has been heard that you have said: ‘So-and-so [Mr. Montazeri] considers me [Mr. Khomeini] as the Shah and my information as the Savak. Of course, I do not consider Your Excellency as the Shah, but your information and prisons have made the Shah and Savak white. I say this with deep knowledge.” {Memoirs of Hossein Ali Montazeri – Volume 2, page 1212}

The decade of the sixties.

The prisoners of the 1960s, who were nicknamed the “Black Decade”, are many. Those who were released after the years 64 and 65, through the story of the Amnesty Committee, or those who were lucky enough to escape the summer 67 massacre, have told many stories. Let us now hear a story from the memories of Mr. Montazeri. In his memories, pages 522 to 525, he quotes Mr. Jafar Karimi, who was sent by Mr. Khomeini to investigate prison affairs, saying: “We went to the Hesarak (or Qazalhesar) prison near Mardeabad. There we saw a blanket and a black blanket in front of a room, and inside it was so dark that day and night could not be distinguished, and about 10 people were imprisoned there… We came across a girl who was being raped, they had tortured her so much that she had gone mad and they were

In those years, many released prisoners have spoken and written about it. The issue even went to the stage of forming a court called “Iran Tribunal” and the families of the victims of the 1980s were successful in condemning the Islamic Republic in two stages, “London” and “The Hague”.

Iraj Masdagi, one of the survivors of the 1967 massacre, recounts the physical tortures of that decade in his book “Neither Life, Nor Death”, which is a combination of memories and reports from prisons in the 60s of the Islamic Republic. In the first volume, he lists the titles of physical tortures of that decade: “Hitting and tortures such as hitting the head or genitals with a cable, kicking the tortured feet with boots, cutting off body parts with a cable, cutting off nails and fingers, hanging and tying hands in a squatting position, crucifying prisoners, hanging them from the ceiling by their hands and feet, “chicken kebab” which is tying up prisoners, extended cable hitting and similar methods – burning like hot iron, burning different parts of the body with cigarettes, burning different parts of the body with a lighter, even burning genitals with a gasoline stick, burning with an iron and electric stove and similar methods – beating like

Psychological tortures such as, imprisonment of the soul in relation to family, breaking the personality of the prisoner, artificial execution, forcing the prisoner to witness violent scenes, blindfolding and solitary confinement were also common practices.

But in this decade, prisoners were not released after going through the interrogation stages; whether they received a sentence and went to prison, or were sentenced to death, they were subjected to severe and brutal torture as long as they were either alive or in prison. Only a few examples of the tortures during those years were “keeping prisoners in very small spaces, sleep deprivation and standing for long periods, cages, residential units, coffins, and the infamous “Qas” pressure” that caused some prisoners to go insane. Even after years have passed, some still struggle to talk about and describe the torture they endured, with tears, stress, and heavy pressure accompanying them.

The families of prisoners in this era were not deprived of the blessings of the Islamic Republic system. The least they could do was to show some behavior after the massacre of sixty-seven of them and not show the place of their loved ones.

The tortures of the 1960s and the era of the establishment of the Islamic Republic, especially during the reign of the prosecutor Lajvardi, were both black and white. It was both about breaking and destroying the prisoner’s body and about breaking and destroying their spirit. However, an extreme level of violence prevailed in these tortures, which could sometimes be a source of anger and increase the prisoners’ morale in dealing with the torturer. In other words, that level of blatant violence often led to prisoners becoming angry and then increasing their resistance due to their anti-spirit and struggle for survival and life in prison.

Talk of the white torture began. We will deal with this term more in the future. It is better to first have a definition of it.

White torture

Roxandra Sseriano, the author of the book “Communism and Suppression in Romania: A History of National Fratricide”, refers to white torture as a form of psychological torture in her article “A Look at Political Torture in the Twentieth Century” published in a journal called “Studies in Religion and Ideologies” in 2006. She argues that white torture is not necessarily physical, but compared to targeted and effective violence, its psychological torment and cognitive pressure are more excruciating and agonizing. White torture creates sensory deprivation and isolation, causing the prisoner to lose their sense of self and identity in the long term.

The torture of the 1990s included both black and white forms, with the characteristic of having a higher level of violence. Even in its white torture space, the victim and the perpetrator could face each other and the perpetrator could be revealed.

In 1967, a massacre took place in which Reza Alijani, a journalist, named it the “Iranian Holocaust”. A great genocide was carried out and it was planned for the ruling government to have an easy time dealing with political opponents and dissenters for several years. In 1968, the founder of the regime and the one who gave the order for the 1967 massacre, along with all the other crimes of the 1960s, passed away and his life was surrendered to the Creator like all humans.

One decade later, the 70s decade.

In the 1970s, a new era of leadership and a new powerful president arrived. But in those early years, an incident occurred. The story of the 90-signature letter and the personal letters of national figures and patriotic Iranians to Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and the security crackdown on them foreshadowed new events. Events that later led to serial and political assassinations and severe suppression of opponents in the 1970s. Engineer Abdolali Bazargan, the son of Iran’s first prime minister after the victory of the revolution, who himself held positions in the revolutionary government, responded to the question of what happened to you briefly on those days, saying: “Out of the 25 people who were arrested, only four or five of us, including myself, were not physically tortured because of the famous 90-signature letter. But if we consider the 220 days of solitary confinement and the following six months in a closed room, with direct and

In the initial stages of this decade, it seems that breaking and, in the words of Hashemi Rafsanjani, the president at the time, reducing the number of prisoners or, as Engineer Abdolali Bazargan put it, breaking down personalities, is the main goal. Physical violence or black torture does not occur at the level of the first decade. Rather, this approach is completely targeted. After the massacre of 67, the protesting personalities must be broken down after the death of the founder of the system so that no voice is heard from anyone again.

This is an example of the systematic nature of torture in the Islamic Republic, with a fixed identity and variable forms.

Reforms, a fresh promise.

The years of reforms, however, bring a new hope. In Khordad 76, Mohammad Khatami is elected as the President and is expected to bring new words. The political assassinations of 77, however, change the atmosphere and the tragedies of Tir 78 mark a different story.

Many people are arrested following this event. Malous Radnia, also known as Maryam Shansi, who became one of the main suspects and confessed to the events on television, responded to the writer’s request to tell her story by saying that after consulting with her doctor, she faced the consequences of returning to that time and telling the events without permission. Because returning to those days could cause emotional harm and turmoil for her.

Ali Afshari, a member of the Central Council and political secretary of the Office of Consolidation of Unity, was the only student organization at the time that had become independent from the events of the 1970s and had to some extent returned to the nature of university and student independence. He has been one of the main actors in the events of those years. He was arrested after the Berlin Conference in Azar 1379 and this arrest was carried out through his televised confession.

In a letter addressed to Hashemi Shahroudi, the former head of the judiciary in 1384 (2005), Afshari writes about a week of continuous interrogation, sleeplessness, and standing against the wall with threats of various forms of torture due to the refusal of the interrogators to accept the charges of incitement and other similar cases. In the same letter, he also mentions other forms of torture and pressure, such as 328 days of solitary confinement, multiple sleepless nights, threats and staging of execution, spreading false news, deprivation of visitation and phone calls, and so on.

Interrogations and pressures during this period gradually shift from physical and physiological pressure to mental and psychological pressure. The apparent violence of these pressures, which could lead to anger and strengthen the prisoner’s resilience against the prison guard, decreases and precisely moves towards the main characteristic of white torture, which is the destruction of the prisoner’s personality and identity and turning them into a tool for carrying out the interrogator’s desires.

The 80s decade

This trend continues in the 80s and except for a period after Khordad 88 when the ruling political authority, out of fear of being completely removed, resorts to mental pressure and torture beyond limits – such as the case of Kahrizak – much more psychological pressure is exerted on detainees than physical pressure (at least in Tehran).

The writer himself has experienced the security detention centers of the Ministry of Intelligence of the Islamic Republic in Tehran in the years 2007 and 2009, and has personal observations of them. During this time, the level of physical abuse is minimized (not eliminated and in some cases heavy beatings are also applied), but psychological and emotional torture is elevated. Long periods of solitary confinement, lack of communication with family, transfer of prisoners to mental hospitals under the pretext of mental problems with the aim of harassing prisoners and placing them among mentally ill patients, giving false news about the situation of prisoners’ families who have emotional attachment to them, in conditions where prisoners do not have access to real resources related to their families outside, threats of sexual assault on prisoners or insults to their families, pressure on some prisoners’ spouses to divorce even with shameless offers from interrogators to harass prisoners inside the prison, and many other cases that report psychological and emotional torture of prisoners, which is much more than their physical and

One important point to mention here is necessary. The behavior of detaining institutions in Tehran towards political activists may have changed, but in smaller cities it seems to be stuck in the same pattern as one or even two decades ago. Farzad Kamangar, a teacher and human rights activist who was executed in Ordibehesht month of 1389, listed some of these behaviors in his diary. Kamangar talks about being electrocuted and threatened with sexual assault with a baton, and then being forced to play football with him in the Kermanshah intelligence detention center, as well as being shocked on sensitive body parts and being whipped. This late human rights activist also recalls the infamous torture method known as “whipping” in the Sanandaj detention center that he endured.

In addition, torture was not only the fate of political prisoners. Evin prison before 1988 was a detention center for those who were arrested in the program known as “fighting against hooligans and thugs.” There are many accounts, but only seeing a strong person suffering from weight loss and emaciation after being released speaks volumes about the tragedy that occurred.

Repeating a conversation from more than two decades ago.

Here, it seems necessary to quote only one of the political prisoners after the 1988 elections, who himself was a revolutionary in 1357 and for years was a supporter of the Islamic Republic system. Abolfazl Ghadiani, a senior member of the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization in Azar 1391, in response to the behavior of Dr. Ali Reza Rajaei’s interrogator, a member of the National Religious Activists Council in Iran who had asked Rajaei’s wife for a divorce, in a letter from Band 350 of Evin Prison addressed to the head of the judiciary, explicitly repeats Ayatollah Montazeri’s words in the middle of the 1960s and says, “The sins of your interrogators have whitened the faces of the torturers of the Shah’s Savak.”

With a brief look at the history of these three decades in the Islamic Republic system in the field of torture, it becomes clear that the trend of behavior based on torture in the Islamic Republic begins with the prevalence of black torture, along with white torture, in the central prisons and detention centers. As black torture fades in these facilities, white torture takes its place. In fact, the security systems of the Islamic Republic, by learning from the history and security systems of various countries around the world, try to turn the prisoner into a tool for expressing their demands by breaking their spirit and emptying them of themselves. The prisoner becomes empty and alienated, and eventually becomes a repeater of the interrogator’s demands. In many cases, the prisoner even finds their interrogator to be their best friend and even falls in love with them, all with the least amount of beating and violence. In fact, the established security system gains the most profit with the least cost, and also renders the prisoner ineffective after

But the words of Farzad Kamangar and many like him reveal that the behaviors of the 60s and 70s are still prevalent in the counties, especially in the border counties. A duality that seems to believe that no one sees the counties and can do anything without being noticed.

The history of torture in Iran after the revolution is a painful one. Both types of torture have taken and continue to take many victims in different years. The above text is only a step towards opening a door to identify the various forms of torture in these years and perhaps a step towards exposing and moving towards a time where we no longer witness torture in Iran. Until that day, we must stand tall against it and do everything in our power. These are the human duties that make us more human. We must do everything we can.

Created By: Ali Kalaei

Created By: Ali KalaeiTags

Abdul Ali Bazaar Ali Afshari Ali Kala'i Farzad Kamangar Magazine number 52 Maryam Shansi Monthly Peace Line Magazine Torture 2 White torture شکنجه ماهنامه خط صلح